ISCHEMIC STROKE / COMPLICATIONS

Acute ischemic stroke complications

Updated on 21/05/2024, published on 20/02/2023

- typically, the neurological deficit is maximal at the onset of the ischemic stroke and may subsequently improve (either spontaneously or due to recanalization therapy)

- however, stroke patients are at risk of a variety of complications that may lead to death or clinical deterioration, manifested by:

- progression of existing deficits or appearance of new symptoms (due to new occlusion, progression of existing thrombosis, edema, or hemorrhage)

- quantitative or qualitative impairment of consciousness

- delirium

- epileptic seizures

- intracranial hypertension

- mood disorders

- worsening of preexisting comorbidities (cardiac, respiratory, etc.)

- onset of new systemic disorders (infection, venous thromboembolism, infarction, etc.)

- complications can be divided into intracranial and extracranial; a brief overview follows

Diagnostic evaluation

- general and neurological examination

- review medication (sedatives, delirium-inducing drugs)

- follow-up CT/MR of the brain (large edema? hemorrhage? new infarct lesion? hydrocephalus?)

- follow-up vascular imaging (neurosonography/MRA/CTA)

- new occlusion in another segment? reocclusion of recanalized artery?

- hemodynamically significant stenosis?

- collateral circulation failure?

- EEG examination (or EEG monitoring)

- ECG monitoring

- other imaging studies

- chest X-ray

- abdominal ultrasound

- CT scan of the chest, abdomen, or pelvis

- laboratory tests:

- basic metabolic panel, CBC + coagulation tests

- arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis (arterial pH, PaO2, PaCO2, and “base excess”

- test provides valuable information about the patient’s acid-base balance, oxygenation, and ventilation status, which are crucial in the management of stroke and other critical conditions

- normal arterial pH: 7.35-7.45

- CRP, procalcitonin

- cardiac enzymes to assess the myocardial injury

- troponin T (TnT) and troponin I (TnI)

- creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB)

- Mg, Ca, ammonia

- basic metabolic panel, CBC + coagulation tests

- detection of infection

- sputum and urine analysis, culture swabs

- blood cultures

Intracerebral complications

- approximately 30% of acute stroke patients experience progression of neurological deficits, including quantitative or qualitative disturbances of consciousness

- deterioration may be gradual (typically due to edema or thrombus progression) or sudden (new embolism, abrupt failure of collateral circulation, or intracranial bleeding, etc)

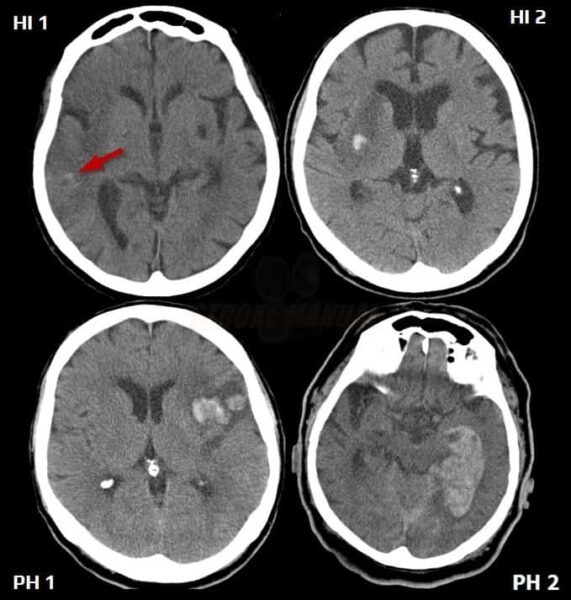

Hemorrhagic transformation of ischemia

- the hemorrhagic component is easily detected on CT and even better on MR GRE

[Arnauld, 2003]

- hemorrhagic transformation most commonly occurs within the first 48 hours; increased risk is associated with extensive ischemia, late recanalization, and early anticoagulation

- hemorrhagic transformation is often asymptomatic

- antiplatelet therapy/LMWH should be discontinued if major bleeding occurs

Brain edema, intracranial hypertension

- edema usually develops between days 2-5

- initially intracellular (cytotoxic)

- a vasogenic component can be seen from day 5

- symptomatic edema can be expected in large supratentorial ischemias and cerebellar infarcts

- clinical presentation:

- worsening of the neurological deficit (including loss of consciousness) within 24-36 hours

- gradual progression over several days

- initial deterioration is followed by a plateau and gradual improvement over a week (except for malignant edema cases)

- worsening of the neurological deficit (including loss of consciousness) within 24-36 hours

