ADD-ONS / OTHER VASCULAR DISORDERS

Carotid Body Tumor

Updated on 02/05/2024, published on 21/11/2021

- the carotid body tumor (glomus tumor) is a rare tumor, but it represents the most common extra-adrenal paraganglioma

- more common in females, typically diagnosed in the 4th to 5th decade of life

- most cases are sporadic; 10% are hereditary

- familial tumors present earlier (typically in the 4th decade) and are more frequently multicentric

- association exists with multiple endocrine neoplasia ( MEN IIa and MEN IIb), tuberous sclerosis complex (TS), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), von Hippel-Lindau disease (vHL)

- bilateral occurrence is observed in ~ 10% of cases

- histologically similar tumors can also originate from the jugular bulb, sympathetic vagal ganglia of the neck (glomus vagale tumor

), Jacobsen’s tympanic plexus of the middle ear, retroperitoneal sympathetic and visceral parasympathetic ganglia. Spinal paragangliomas are rare and occur intradurally extramedullary, usually in the region of the filum terminale/cauda equina, or less frequently, extradurally

- more common in females, typically diagnosed in the 4th to 5th decade of life

- hypervascularization is a hallmark feature of glomus tumors

- due to the absence of neuroendocrine secretion, they are classified as chemodectomas (chemoreceptor tumors)

- in sporadic cases, catecholamine secretion and associated hypertensive symptoms may be present

- most head and neck paragangliomas are benign yet locally invasive

- approximately 2–13% of paragangliomas demonstrate malignancy

- malignancy is defined by metastasis, as there are no histopathologic criteria that can accurately differentiate malignant from benign paragangliomas

- metastases are usually regional (in the neck); distant metastases are rare (Boedeker, 2007)

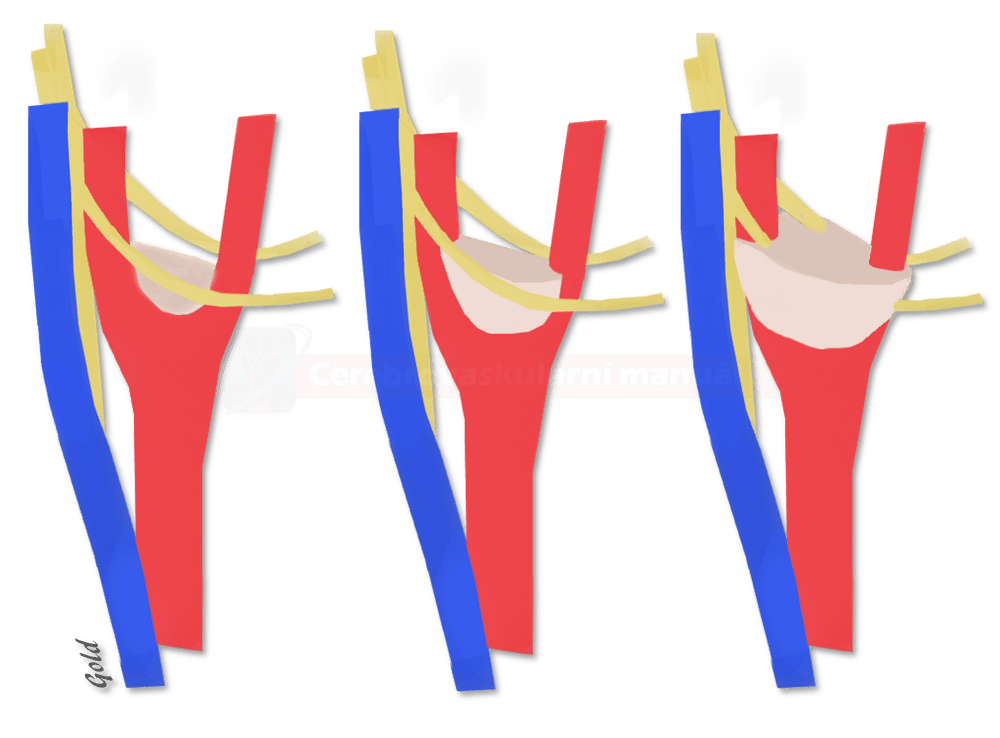

Classification

To assess the extent and operability of tumors and to predict postoperative morbidity, the Shamblin Classification is used:

