ADD-ONS / OTHER VASCULAR DISORDERS

Spinal cord vascular disorders

Updated on 24/05/2024, published on 14/07/2023

Spinal cord vascular disorders usually present as neurologic emergencies and cause significant morbidity. Vascular causes include infarction, hemorrhage, and manifestation of various malformations. In the case of sudden lower limb paraparesis or tetraparesis, urgent imaging studies are critical to identify the underlying potentially treatable cause (tumor, herniation, epidural hemorrhage, etc.). Urgent diagnosis and appropriate treatment can significantly impact the patient’s outcome and prevent further neurological damage.

Diagnostic evaluation

- the choice of imaging modality is determined by the patient’s clinical condition, the urgency of the situation, and available resources

- MRI of the spinal cord

- preferred baseline imaging, best for identifying various etiologies (vascular disorder, compression, tumor, syringomyelia, etc.)

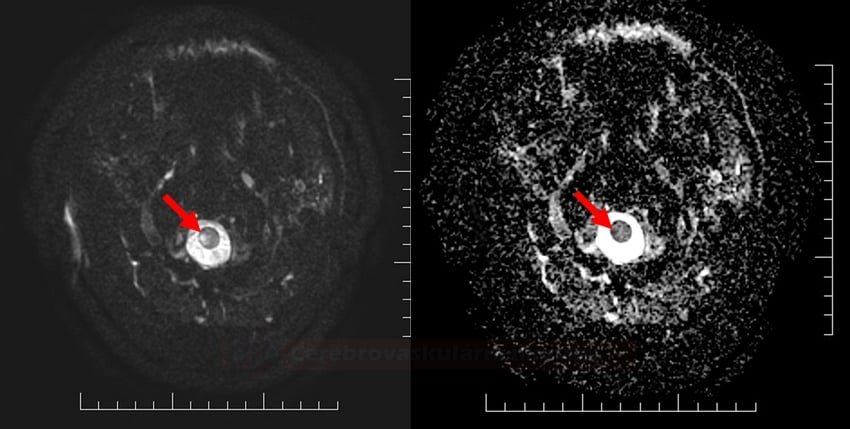

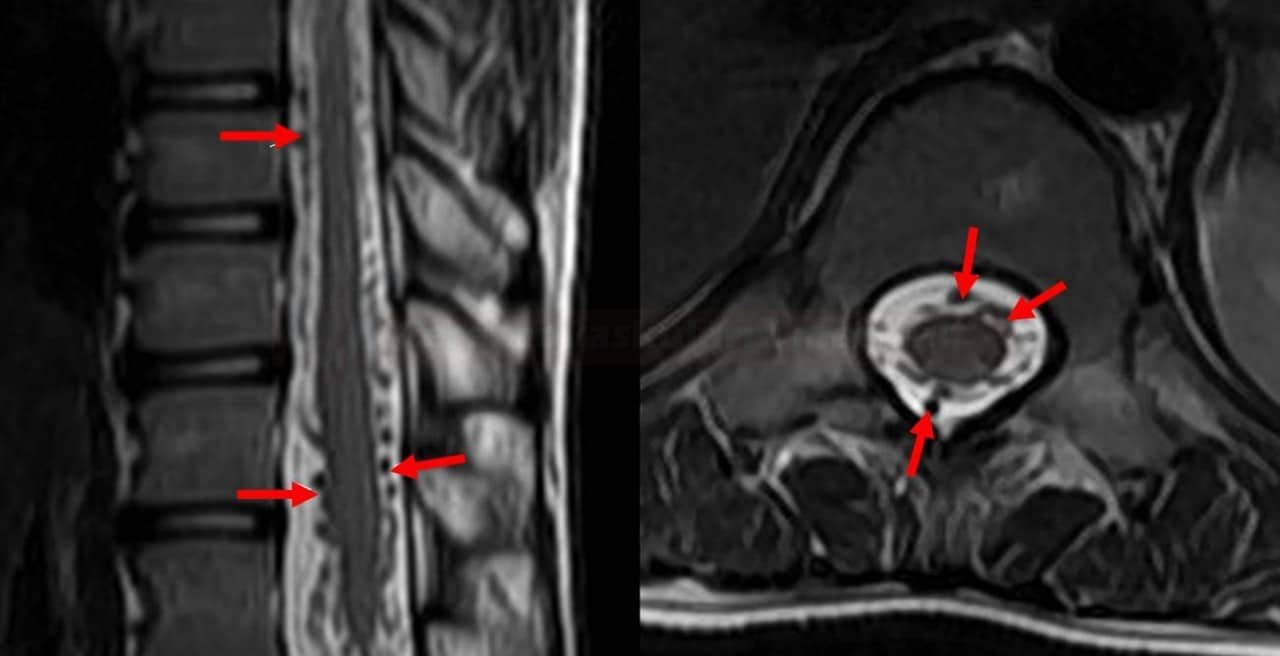

- acute spinal cord infarcts can be demonstrated on DWI

- less sensitive compared to brain lesions

- subacute ischemia (hyperintense lesion) is also seen on T2 and FLAIR

- always look for an associated infarct in the vertebral body

- the lesion may show some enhancement in the subacute phase

- MRI + MRA may help detect potential sources of bleeding (angioma, cavernoma, AVM)

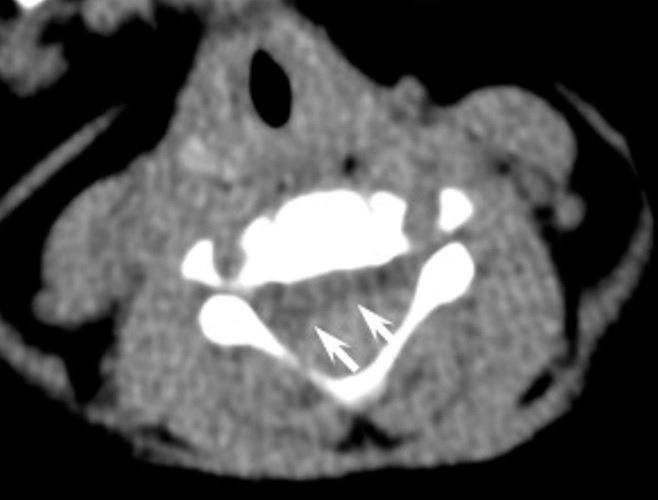

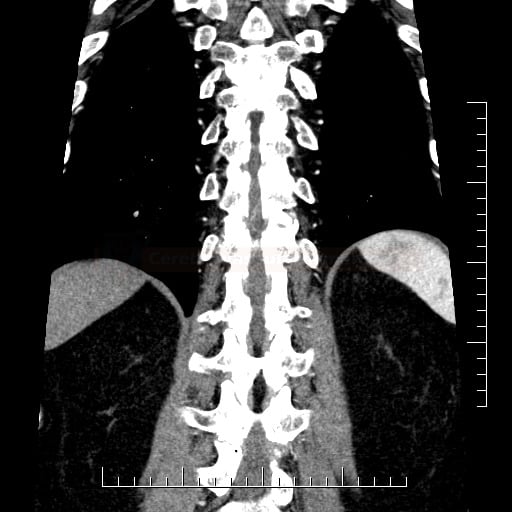

