ISCHEMIC STROKE

Stroke mimics

Updated on 24/06/2024, published on 24/05/2023

- stroke is a medical emergency presenting with focal neurological deficits; stroke mimics are non-vascular conditions that present with symptoms similar to those of stroke

- incidence of stroke mimics is ~3-10% [Okano, 2018] [Winkler, 2009] [Scott, 2003] [Tsivgoulis, 2011]

- the most common mimics are epileptic seizures, migraine, brain tumors, functional disorders, TGA, hypoglycemia and other metabolic disorders, syncope, or intoxication

- the existence of mimics causes troubles in the acute setting (should we initiate thrombolysis?) but also in the chronic stage (is it a recurrent stroke? should we change the secondary prevention? is CEA indicated for carotid stenosis?)

- incorrectly administered IVT may harm the patient, although available data show the relative safety of thrombolysis in stroke mimics [Tsivgoulis, 2011]

- on the other hand, failure to adequately treat unrecognized stroke reduces chances for recovery

- it is essential to consider stroke mimics in the differential diagnosis of every patient with suspected stroke; however, potential candidates for thrombolytic therapy should not be excluded based on the sole concern that their neurological symptoms may be due to stroke mimics

| Characteristic | Probable stroke | Probable mimics |

| age and sex | older age (male = female) | younger age (females > males) |

| level of consciousness | usually awake at the onset (except for extensive vertebrobasilar occlusion) |

altered level of consciousness |

| onset and progress | acute and sudden | gradual |

| symptoms severity | severe at onset | fluctuations are common, usually milder deficit |

| risk factors | vascular risk factors | history of migraine, seizure, systemic illness, cognitive impairment |

| vascular territory | vascular syndromes | symptoms not corresponding to a single vascular territory |

| blood pressure at presentation | increase blood pressure is common | blood pressure usually not increased |

| signs and symptoms | focal deficit (limb paresis, gaze deviation, aphasia, or visual field defects) |

sensory symptoms, vertigo, and visual symptoms, often an absence of focal neurologic signs |

| involuntary movements | uncommon | may be present |

| imaging |

ischemic lesion or vessel occlusion, perfusion mismatch on CTP or MRI (dense sign on NCCT, occlusion on CTA) |

lesions not respecting the vascular territories |

| EEG | EEG may show slowing over the affected area | spikes and waves in seizures, PLEDS |

Recrudescence |

- recurrence of previous stroke-related deficits in the settings of metabolic, infectious, and toxic dysfunction

- may develop within weeks to years after the previous stroke

- DWI excludes new stroke

- symptoms are usually short-lived, resolving within 24 hours in most individuals

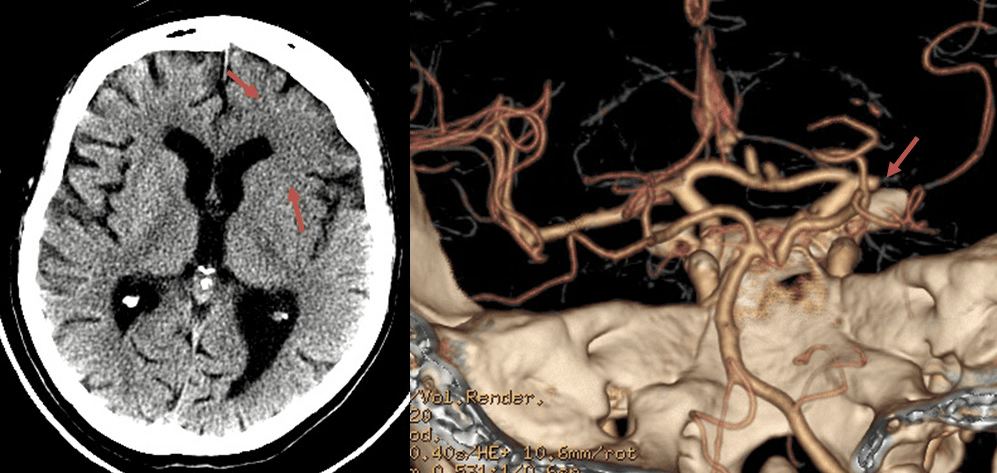

Nontraumatic convexal (focal) SAH |

- a rare cause of transient symptoms

- more common in older patients (> 60 years) [Beitzke, 2011]

- MRI confirms the diagnosis (with almost 100% sensitivity); thin-sliced multiplanar CT is also a valuable emergency diagnostic tool (however, MRI remains crucial and mandatorily and must be completed within the next 24–72 hours) [Ertl, 2014]

Transient symptoms in CAA (amyloid spells)

|

- amyloid spells in CCA represent a stroke mimic associated with ↑risk of ICH after IVT administration → Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)

Stroke-like episodes in Sturge-Weber syndrome

|

Epileptic seizure

|

- epileptic seizure may mimic a stroke, and the patient may be mistakenly treated with thrombolysis

- conditions such as Todd’s hemiparesis, complex focal seizures mimicking symbolic dysfunction, etc., are challenging in the acute stage

- epileptic seizures can also occur in the terrain of previous ischemia (poststroke epilepsy) and transiently worsen the previous deficit

- conditions such as Todd’s hemiparesis, complex focal seizures mimicking symbolic dysfunction, etc., are challenging in the acute stage

- however, epileptic seizures can also occur during an acute stroke (~1-6%), and the patient may not receive appropriate recanalization therapy if misdiagnosed as a pure seizure [Sylaja, 2006] [Killpatrick, 1990]

- thrombolytic therapy is not contraindicated for a stroke patient experiencing an epileptic seizure as long as imaging confirms the stroke (occlusion on CTA, perfusion mismatch, fresh DWI lesion, etc.)

