SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

Nontraumatic convexal subarachnoid hemorrhage (cSAH)

Updated on 18/02/2024, published on 06/04/2021

Definition

- non-traumatic spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage at the convexity (non-traumatic convexal SAH – cSAH) is defined as a collection of blood in one or more adjacent sulci, in the absence of SAH in another localization

- it is relatively rare, but the etiological DDx is quite broad

- in patients ≤ 60 years of age, the most common cause is Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome [Kumar, 2010]

- in patients > 60 years of age, the most common cause is Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA)

Clinical presentation

- severe headache typical for classic SAH is usually not present [Beitzke, 2011]

- headaches are generally present in cerebral venous thrombosis, RCVS, and PRES

- transient focal symptoms (paresthesias, paresis) are frequent, which leads to suspicion of stroke/TIA (cSAH belongs to stroke mimics)

- the etiopathogenesis of transient symptoms is unclear; cortical spreading depression triggered by blood in the SA space is considered [Beitzke, 2011]

Diagnostic evaluation

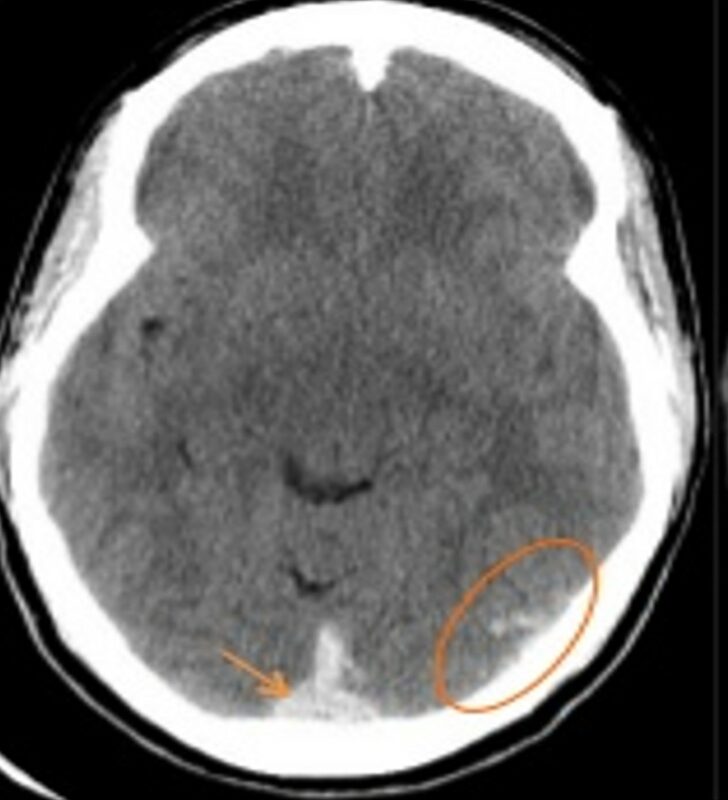

Computed tomography

- the primary diagnostic method

- a finding of sulcal hyperdensity leads to the indication of CTA (both arterial and venous phases)

- CT sensitivity is approx. 90% in the acute phase but decreases quickly with time (the lesion becomes isodense)

- given the wide DDx, it is advisable to add an MRI

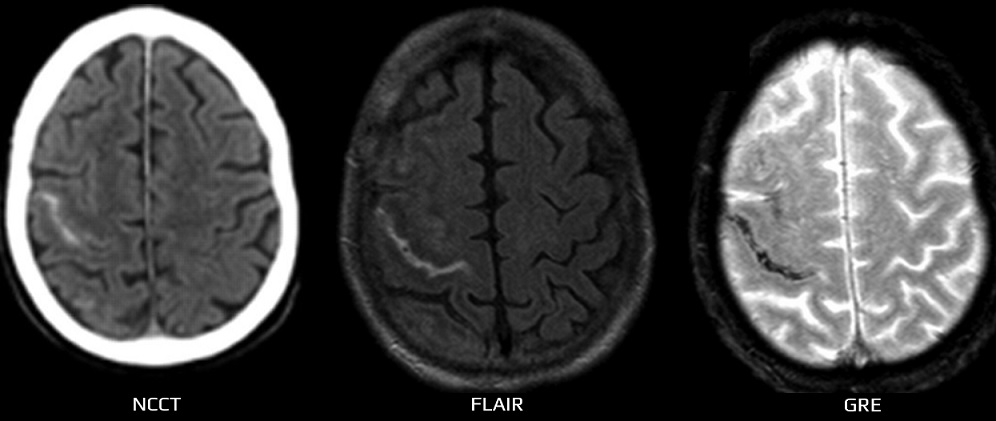

Magnetic resonance imaging

- perform the following sequences:

- FLAIR

- GRE or SWI

- DWI+ADC

- 3D TOF MRA + MR venography

- T1 and T1 C+

- FLAIR is highly sensitive to lesions in the subarachnoid space; cSAH appears as a hyperintense band

- in DDx of cSAH exclude:

- meningitis

- leptomeningeal metastases (LMM) and leptomeningeal melanosis

- post status epilepticus lesions

- previous contrast examination with gadolinium

- artifact

- FLAIR further reveals other typical structural changes in the parenchyma (e.g., PRES, etc.)