- spiral spinal CT + CT angiography

- CT excludes acute bleeding, trauma, and masses compressing the spinal cord; CT is less sensitive compared to MRI

- CTA excludes vertebral and aortic dissection or other relevant vascular pathology (e.g., occluded spinal artery, thrombosed aneurysm, massive atherosclerosis, malformation, fistulas, aneurysm, etc.)

- spinal DSA

- laboratory tests

- CSF analysis (if myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or MS are suspected)

- vasculitis tests

- tumor markers

- inflammatory markers

- thrombophilia tests

- basic inflammatory parameters

- ↑CRP

- ↑ESR

- blood tests for autoimmune diseases

- complement complex (lupus)

- p-ANCA, c-ANCA

- granulomatosis with polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, inflammatory bowel disease

- anti-dsDNA (SLE)

- ANA antibodies (SLE)

- most commonly used to diagnose lupus; these antibodies can sometimes also signal other systemic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, or Sjögren’s syndrome

- ENA panel (Extractable Nuclear Antigen)

- anti-Sm

- anti-RNP

- anti-SSA, anti- SSB (Sjögren Syndrome)

- ani-Scl-70 (scleroderma)

- anti-Jo-1

- antiphospholipid antibodies (SLE)

- LA

- ACLA

- anti-β2-glycoprotein I (anti-β2GPI)

- RF (rheumatoid factor)

- used to diagnose rheumatoid arthritis

- normal ranges: < 15 IU/mL, < 1:80 for titer levels

- routine blood tests

- basic metabolic panel

- to assess problems with the pancreas, liver, heart, or kidneys

- complete blood count (CBC)

