ADD-ONS

Cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome (CHS)

Updated on 16/08/2024, published on 04/02/2023

-

Cerebral Hyperperfusion Syndrome (CHS) is a clinical condition characterized by a significant increase in cerebral blood flow that exceeds the autoregulatory capacity of the brain, leading to a spectrum of neurological symptoms

-

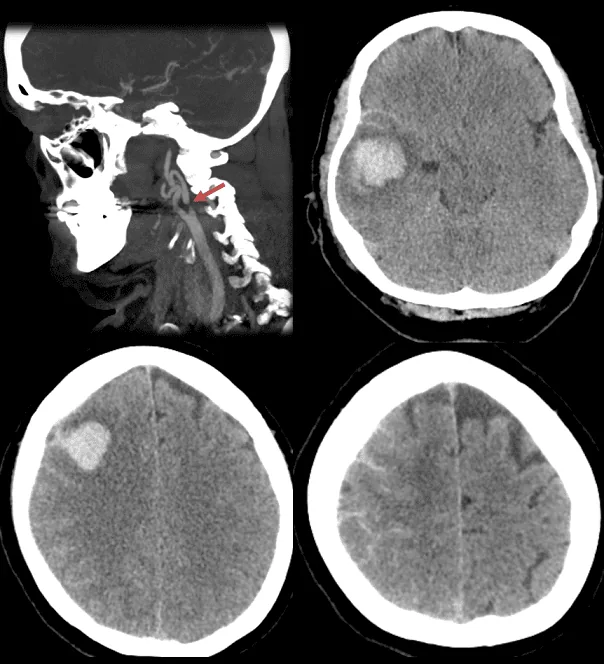

CHS can occur within hours to days after a revascularization procedure, such as carotid endarterectomy (CEA) or carotid artery stenting (CAS)

-

the peak incidence of CHS and hemorrhage after CEA is 5-7 days, while it is 12-48 hours after CAS [Ogasawara, 2007]

- a longer delay (days to weeks) has also been reported

- CHS after aortic stenosis surgery may result in bilateral lesions.

-

- diagnostic criteria include new-onset symptoms (headache, neurological deficit, and seizures) + evidence of hyperperfusion detected by TCD, MRI or SPECT

- incidence 1-14% (usually ∼ 7%)

- CEA and CAS pose similar risks (Galyfos, 2017)

- incidence seems to be higher in moyamoya surgery (Hayashi, 2012)

- the cornerstone of prevention is strict perioperative blood pressure (BP) control (for at least 14-21 days)

- TCD should be available to identify patients with hypoperfusion

Is hyperperfusion always present in symptomatic patients?

- hyperperfusion is seen in most cases of CHS, but symptoms can also occur in patients with only moderately increased CBF (30–50% above baseline) following CEA (these cases should referred to as reperfusion injury)

Procedures associated with CHS

- carotid endarterectomy

- carotid and vertebral artery stenting

- carotid and vertebral angioplasties

- extra-cranial intracranial bypass

- clipping of internal carotid artery aneurysm

- subclavian angioplasty

- revascularization in moyamoya syndrome

- repair of severe aortic valve stenosis

Pathophysiology

- the terms hyperperfusion (excessive flow/hyperemia) and reperfusion (flow normalization) are often used synonymously because both can cause cerebral injury with similar clinical presentation

- CHS results from a failure of cerebral blood flow autoregulation, leading to hyperemia

- long-term hypoperfusion, seen in conditions like high-grade stenosis, is compensated by maximal peripheral vasodilation

- the autoregulatory capacity is thus exhausted, and the blood vessels are unable to respond immediately with vasoconstriction when the perfusion pressure suddenly increases after successful CEA/CAS → tissue is therefore exposed to hyperemia

- hyperemia is usually defined as an increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF) >100% compared to the baseline → Cerebral blood flow regulation

- preoperative CBF value is usually unknown; the interhemispheric difference may be used (except in patients with contralateral stenosis)

- the risk of CHS can also be estimated using TCCD/TCD – a 1.5- or 2-fold postoperative increase in mean MCA flow velocity compared to baseline may predict the occurrence of CHS (Fujimoto, 2004)

- symptomatic CHS was also reported with a CBF increase of < 50%; in such cases, the term reperfusion syndrome should be preferred (, 2004)

- preoperative CBF value is usually unknown; the interhemispheric difference may be used (except in patients with contralateral stenosis)

- reperfusion injury (typically after acute stroke therapy) is usually caused by rapid normalization of flow within the infarcted tissue