- efficacy of pharmacotherapy is unclear (AHA/ASA 2013 IIb/C)

- ventricular drainage and/or craniectomy is recommended if acute hydrocephalus develops as a result of a posterior fossa stroke (AHA/ASA 2013 I/C)

- decisions regarding decompressive craniectomy should be made early in cases of malignant ischemia

Ischemia progression / early stroke recurrence

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

Acute symptomatic epileptic seizures (ASS)

- according to various sources, stroke is responsible for up to 60% of all acute symptomatic seizures (ASS)

- seizures are typically focal, with possible secondary generalization

- most seizures occur in the first 48 hours after stroke onset; increased risk of ASS is associated with large cortical ischemia and intracerebral bleeding

Delirium

- delirium (historically known as acute confusional state) presents with disturbances in attention, awareness, and higher-order cognition

- commonly attributable to:

- brain lesion

- extracerebral causes: medication, metabolic disorders, alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS), infection, etc.

- Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome (AWS) is a set of symptoms that can occur following a reduction in alcohol consumption after a period of excessive and/or prolonged use (besides delirium, tremor, anxiety, nausea, hallucinations, or seizures can be seen)

- Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome (AWS) is a set of symptoms that can occur following a reduction in alcohol consumption after a period of excessive and/or prolonged use (besides delirium, tremor, anxiety, nausea, hallucinations, or seizures can be seen)

- combination of both intracerebral and extracerebral factors

| Delirium-inducing drugs |

|

anticholinergic drugs

|

|

|

Addictive substances and alcohol (acute toxicity/ withdrawal)

|

|

H2-blockers (cimetidine, ranitidine)

|

|

opioid analgesics

|

|

antimalarial drugs (mefloquine)

|

|

antiviral drugs (acyclovir)

|

|

others (lithium, barbiturates, benzodiazepines flunitrazepam, NSAIDs indomethacin, digoxin, corticosteroids, centrally acting myorelaxants, antihypertensives

|

Failure of collateral circulation

- the risk of collateral circulation failure is increased in the presence of concurrent extra-intracranial stenoses and/or hypotension

- typical watershed infarcts can be seen in such settings

- maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) >110 mmHg in normotensive patients and >130 mmHg in patients with known hypertension for the first 24 hours

- administer plasma expanders or vasopressors if needed

Extracerebral complications

Infectious complications

- fever is most commonly caused by respiratory infections

- preventive measures for aspiration bronchopneumonia include early detection of dysphagia and early indication for NG tube placement

- preventive measures for aspiration bronchopneumonia include early detection of dysphagia and early indication for NG tube placement

- urinary tract infections are associated with catheter use

- catheter-related bloodstream infections (→ sepsis)

Metabolic disorders

- hydration disorders (usually dehydration)

- ionic imbalances (most commonly hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia, etc.)

- renal or prerenal uremia

Cardiovascular complications

- several heart conditions (such as valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and myocardial infarction) are significant risk factors for stroke

- acute stroke can also induce cardiac dysfunction (e.g., arrhythmias) or lead to other cardiac complications

- worsening of preexisting cardiomyopathy (CMP) or congestive heart failure (CHF)

- a risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality

- acute decompensation may occur due to myocardial infarction (MI), tachyarrhythmias, transfusion, or antiedema therapy

- acute stress cardiomyopathy (Tako-Tsubo)

- characterized by bulging of the apical part of the ventricle, ST-segment elevation with negative T waves in leads V3 and V4

- cardiac enzymes are typically normal

- females are more commonly affected

- myocardial infarction with hypokinesia may be a source of cardiac embolism, but MI may also be a consequence of stroke (autonomic dysregulation, stress)

- elevation of cardiac enzymes due to neurogenic myocardial damage (myocytolysis) is a frequent finding; exclusion of MI is imperative

- more common in polymorbid patients with previously established coronary artery disease (CAD) and vascular risk factors (such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, etc.)

- decompensated hypertension or hypertensive crisis (emergency) occurs in up to 80% of stroke patients

- etiology is complex, involving compensatory mechanisms aimed at improving perfusion and stress response

- hypotension is generally defined as SBP < 90 mm Hg or DBP < 60 mm Hg

- the clinical threshold (leading to hypoperfusion symptoms including border zone infarction) is individual (higher in hypertensive patients)

- most common causes of hypotension in acute stroke patients are:

- heart failure

- hypovolemia/shock

- anemia

- sepsis

- arrhythmias (dysrhythmias) are irregularities in heart rhythm and are a common complication of acute stroke

- the most common are supraventricular arrhythmias

- sinus tachycardia

- atrial fibrillation/flutter

- arrhythmias may cause:

- hemodynamic instability with hypotension (↑risk of hypoperfusion injury)

- congestive heart failure, potentially leading to pulmonary edema, etc.