- normochromic anemia, leukocytosis, eosinophilia

- coagulation studies

- basic metabolic panel

- CSF examination

- abnormal in up to 95%

- pleocytosis (less commonly mild mononuclear pleocytosis)

- proteinorhachia (~50-80%)

- oligoclonal bands (OCB); positive in (~50% of cases

- consider testing for autoimmune and paraneoplastic encephalitis antibodies

- basic infectious disease screening (Lyme disease, herpes viruses, HIV, syphilis)

The normal ESR ranges

- 0-15 mm/h for men < 50

- 0-20 mm/h for men > 50

- 0-20 mm/h for women <50

- 0-30 mm/h for women > 50

- 0-10 mm/h for children

- 0-2 mm/h for infants

CRP ranges

- < 0.3 mg/dL – normal, which is the level for most healthy adults

- 0.3-1 mg/dL – normal or mild elevation can be seen with obesity, pregnancy, depression, diabetes, common cold, gingivitis, periodontitis, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and genetic polymorphisms

- 1-10 mg/dL – moderate elevation indicates systemic inflammation, such as in the case of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or other autoimmune diseases, malignancy, myocardial infarction, pancreatitis, and bronchitis

- > 10.0 mg/dL – marked elevation signals acute bacterial infection, viral infection, systemic vasculitis, and major trauma

- > 50.0 mg/dL -severe elevation may be caused by acute bacterial infections

Sampling for hypercoagulable states must be performed before starting anticoagulation therapy, otherwise, the results are unreliable (not related to genetics). Many tests are influenced by acute phase reactants, diseases, and drugs. It is advisable to verify the disorder by sampling at a non-acute stage (2-3 months apart). Up to 75% of disorders are not confirmed on follow-up examination (Bushnell, 2001]