Clinical presentation

- symptoms indicative of a seizure → classification of seizures

- focal seizures

- isolated positive motor or sensory symptoms (FAS)

- altered awareness (FIAS)

- gradual spread (march)

- uniform attacks

- sometimes a therapeutic test with AE can be helpful in establishing the correct diagnosis

- generalized seizures

- motor (tonic-clonic convulsions or others) or non-motor components (absence)

- postictal confusion

- lost bladder control

- tongue and/or cheek injury

- focal seizures

- objective history

- a typical course of seizure, and a history of similar seizures in the past

- in general, any initial transient disturbance of consciousness should raise suspicion of another etiology

Diagnostic evaluation

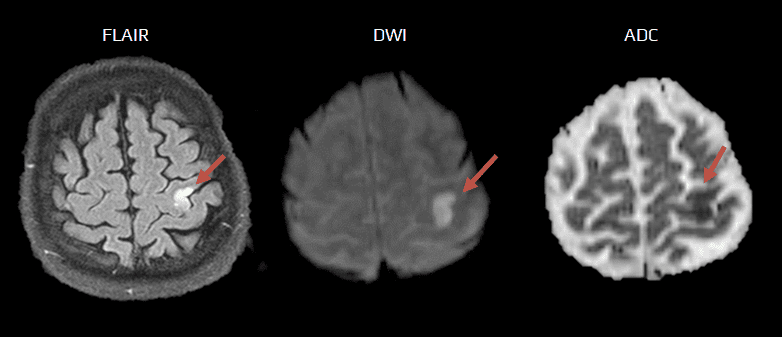

- in unclear cases, imaging methods can help:

- demonstration of arterial occlusion on CTA

- demonstration of early ischemia on CT (ASPECTS)

- demonstration of fresh ischemia on DWI with the corresponding hypointensity in the ADC map

- positive CT perfusion

- prolactin may already be normal on arrival at the hospital (peak around 30 minutes), and the result is not available acutely

Migraine |

- a frequent stroke mimic

- migraine aura without the headache and the first attack of basilar or hemiplegic migraine represent the main problems

- symptoms usually develop more slowly, spread or migrate, and are typically followed by headache with nausea/vomiting and photo-/phonophobia (see table)

- migraine is likely:

- in younger patients with a history of similar recurrent attacks and no vascular risk factors

- with positive symptoms developing within minutes or tens of minutes (gradual onset)

- flashes, bright lines, and scintillations that begin in part or half of the visual field and may extend to the entire visual field or often move across the visual field

- paresthesias usually spreading or moving over half the body (march), including the head, over minutes to tens of minutes

- with subsequent development of headache

- history of repeated uniform attacks with a slow onset may be helpful

- if symptoms resolve rapidly, DDx of TIA can be problematic (mainly if the condition occurs for the first time)

- imaging, including MR-DWI or CT perfusion, is normal

- dissection should be ruled out in new-onset hemicrania with focal findings!

Migraine characteristics (must meet at least 2 of the following):

|

| TIA | Migraine aura | |

| personal history |

usually no history of a similar attack |

repeated attacks |

| symptoms onset |

sudden (seconds) | gradual (> 5 min) |

| duration | mostly minutes |

approx. 20-30 min (< 60 min) |

| timing | focal symptoms with concurrent headache | focal symptoms precede the headache |

| visual disorders |

monocular disorders hemianopia |

positive scintillating scotomas, gradually spreading across the entire visual field

negative scotomas |

| headache | migraine headache criteria see above headache most commonly follows focal symptoms but may be absent |

Stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) syndrome |

- SMART syndrome (stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy) is a delayed complication of brain radiotherapy (usually associated with doses of ≥50 Gy)

- onset of symptoms varies widely from 1 to 40 years after initial radiation therapy

- symptoms last from several hours to several weeks and typically consist of:

- recurrent headaches with migraine-like aura

- seizures

- stroke-like symptoms referable to a unilateral cortical region (motor deficits, paresthesias, aphasia, and visual disturbances)

- full recovery in most patients has been reported

- imaging findings may include unilateral increased T2 signal with associated gyral thickening and transient cortical enhancement in the temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes; the process spares the white matter

- the pathogenesis is not as well understood as other complications of radiation, such as leukoencephalopathy and radiation necrosis

- proposed endothelial dysfunction may lead to disruption of the blood-brain barrier with subsequent marked cortical enhancement

- some case reports have described nonspecific gliosis without inflammation or no identifiable histopathologic abnormalities