- atrial fibrillation/flutter increases the risk of cardioembolism

Respiratory complications

- hypoxia leads to a progression of brain damage, transitioning from penumbra to necrosis and potential worsening of neurological deficit

- the most common causes of respiratory failure are:

- impaired airway clearance

- congestion, difficulty coughing (due to bulbar syndrome or somnolence) ⇒ hypoxemia, hypercapnia

- airway obstruction

- aspiration pneumonia

- often a combination of aspiration and congestion/difficulty in coughing

- increased risk in drowsy patients and those with bulbar syndrome

- early screening for dysphagia may prevent pneumonia

- central respiratory disorders (due to primary and secondary brainstem lesions)

- pulmonary edema, atelectasis

- pulmonary embolism

- decompensation of asthma bronchiale (caution when using beta-blockers)

- impaired airway clearance

Gastrointestinal complications

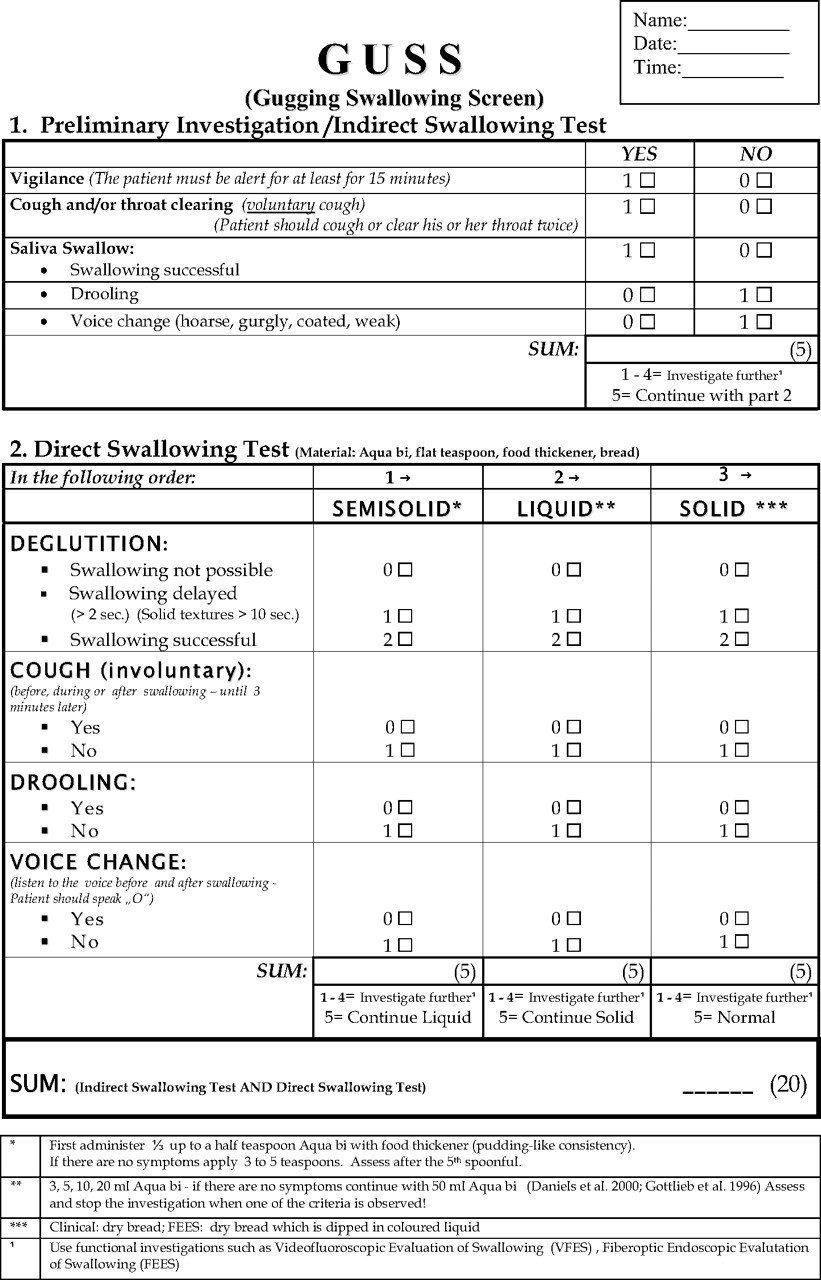

- dysphagia is present in 42-67% of patients with acute stroke in the first three days