Spinal cord syndromes

- most common vascular spinal syndrome

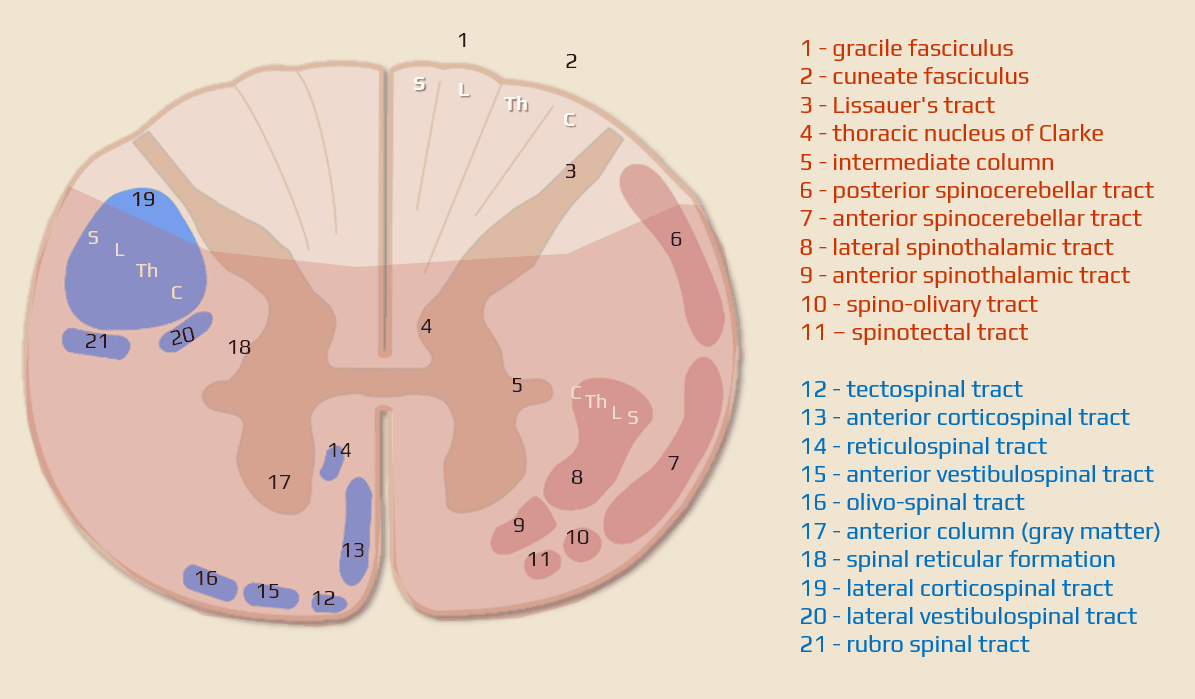

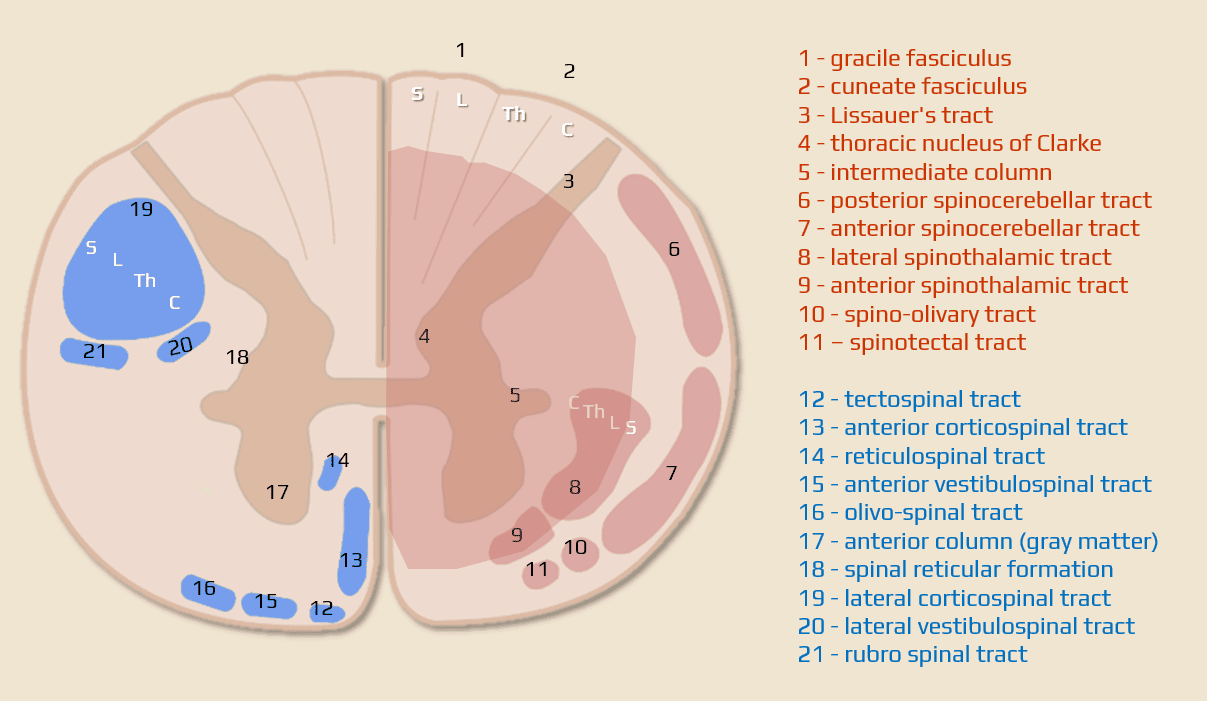