- these patients have normal or only mildly increased CBF (20–44% above baseline)

- however, true hyperperfusion syndrome may also develop in acute stroke patients (Kneihsl, 2021)

- TCCD studies indicate that blood flow normalizes within one month after surgery; autoregulation is restored within approx. 6 weeks [Megee, 1992]

Hyperperfusion syndrome

clinical signs and symptoms + markedly increased CBF that exceeds the metabolic demand of the brain tissue, following the restoration of blood flow after a period of chronic hypoperfusion

Reperfusion syndrome

clinical signs and symptoms + normal or only mildly increased CBF occuring after acute stroke recanalization therapy

- reperfusion symptoms are increasingly recognized in various organs following revascularization procedures, such as:

- reperfusion arrhythmias

- gastrointestinal injury after reperfusion, leading to decreased intestinal barrier function

- marked polyuria following angioplasty in patients with renovascular disease

- reperfusion arrhythmias

| CHS risk factors |

|

Changes in the brain tissue resemble hypertonic encephalopathy:

- cerebral edema

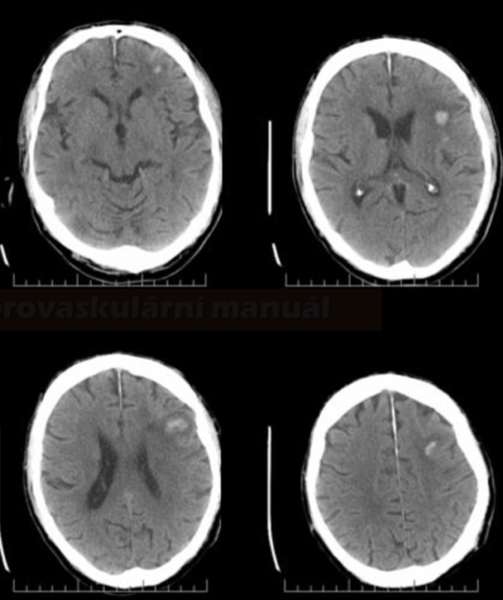

- intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) /hemorrhagic transformation of ischemia

- intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH)

- subarachnoid hemnorrhage (SAH)

Clinical presentation

- severe headache

- worsening in the prone position

- ipsilateral to the lesion side or diffuse

- impaired consciousness

- epileptic seizures (often focal)

- focal neurologic deficit (usually with ICH)

Diagnostic evaluation

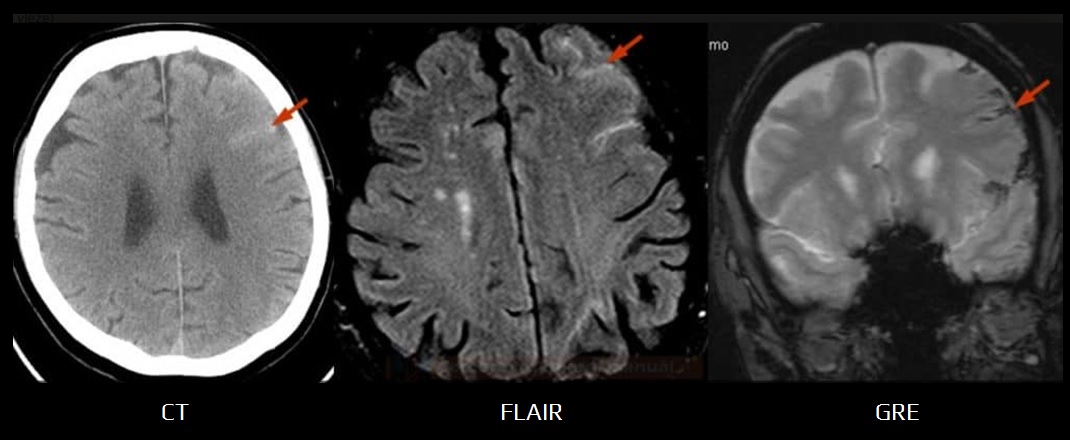

Parenchymal Imaging (CT/MRI)

- CT depicts edema/ICH/SAH in the territory of the recanalized artery

- edema is typically found in white matter (vasogenic), with or without mass effect

- bleeding can be petechial or even large parenchymal

- MRI findings may resemble those of PRES

- T2/FLAIR – diffuse hyperintense lesions

- T1C+ – possible leptomeningeal enhancement, not parenchymal

- hyperintense acute reperfusion marker (HARM) – delayed gadolinium enhancement of the cerebrospinal fluid space on FLAIR