Clinical presentation

- most often, the tumor presents as a painless, elastic, pulsating, slowly growing rounded mass in the neck (located anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, near the mandibular angle)

- larger tumors cause head/neck pain, dysphonia, and other symptoms resulting from the involvement of multiple cranial nerves (CN IX, X, XI, and XII)

- upon palpation, the mass moves horizontally but not vertically due to its fixation at the CCA bifurcation (Fontaine’s sign)

- endocrine activity is less common compared to adrenal paragangliomas (pheochromocytomas)

Diagnostic evaluation

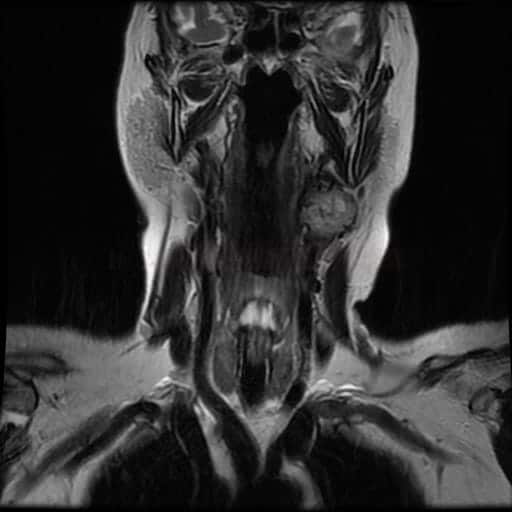

CT/MRI

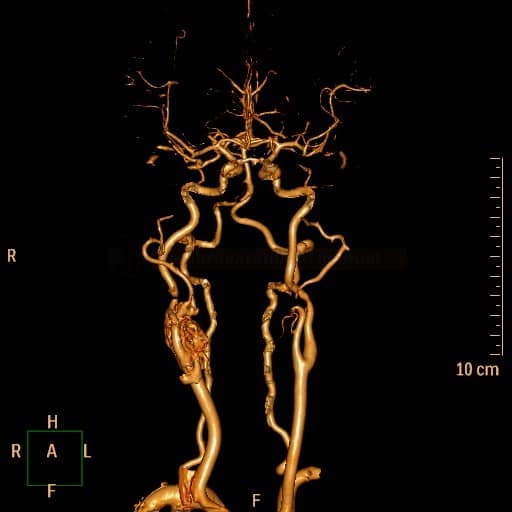

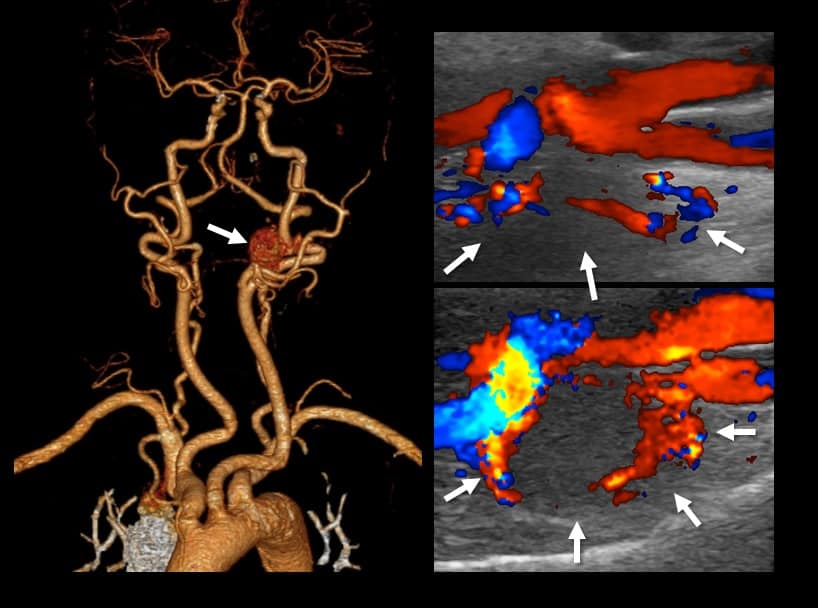

CT / CTA

- the tumor exhibits soft tissue density with rapid enhancement

- as the tumor grows, a splaying of the origin of ICA and ECA occurs (“lyra” sign)

- CTA shows a hyper-vascularized mass at the carotid bifurcation with early venous filling due to arteriovenous shunting

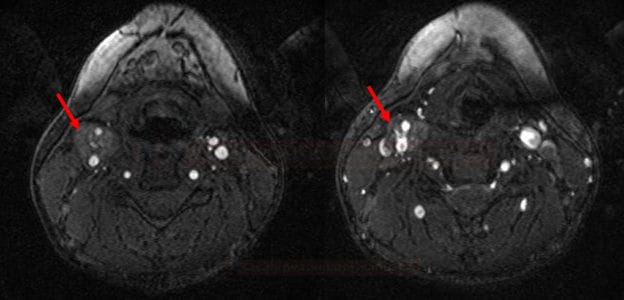

- the maximum circumferential contact of the tumor with the ICA on axial images can predict the Shamblin group (Arya, 2008)

- group I: <180 degrees of encasement

- group II: 180-270 degrees of encasement

- group III: >270 degrees of encasement (probable adventitial involvement necessitating ICA resection

Functional imaging

- a significant advantage of functional (metabolic) imaging is its capability to examine the entire body – useful for detecting multifocal or metastatic disease

- 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (123I-MIBG) scintigraphy

- suitable for detecting multiple lesions

- applicable only in patients with hormonally active tumors

- 111In-pentetreotide (148 MBq) scintigraphy – utilizes a radiolabeled somatostatin analog that preferentially binds to the somatostatin receptor type 2 (SST2), which is highly expressed in paragangliomas