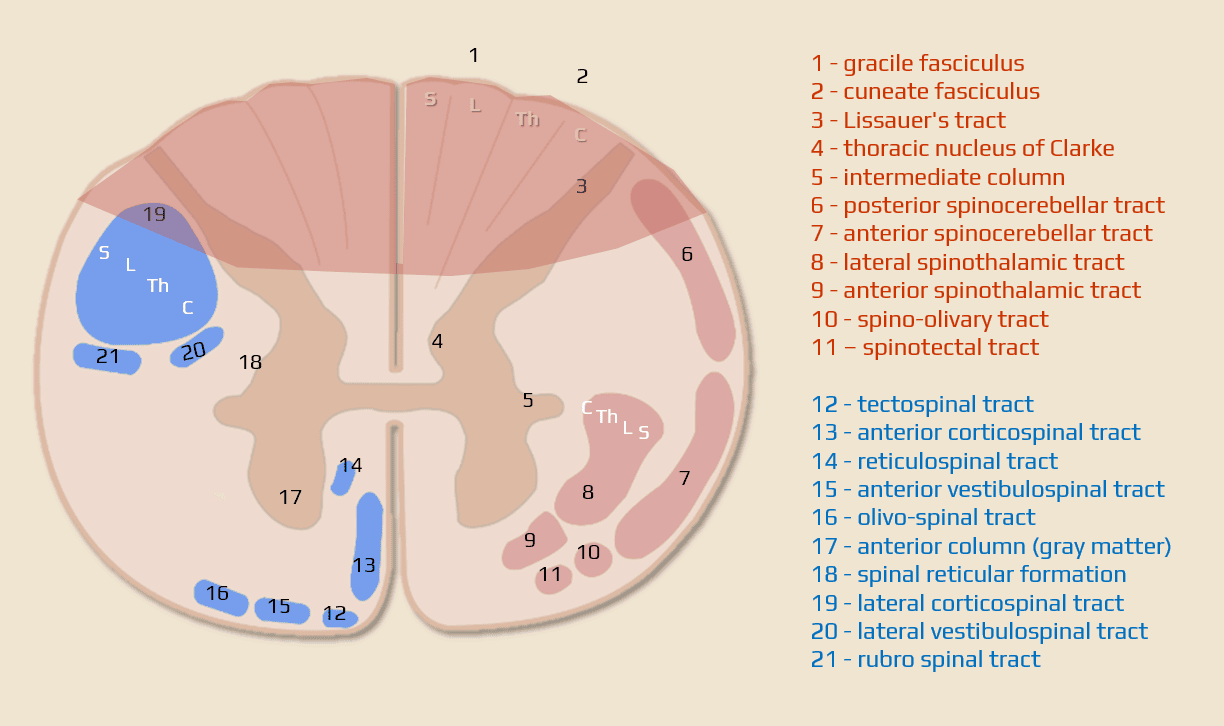

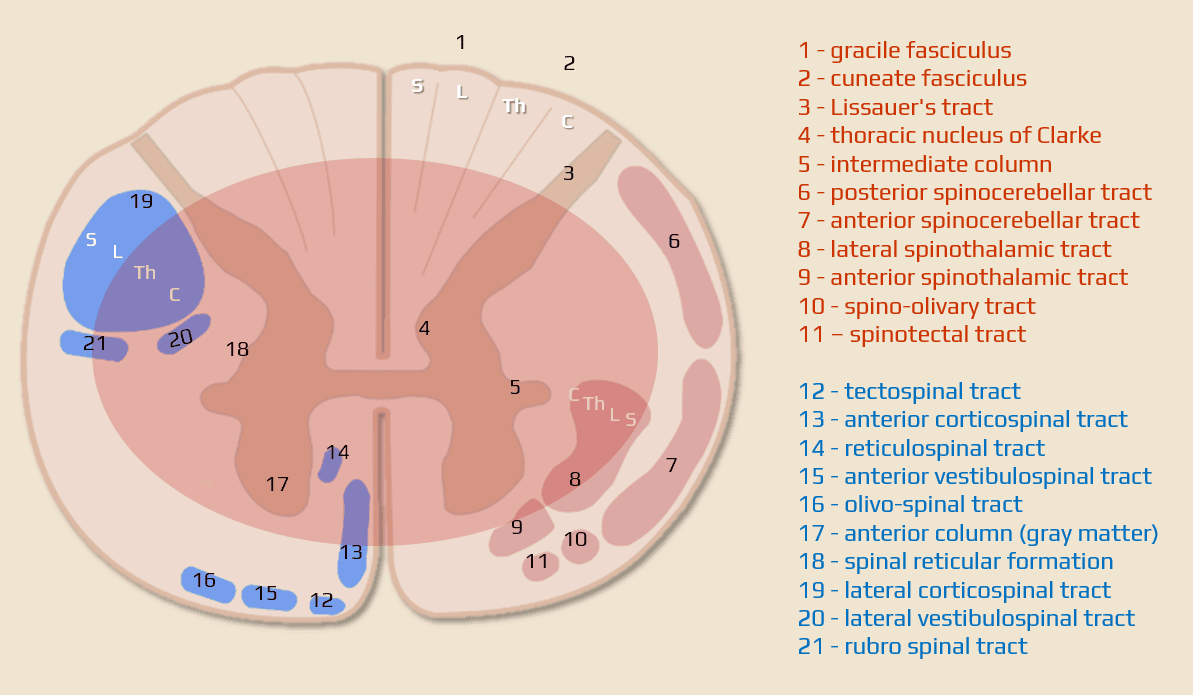

- affects the anterior 2/3 of the spinal cord, often multiple segments (see vascular supply)