- the most severe dysphagia is seen in patients with brainstem lesions

- dysphagia is associated with an increased risk of aspiration

- the incidence of aspiration in the first five days ranges from 20% to 42%

- aspiration/silent aspiration is a frequent cause of bronchopneumonia

- systematic screening for dysphagia reduces the risk of aspiration-related bronchopneumonia

- recommendations:

- screening for dysphagia before initiating per os intake (including medications) – effective in identifying patients at increased risk of aspiration (AHA/ASA 2019 I/C-LD)

- optimally, screening should be performed by a speech and language therapist or other specially trained professional

- a standardized protocol is recommended

- implementation of oral hygiene protocols

- early nasogastric (NG) tube placement if dysphagia is evident, followed by swallowing training

- dietary modifications for milder cases

- if dysphagia persists beyond 2-3 weeks, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) should be indicated (AHA/ASA 2019 IIa/C-EO)

- screening for dysphagia before initiating per os intake (including medications) – effective in identifying patients at increased risk of aspiration (AHA/ASA 2019 I/C-LD)

- screening tests

- GUSS test

- water swallow test (original and modified)

- the most common cause of GI bleeding is either a preexisting lesion or a newly developed “stress ulcer”

- disruption of the integrity of the upper GI mucosa due to extreme physiological stress, typically in critically ill patients

- often develops within a few hours after the initial insult

- can result in bleeding or perforation ⇒ ↑ mortality and intensive care stay

- incidence approx. 3% when on prophylactic medication

- risk factors for GI bleeding

- coagulopathies, including iatrogenic

- history of GI bleeding/peptic ulcer

- mechanical ventilation > 48h

- traumatic brain/spinal cord injury

- sepsis

- corticosteroids use

- renal and hepatic impairment

- malignancy

- severe stroke

- initiate enteral nutrition as soon as possible!

- prophylaxis should be administered only to patients at increased risk and discontinued in a timely manner (due to the increased risk of nosocomial pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infection, drug interactions, or hepatotoxicity); routine use of PPIs does not reduce mortality

- proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

- PPIs are more expensive and significantly more effective than H2-blockers [Buendgens, 2016]

- use H2 blockers if PPIs are contraindicated

- 40 mg once daily, or 20 mg twice daily PO

-

- 1g PO or via nasogastric tube every 6-8 hours

- used in peptic ulcer prevention and treatment or to reduce hyperphosphatemia

- caused by a clonic contraction of the diaphragm with simultaneous closure of the glottis

- short-term hiccups are mostly benign and can be attributed to factors such as:

- distention of the esophagus and stomach, intake of carbonated fluids, irritation of the digestive tract with spices

- emotions, excitement

- sudden change in temperature: drinks (hot/cold), shower, air, etc.

- more serious underlying causes:

- pulmonary and mediastinal diseases (pneumonia, lung tumors, mediastinitis, and mediastinal tumors)

- abdominal cavity diseases (direct irritation of the diaphragm – ileus, peritonitis, stomach and liver tumors and metastases, liver abscess, pancreatitis, and pancreatic tumors, etc.)

- heart diseases (pericarditis, myocardial infarction)

- esophageal diseases (oesophageal obstruction by solid food or tumor, or esophagitis)

- metabolic causes (uremia, diabetes decompensation), acid-base disorders, mineral imbalances (hyponatremia)

- central causes (direct or indirect brainstem lesions) – tumors, stroke, trauma

- alcohol and drugs (dexamethasone, methyldopa, sulfonamides, antiseizure medications)

- severe forms of hiccups are frequently resistant to symptomatic treatment

- treat potential causes

- pharmacotherapy (see table) – combination therapy may be effective (e.g., omeprazole + baclofen + gabapentin)

- psychotherapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy or other psychological interventions may be beneficial for stress-induced hiccups)

- acupuncture (may provide symptomatic relief, particularly for hiccups resistant to pharmacotherapy)

| BACLOFEN (has a peripheral and central effect) |

|

| Anticonvulsive drugs |

|

| gabapentin (NEURONTIN) |

|

| valproate (ORFIRIL, DEPAKINE) |

|

| Neuroleptics (central effect) | |

| HALOPERIDOL |

|

| chlorpromazine (PLEGOMAZIN) |

|

| Prokinetic drugs |

|

| metoclopramide |

PO 10 mg every 6-8 hours (max 40 mg/d) |

| PPI (use if GER is suspected) | |

| omeprazole pantoprazole |

PO 20-40 mg once daily |

Urogenital complications

- urinary incontinence

- urinary tract infections (up to 15%)