(Cho, 2014)

- hyperintense acute reperfusion marker (HARM) – delayed gadolinium enhancement of the cerebrospinal fluid space on FLAIR

- DWI shows no lesions (typically, there is no cytotoxic edema)

- hemorrhage signal is age-dependent → MRI in hemorrhage diagnosis

Vascular imaging (CTA/neurosonology)

- CT angiography excludes thrombotic complications in the carotid artery and/or distal embolization

- TCD/TCCD shows an increased flow (↑PSV) and decreased resistance (↓PI and RI) in the MCA of >100% compared to the pre-intervention values

- an elevated PI suggests increased vascular resistance due to microembolization or intracranial hypertension

- an elevated PI suggests increased vascular resistance due to microembolization or intracranial hypertension

Perfusion imaging

- typical ipsilateral findings on CTP: ↑CBF, ↑CBV, ↓MTT

Prevention

- timing of the procedure

- benefit of CEA is greatest in the first 2 weeks following an ischemic event

- however, in cases of extensive ischemia, some delay is advisable

- perioperative TCD/TCCD monitoring

- enables early detection of hyperperfusion and the need for even stricter blood pressure (BP) control

- enables early detection of hyperperfusion and the need for even stricter blood pressure (BP) control

- strict blood pressure control

- BP reduction should be considered even in normotensive patients exhibiting hyperperfusion on TCD, as some may develop delayed hypertension

- the exact target value is unknown, and an individualized approach is advised (considering age, comorbidities, etc.)

- preferably, blood pressure should be lowered with drugs that do not increase CBF, such as labetalol and clonidine (avoid ACE-I, CCB, and especially vasodilators)

- free-radical scavengers – further trials are needed

Management

- rigorous blood pressure correction (ideally <120/80 mmHg) – it also serves as a preventive measure

-

in the case of seizure activity, administer antiseizure medication (ASM) – PHE, VPA, LEV → acute symptomatic seizures

-

start antiedema therapy

Management of patients with hemorrhagic transformation/SAH/ICH

- discontinue antiplatelet therapy and consider platelet concentrate infusion

-

administer (Solumedrol) 25-125 mg IV (to neutralize the effect of clopidogrel or other thienopyridines) [Qureshi, 2008]

- this approach is not standardized and is based on limited evidence

-

if the CT scan indicates no progression in 24 hours, patients with stents should recieve aspirin; clopidogrel therapy should be delayed for 5-7 days

Prognosis

- depends on timely recognition of hyperperfusion and adequate treatment of hypertension before cerebral edema or ICH develops

- the prognosis after ICH is poor (mortality of 36–63%, significant morbidity in the survivors)

- the prognosis of CHS in patients without ICH is much better, with low mortality

FAQs

- CHS is a potentially serious complication that can occur after procedures that restore normal blood flow to previously hypoperfused areas of the brain (CEA, CAS, etc)

- it is characterized by a significant increase in cerebral blood flow that can lead to brain edema, hemorrhage, and other neurological impairments

- CHS often occurs after procedures like carotid endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting, especially in patients with a significantly reduced cerebral blood flow and poor cerebral vascular reserve detected before the procedure (via CTP, TCD/TCCD)

- key risk factors include hypertension, intraoperative or postoperative fluctuations in blood pressure, severe carotid artery stenosis, recent TIA or stroke, and older age

- common symptoms include severe headache, seizures, focal neurological deficits (such as hemiparesis), and altered consciousness

- these symptoms typically manifest within the first week post-procedure but can occur later

- the diagnosis is primarly clinical, supported by imaging findings (MRI/CT showg cerebral edema without evidence of cerebral infarction

- TCD/TCCD can be used to monitor arterial flow velocities, which may indicate hyperperfusion

- treatment involves managing symptoms, strict blood pressure control, and sometimes the use of corticosteroids to reduce cerebral edema

- in cases of severe brain edema or hemorrhage, neurosurgical intervention may be required

- careful patient selection, preoperative assessment of cerebral vascular reserve, intra- and postoperative monitoring of cerebral blood flow, and meticulous postoperative blood pressure management

- the duration of CHS can range from days to weeks in its acute phase, with potential for longer-term effects in severe cases or when complications arise

- the prognosis varies depending on the severity of initial symptoms and the timeliness of treatment; with prompt recognition and management, many patients can recover fully

- however, severe cases involving extensive brain edema or intracerebral hemorrhage can lead to significant morbidity or mortality (such as cognitive impairment, motor function abnormalities, or epilepsy)