- superior to 123I-MIBG scintigraphy for diagnosing and localizing chemodectomas (Muros, 1998)

- applicable in hormonally inactive tumors

- superior to 123I-MIBG scintigraphy for diagnosing and localizing chemodectomas (Muros, 1998)

- 18F-FDG PET – sensitive but not specific for CBT

- effective for the detection of metastatic disease

Laboratory studies

- monitoring of plasma levels of catecholamines and their metabolites in urine

- due to the absence of endocrine secretion in the vast majority of carotid glomus tumors, this is important for differential diagnosis

If a glomus tumor is suspected, a biopsy should not be performed due to the tumor’s strong vascularization and high risk of bleeding

Differential diagnosis

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

Management

Surgery

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

Radiosurgery

- carotid body tumors are generally considered radioresistant + tumors treated primarily with radiation become difficult to resect (due to radiation-induced fibrosis) ⇒ therefore, surgery is the treatment modality of choice

- the primary objective of radiotherapy is to slow disease progression

- radiotherapy is reserved for large or multicentric tumors in patients with surgical contraindications or unfavorable balloon test occlusion (BTO) findings

- radiotherapy may also serve as an adjuvant following incomplete extirpation

- radiotherapy is reserved for large or multicentric tumors in patients with surgical contraindications or unfavorable balloon test occlusion (BTO) findings

Prognosis

- in most cases, a complete cure is achievable with surgery

- risk of recurrence ~ 10%

- tumor growth is slow; therefore, long-term survival is possible even with advanced tumors – an annual mortality rate of <8% has been reported in untreated patients

- cranial nerve damage resulting from tumor compression is usually irreversible

- follow-up MRI is recommended due to the risk of recurrence or late metastases