- may lead to worsening of the clinical condition

- prevention:

- avoid unnecessary catheterization and regularly review the necessity of an indwelling catheter and remove it as soon as clinically feasible

- employ sterile technique during catheter insertion and maintenance

- use antibiotic-coated or silver-alloy catheters to reduce the risk of bacterial colonization

- perform routine urine tests to detect early signs of infection

- ensure adequate fluid intake to promote urinary flow and dilute bacteria

- encourage early mobilization

Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism

Other complications

- Poststroke Depression (PSD) is quite common (in up to 33% of patients)

- depressed patients are less compliant with physical therapy and medical treatment and have worse outcome compared to non-depressed patients

- early drug treatment (tricyclics, SSRIs, SNRIs) is important

- anxiety

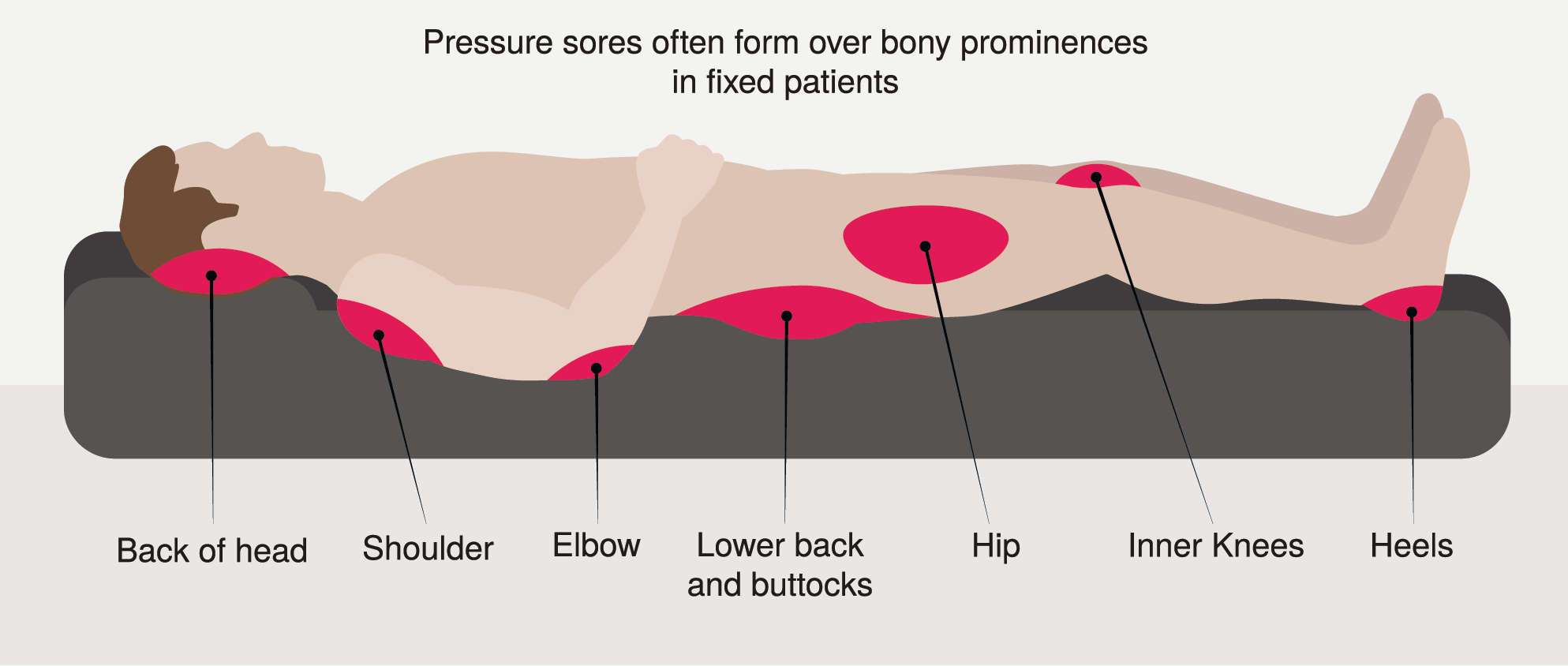

- pressure sores usually occur on the back of the head, shoulders, elbows, sacrum and buttocks, hips, and heels

- prevention of pressure sores:

- rule out fracture or luxation (often caused by a fall due to sudden onset of paresis)