ISCHEMIC STROKE / CLASSIFICATION AND ETIOPATOGENESIS

Vasculitis

David Goldemund M.D.

Updated on 02/03/2024, published on 24/05/2023

- connective tissue disorders and vasculitides are a heterogeneous group of diseases that may have various manifestations, including stroke

- vasculitis is characterized by inflammation of the walls of blood vessels and may affect vessels of any size

- it is a relatively rare cause of stroke (~ <3% of strokes in patients < 50 years of age [Ferro, 1998]

- routine testing in an unselected group of patients with ischemic stroke is therefore not useful

- in cases where the stroke is the initial symptom of the disease, such as in PACNS, diagnosis can be challenging despite extensive investigation, including CSF analysis and brain biopsy

- vasculitis may cause:

- stenosis/occlusion

- development of mural thrombosis with potential distal embolization

- artery rupture with bleeding (ICH, SAH)

- probably the most relevant disorders related to stroke neurology are:

Etiopatogenesis

Etiopatogenesis

|

Pathogenetic mechanisms in vasculitides

|

| I. Immune-mediated |

|

| II. Infection, physical or chemical injury (toxins, drugs, medication) |

|

Classification

Classification

- there are various classifications based on different aspects of the pathological process

- the following list of vasculitides is not complete; attention is given primarily to those that may affect the cerebral arteries

Classification based on the diameter of the affected vessel

| Classification based on the size of most affected vessels (Names for vasculitides adopted by the 2012 International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Vasculitides) |

| Large arteries (aorta and its main branches, including the intracranial ICA segment) |

|

| Medium-sized arteries (major organ arteries, arteries forming the circle of Willis) |

|

| Small arteries |

|

Primary and secondary vasculitis

|

I. Primary vasculitides

|

|

|

II. Secondary vasculitides

|

|

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation

- general symptoms (often absent in CNS vasculitides)

- weight loss, fever, fatigue, lack of appetite, increased sweating

- arthralgia, myalgia

- nervous system

- CNS

- headache

- epileptic seizures

- encephalopathy, stroke-like episodes

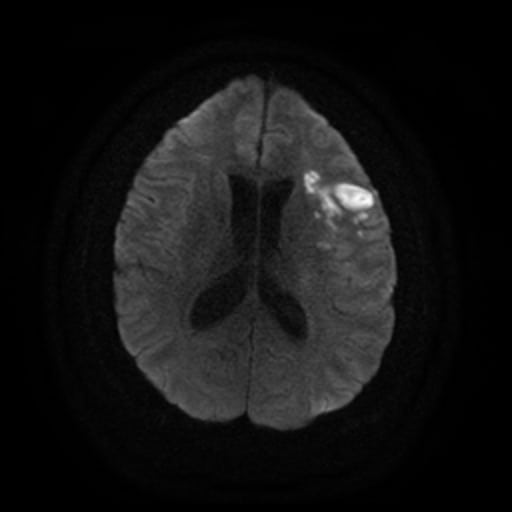

- stroke

- PNS

- polyneuropathy, mononeuropathy

- CNS

- lungs

- hemoptysis, cough, dyspnoea, asthma, lung infiltrates

- ENT

- sinusitis, otitis, deafness

- skin:

- purpura, pyoderma, necrosis

- eye:

- uveitis, iridocyclitis, episcleritis

- kidneys:

- renal hypertense

- proteinuria

- erythrocyturia

- renal failure

| Course | Signs and symptoms of CNS involvement |

|

acute/subacute

subacute

relapsing-remitting |

headache

|

|

epileptic seizures

|

|

|

stroke-like episodes

|

|

|

ischemic stroke, IC bleeding

|

|

|

encephalopathy

|

|

|

extrapyramidal disorders (chorea, myoclonus)