- a typical warning sign is back pain

- symptoms:

- bilateral paresis (paraparesis or quadriparesis (corticospinal tract)

- autonomic dysfunction, sphincter problems

- impaired pain and temperature sensation (spinothalamic tract) with preserved deep sensation (dissociated disorder)

- etiology

- primary vascular (incl. malformation, stenosis) and circulatory (hypotension) disorders

- other causes may directly affect the spinal cord with/without artery compression

- syringomyelia

- degenerative spine disease/disc herniation

- hyperextension injuries (e.g., whiplash)

- radiation myelopathy

- HTLV-1

- primary vascular (incl. malformation, stenosis) and circulatory (hypotension) disorders

- also known as sulcal artery syndrome

- sulcal (central or sulco-commissural) arteries are perforating branches of the anterior spinal artery, which perfuse the anterior two-thirds of the spinal hemicord

- sulcal (central or sulco-commissural) arteries are perforating branches of the anterior spinal artery, which perfuse the anterior two-thirds of the spinal hemicord

- infarction of one half of the spinal cord (vascular Brown-Séquard syndrome)

- ipsilateral

- loss of all sensation at the level of the lesion

- loss of proprioception, vibration, and tactile discrimination below the level of the lesion (posterior column)

- flaccid paresis at lesion level (lower motor neurons)

- spastic paralysis below lesion level (corticospinal tracts)

- Horner´s syndrome occurs in lesions above T1 due to damage to ipsilateral sympathetic fibers (the oculosympathetic pathway)

-

contralateral

- loss of pain, temperature, and non-discriminative touch (crude touch) sensation below the lesion (interrupted spinothalamic tract)

- ipsilateral

- etiology:

- spinal cord infarction is very rare (Win,2020)

- knife/bullet injury

- multiple sclerosis

- spinal cord infarction is very rare (Win,2020)

- incomplete spinal cord injury affecting the central portion of the spinal cord

- bilaterally impaired thermalgesic sensation below the level of the injury (lesion of the decussating fibers of lateral spinothalamic tracts)

- quadriparesis – weakness can vary in severity and is often greater in the arms than in the legs

- bladder dysfunction

- “sacral sparing”

- intact toe flexion

- normal rectal tone

- intact perianal sensation

- recovery is usually not always complete, and residual impairments may persist

- etiology: spinal ischemia, syringomyelia, intramedullary tumors, cervical spondylotic myelopathy, trauma hyperextension injury, central canal ependymoma

- rarely of vascular origin

- affects the entire spinal cord with a complete loss of motor and sensory modalities below the level involved (including sphincter function)

- painful, rapid but not apoplectic onset (within hours to days)

- higher lesions are associated with spinal shock and autonomic dysfunction

- priapism is a sign of complete lesion

- sacral sparing (intact great toe flexor function, perianal sensation, rectal motor function) excludes complete transsection

- small ischemic lesions caused by lipohyalinosis of perforating arterioles

- may present with an isolated motor or sensory deficit, depending on which structure is involved

- subacute partial transverse myelopathy with back, abdominal, and lower limb pain

- caused by thrombosis or thrombophlebitis of the draining veins

Differential diagnosis

- nonvascular spinal cord lesions

- disc herniation with myelopathy with/without radiculopathy

- tumor of the spinal cord or its surroundings, especially epidural metastases

- abscess

- myelitis

- multiple sclerosis

- trauma or iatrogenic spinal cord injury

- radiation-induced myelopathy

- brain lesions

- bilateral infarcts in the ACA territory with paraparesis (usually in the context of variant ACA arrangement – azygos artery, etc. → see here)

- parasagittal tumors

- PNS lesions (e.g., polyradiculoneuritis) – difficult to differentiate in the acute phase

Classification

|

Spinal cord ischemia

|

Etiology

Arterial infarct

- atherosclerosis (aorta, radicular arteries, or involvement of spinal arteries and arterioles)

- vasculitis

- noninfectious (Takayasu, PAN)

- infectious (lues, herpes zoster, Lyme disease, tuberculosis, HIV)

- aortic surgery

- spontaneous aortic dissection (⇒ hypoperfusion)

- vertebral artery lesion

- dissection [Takahashi, 2012]

- atherothrombosis/thromboembolism

- external compression (often with associated cervical myelopathy)

- dissection [Takahashi, 2012]