- GRE/SWI – confirms the hemorrhagic nature of sulcal hyperintensities and may also help in the detection of older hemorrhages or venous thrombosis

Etiology

- typical parenchymal abnormalities in ~ 50% of cases (edema, cortical infarction with/without a hemorrhagic component)

- cSAH has been described in thromboses of both dural sinuses and superficial veins

- it most likely results from cortical vein rupture due to venous hypertension

- MRI GRE helps detect hemorrhagic lesions and thrombosis itself, including smaller superficial veins (GRE directly displays the thrombus)

→ see here

- hemorrhages occur in approx. 5-17% of PRES cases:

- parenchymal hematoma

- minor hemorrhages

- cSAH

- AVMs can be a source of ICH with SAH; isolated cSAH is rare

- AVM is reliably detected on CTA

- superficially localized cavernous malformations can rarely be the source of cSAH

- extra-axial cavernous malformations are more vascularized and frequently show signs of bleeding on GRE/SWI

- extra-axial cavernous malformations are more vascularized and frequently show signs of bleeding on GRE/SWI

- CAA tends to occur in patients > 60 years of age [Beitzke, 2011]

- it is a degenerative angiopathy characterized by amyloid deposits in the walls of small and medium-sized vessels

- in addition to lobar hematomas and microbleeds, superficial hemosiderosis due to cSAH has also been described

- cSAH is most likely caused by the rupture of amyloid-attenuated leptomeningeal arteries

- clinically, there is no headache but rather focal symptoms, including epileptic seizures

- MRI GRE/SWI is optimal for hemorrhage detection

- RCVS typically presents with headache, variable neurological deficit, and reversible vascular changes

- headache is the most frequent and prominent symptom (often described as a “thunderclap” headache)

- detection of vascular abnormalities on CTA/MRA/TCCD is essential for diagnosis

- MRI shows parenchymal lesions, including cSAH

- the diagnosis is confirmed by the regression of vascular changes within three months

| RCVS |

PACNS |

|

| gender | F > M | M > F |

| onset | sudden onset |

gradual |

| course | monophasic |

chronic with fluctuations or fulminant |

| CSF | commonly normal |

pathologic finding |

| vascular imaging |

always a pathological finding with severe vasospasms resolution within a few weeks (< 3 months) |

negative in up to 50% of cases |

| parenchymal imaging |

usually normal ICH, SAH, or edema (similar to PRES) |

multiple ischemic lesions possible leptomeningeal enhancement |

| vessel wall imaging (T1C+ dark or black blood high-res images) |

negative |

positive [Obusez, 2014] [Mandell, 2012] |

- cSAH can be caused by the rupture of an infectious aneurysm (meningitis, endocarditis) or due to focal arteritis

- rarely, cSAH has been described as a consequence of abscess (again due to focal arteritis)

- clinical presentation: headache, general signs of infection (anorexia, fatigue, fever, etc.), or focal signs (caused by the mass effect of an abscess or ischemia and microhemorrhage)

- typical for Moyamoya disease or moyamoya syndrome is intraparenchymal or intraventricular bleeding

- cSAH is rare, most likely due to a rupture of dilated cortical arterioles

- a typical angiographic findings confirm the diagnosis

- in cases of hemodynamically significant extra- or intracranial stenosis, collateral circulation becomes involved

- the rupture of a dilated, congested pial artery may lead to cSAH (Hacein-Bey, 2014)

- FLAIR imaging shows serpiginous hyperintense structures, similar to the “ivy sign” described in moyamoya patients

- cSAH due to malignancy can be provoked by coagulopathy, venous thrombosis, PRES, or RCVS (potential side effect of chemotherapy)

- leptomeningeal metastases are a major consideration in DDx of cSAH

- both conditions share similar findings on CT and FLAIR imaging

- a sudden headache favors the diagnosis of SAH; however, it is often missing in cSAH

- leptomeningeal dissemination is characterized by a gradual development of cranial nerves paresis and postcontrast enhancement of the meninges (on T1 or FLAIR)

- in the subacute stage, cSAH appears hypointense on GRE

Differential diagnosis

- traumatic SAH

- history of trauma

- usually, a more significant extent of SAH in imaging methods

- concurrent contusions, sometimes only seen on a follow-up CT scan

- skull bone trauma is visible in the bone window

- cortical laminar necrosis

- associated with hyperintense lesions on MR DWI

- leptomeningeal metastases