|

|

|

optic nerve disorders

|

|

|

cranial neuropathies

|

Diagnostic evaluation

Diagnostic evaluation

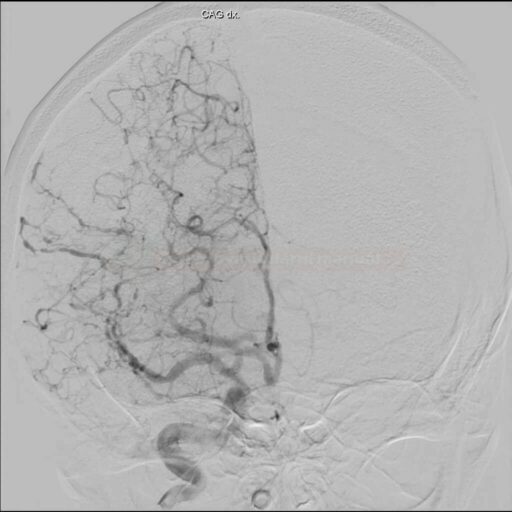

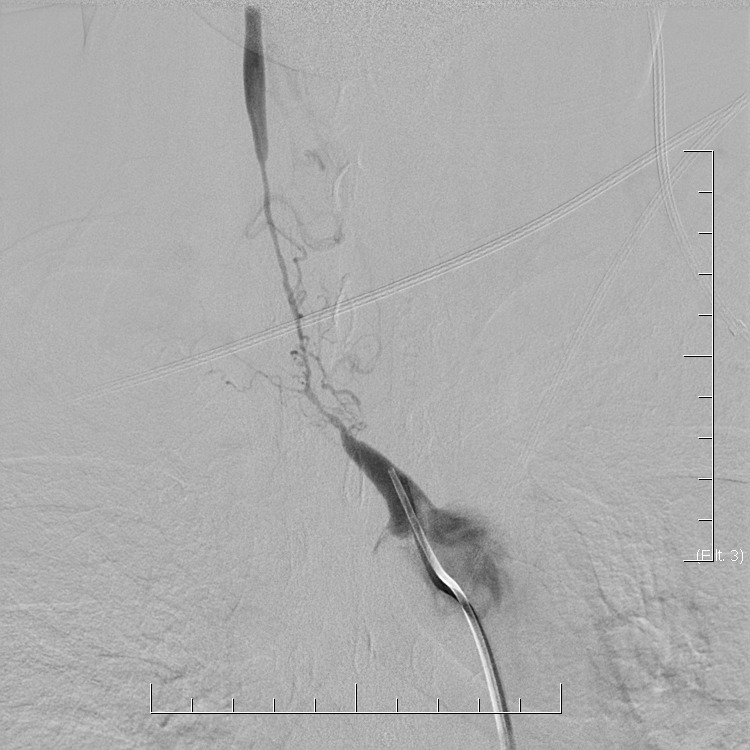

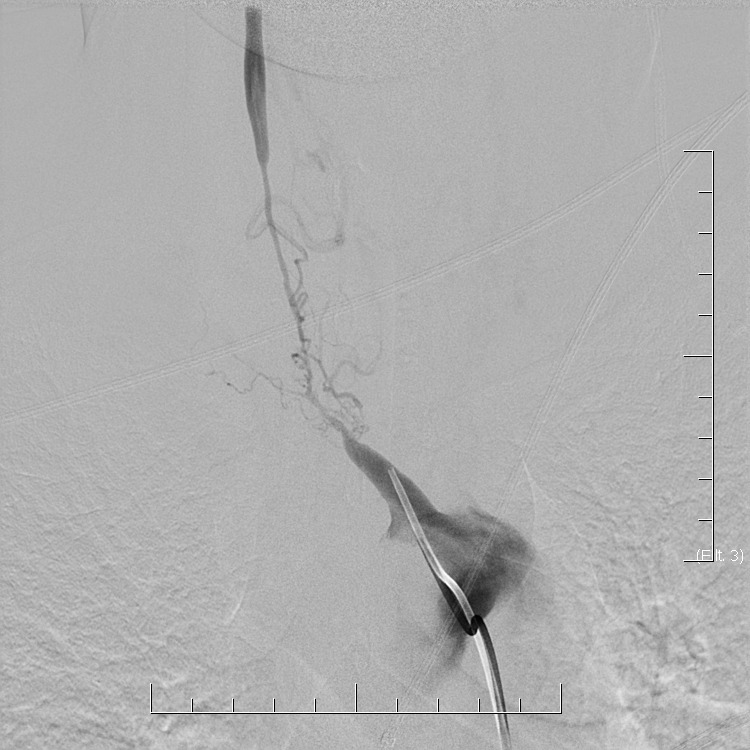

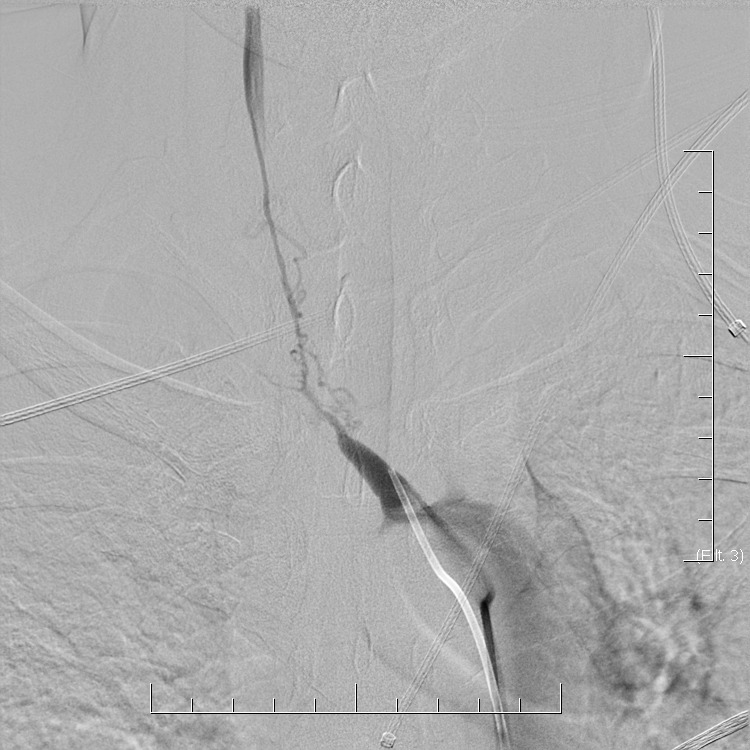

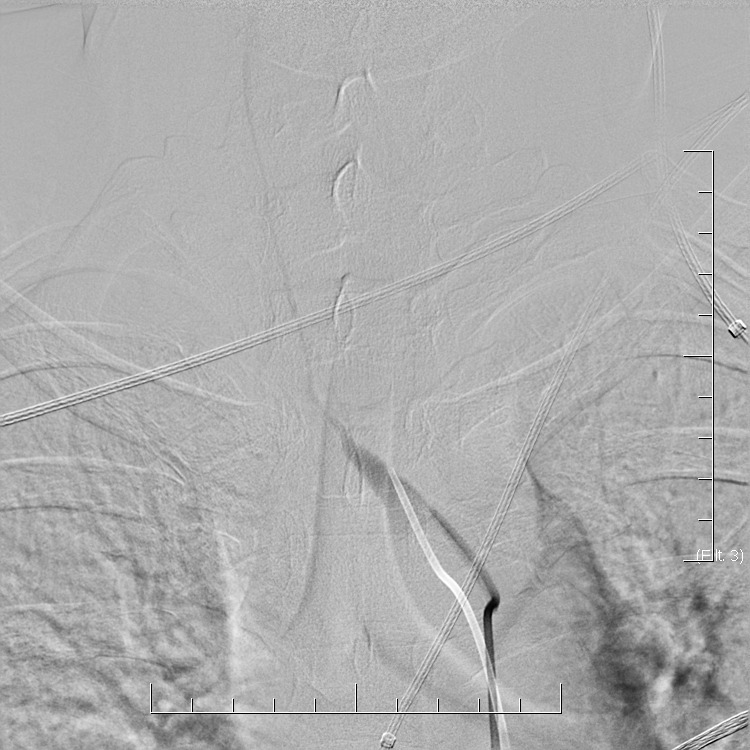

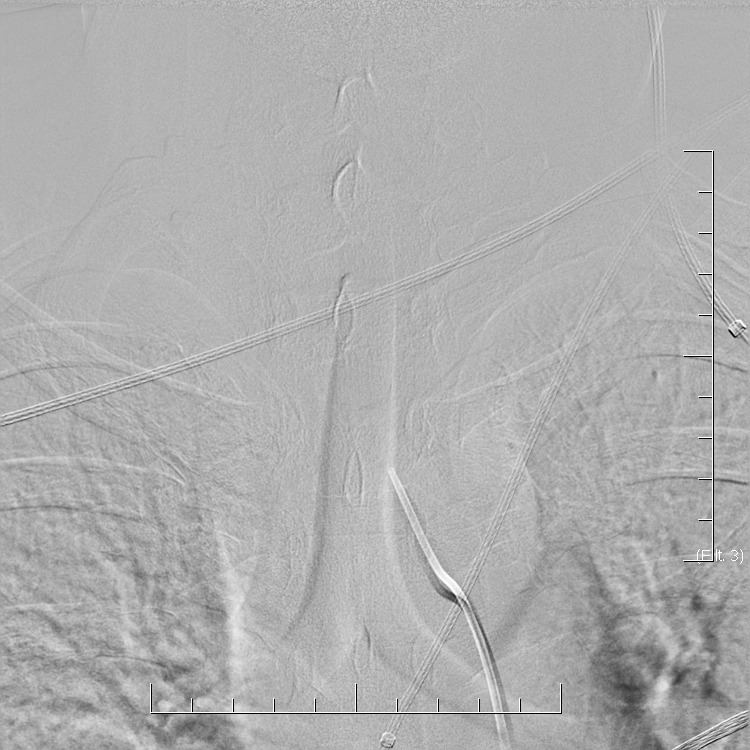

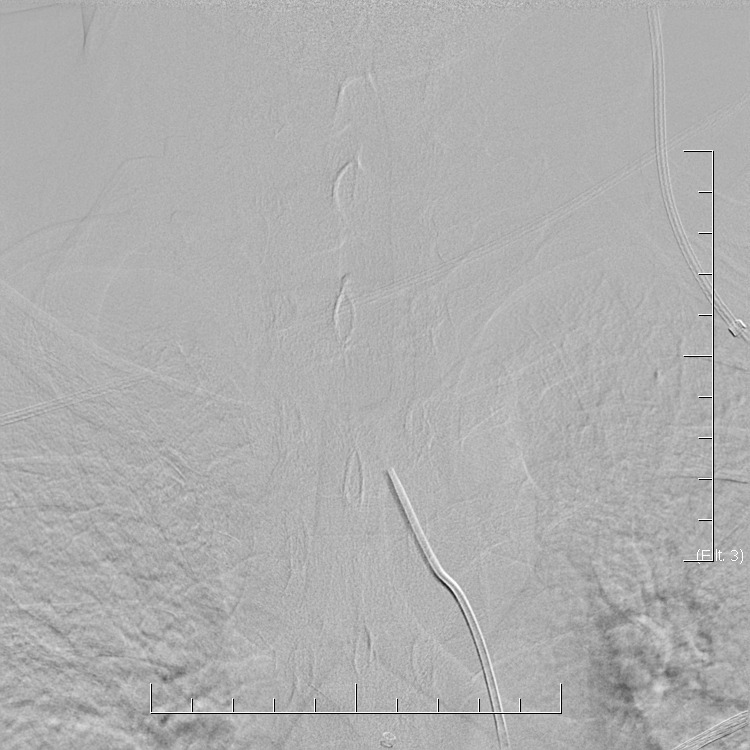

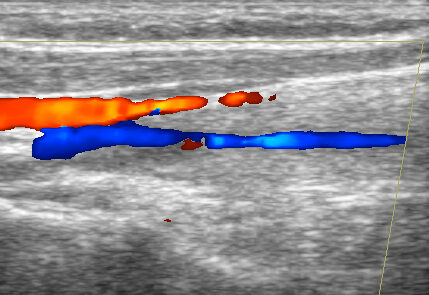

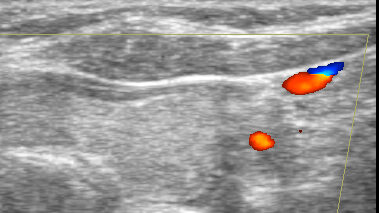

In general, the diagnosis of CNS vasculitis is very rare (< 1-3%), but also extremely difficult (especially with PACNS). It occurs predominantly in younger patients (except for temporal arteritis) without traditional vascular risk factors, manifestations/history of systemic disease, typical clinical course, and imaging findings (parenchymal and arteries involvement). Arteries may show variable degrees of stenosis, occlusion, and contrast enhancement in the wall. The correlation of neuroimaging with clinical presentation and laboratory tests helps establish the diagnosis.

- only a positive biopsy can provide a definitive diagnosis of CNS vasculitis

- if the biopsy is not performed or is negative (may be false negative), then in the presence of suspicious clinical and radiologic findings, possible CNS vasculitis can be discussed

- clinical findings indicative of vasculitis: headache (70%) and encephalopathy (up to 95%) or seizures

- no specific brain imaging pattern

- vascular imaging is typical in Takayasu arteritis and temporal arteritis

Management

Management

Detailed management and dosing is discussed in individual vasculitides

Remission induction

- corticosteroids (IV bolus)

- immunosuppressive drugs

- pulse cyclophosphamide

- cyclophosphamide PO

- plasmapheresis

- intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG)

- monoclonal antibodies

- rituximab

Remission maintaining

- PO corticosteroids + immunosuppressive drugs

- azathioprine

- methotrexate

- mycophenolate

- cyclophosphamide