- embolization

- spontaneous

- cardioembolism

- fibrocartilaginous embolism (FCE) – about 5% (posttraumatic migration of nucleus pulposus material into nearby arteries) (Lišková, 2018) [Abdelrazek 2015]

- air embolism

- iatrogenic

- thromboembolism or embolization of plaque masses caused by an intravascular catheter manipulation

- embolization material that traveled outside the target vessel [Cloft, 1999]

- spontaneous

- “surfer’s” myelopathy – prolonged prone position with spinal hyperextension ⇒ FCE, watershed infarcts, mechanical arteriolar damage [Choi, 2018]

- hypoperfusion – usually mid-thoracic segment affected

- heart failure

- hypovolemia (absolute or relative)

- others

- intravascular tumor invasion

- reaction of blood vessels to drugs, contrast media, etc.

Venous infarct

- course tends to be subacute

- hemorrhagic infarction is common

- patients with sepsis or malignancy are at increased risk

- etiology

- coagulopathy (congenital, acquired)

- AVM (blood stagnation with increased intravenous pressure)

- compression of veins (e.g., in spinal stenosis)

Clinical presentation

Intermittent spinal claudications

- recurrent, reversible ischemic symptoms; intermittent symptoms may eventually lead to permanent disability

- paraparesis, hypestesia and dysestesia

- involvement of the cervical segments may provoke sudden falls (drop attack)

- involvement of lumbar segments causes spinal claudications (leg weakness on exertion that disappears at rest)

- symptoms may be exacerbated or aggravated by hypotension (heart failure, anemia, etc.)

- AV malformations and AV dural shunts can also lead to intermittent paraparesis during exercise

- “flow diversion” into the bones may occur in morbus Paget

Spinal cord infarct

- clinical presentation is variable and depends on the level and extent (craniocaudal and transverse) of the ischemic lesion

- the middle and lower thoracic segments are most commonly affected

- spinal cord lesions can be divided into several syndromes based on the transverse extent of the lesion (see above)

- the anterior spinal artery territory is most commonly affected

- vascular lesions rarely cause complete transverse lesion (compared to trauma or myelitis)

- pain is frequent at the onset (in 80% of cases), followed by sensory and motor deficits; high cervical lesions carry a risk of respiratory disturbances

Management

- depends on the etiology; acute general therapy and secondary prevention are the same as with brain infarcts

- some specific procedures:

- treatment of potential malformation causing ischemia

- immunosuppression for vasculitis (rare cause)

- hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for air embolism

- lumbar drainage in ischemia after aortic surgery (lower CSF pressure ⇒ better arteriolar perfusion)

- skincare and management of sphincter dysfunction

Intravenous thrombolysis

Intraspinal hemorrhage

|

Spinal A-V malformations

|

- spinal arteriovenous shunt or malformation is a congenital disorder

- shunts are mostly located in the lower lumbar region and can be classified as intramedullary and extramedullary (most common)

- males are significantly more often affected than females

Classification of spinal cord vascular malformations

- dural arteriovenous fistula (DAVF)

- intradural

- extradural

- arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

- intradural (intramedullary x extramedullary)

- extradural

- cavernous malformation

- spinal aneurysm

Etiopathogenesis

|

Clinical presentation

- usually sudden (bleeding) or subacute myelopathy (ischemia or repeated microhemorrhages; Foix-Alajouanine syndrome)

- symptoms may correspond to a complete transverse lesion or some partial medullary syndrome

- the course may be fluctuating with more or less complete remissions

- symptoms usually occur between the 2nd and 5th decade of life

- most often localized in the Th-L segments

Diagnostic evaluation

- spinal MRI

- allows direct visualization of AVM (dilated vessels +/- nidus)

- T1 and T2 show flow voids from high-flow feeding vessels

- may show concurrent ischemia with cytotoxic edema; GRE/SWI sequences demonstrate even subtle bleeding

- CT – is better for showing recent bleeding

- spinal angiography (DSA/CTA)

- pathological vascularisation is almost always detectable

- AVM may be fed from the upper thoracic to sacral areas without spatial relationship to the clinical level

Therapy

- embolization

- surgical procedure – resection of a small superficial AVM

- combination of endovascular and surgical treatment

Prognosis

- prognosis is poor in cases where the malformation has caused extensive ischemia or bleeding

- wherever symptoms progress, e.g., in cases of fluctuating symptomatology or where spastic paraparesis occurs, surgical intervention should be performed before irreversible spinal cord damage occurs