Metabolic and toxic encephalopathies |

- mental status changes and epileptic seizures with possible Todd’s hemiparesis predominate in most encephalopathies (renal, hepatic failure)

- impaired level of consciousness may progress

- complications may occur even after hemodialysis (see below)

- neuroglycopenia and Wernicke encephalopathy, in particular, may present with focal symptoms, which are the most difficult to differentiate from a true stroke

Hypertensive encephalopathy |

- may accompany decompensated hypertension (usually with SBP > 220 mmHg/DBP > 120 mmHg) → hypertensive crisis

- the rate of BP increase seems to be more important than its absolute value

- failure of autoregulation leads to cerebral edema

- clinical presentation:

- confusion, headache, nausea/vomiting, visual disturbances, focal symptoms

- papilledema and hypertonic retinopathy on ophthalmoscopy

- reversible posterior hypertensive encephalopathy (PRES) may occur

Multiple sclerosis

|

- DDx of a first attack of multiple sclerosis (MS) from a stroke and recognition of the coincidence of MS and acute stroke may pose problems

- the most difficult decision is whether to administer IVT or not

- age and the presence or absence of risk factors cannot be relied upon (stroke is increasingly seen in young patients without vascular risk factors)

- in addition, MS can manifest at older ages (40-50 years) when patients may already have multiple vascular risk factors present

- the most difficult decision is whether to administer IVT or not

- findings of occlusion on CTA, perfusion defects on CTP, or early signs of ischemia (ASPECTS<10) are helpful

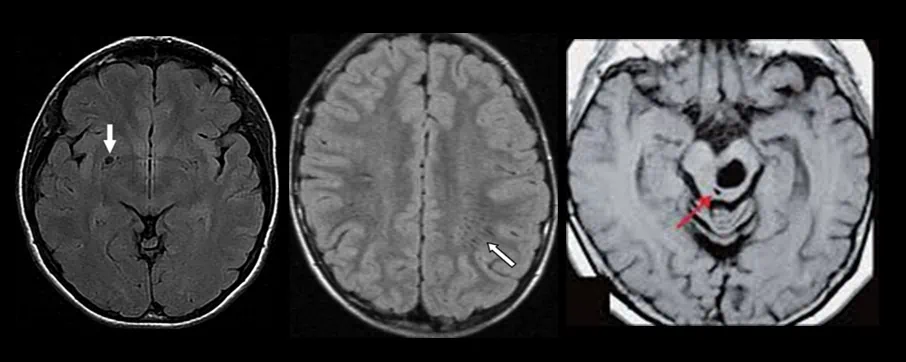

- MR DWI

- acute plaque may present with diffusion restriction on DWI ⇒ small lesions cannot be reliably distinguished radiologically from lacunar infarct (Davoudi, 2016)

- postcontrast enhancement of the lesion may help

- larger ischemic lesions can be distinguished by their typical shape and location corresponding to an arterial territory

- acute plaque may present with diffusion restriction on DWI ⇒ small lesions cannot be reliably distinguished radiologically from lacunar infarct (Davoudi, 2016)

Peripheral vestibular syndromes |

- typical association with position change

- dizziness and nystagmus can be provoked by specific positional tests (Dix-Hallpike, Seemont, Log-roll, etc.)

- an acute vestibular syndrome characterized by sudden-onset severe vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and gait instability, without auditory symptoms

- it results from inflammation of the vestibular nerve, often due to viral infection

- diagnosis is clinical, supported by head impulse tests and the absence of central neurological signs

- management includes corticosteroids, antiemetics, and vestibular rehabilitation

- recovery is typically gradual over weeks to months, with most patients experiencing significant improvement

- Ménière’s disease is an inner ear disorder causing vertigo, tinnitus, hearing loss, and aural fullness

- it results from endolymphatic hydrops

- diagnosis is clinical, supported by audiometry and vestibular testing

- management includes lifestyle modifications, medications, and, in refractory cases, surgical interventions

- acetazolamide, hydrochlorothiazide, bethistine

- vestibular paroxysmia is a vestibular disorder characterized by brief, recurrent episodes of vertigo lasting seconds to minutes, often triggered by head movements

- auditory symptoms like tinnitus or hearing loss may occur

- it results from vascular compression of the 8th cranial nerve

- diagnosis involves clinical evaluation, MRI, and response to carbamazepine/oxcarbazepine

- initial dose: 100-200 mg twice daily, then increase gradually based on patient response and tolerability

- maintenance dose: typically 400-1200 mg daily, divided into two or three doses

- microvascular decompression is considered in refractory cases

Transient global amnesia (TGA) |

- a sudden, temporary (< 24h) episode of memory loss in the absence of other neurological signs and symptoms

- memory loss cannot be attributed to a more common neurological condition, such as epilepsy or stroke → more here

Tetany

|

- tetany is usually manifested by involuntary muscle cramps due to electrolyte abnormalities (most commonly hypocalcemia)

- diagnostic difficulties can be caused by isolated paresthesia

Brain disorders with structural lesions |

- these disorders can be differentiated by neuroimaging (CT/MRI)

- intracerebral or spinal hemorrhage

- differentiate hemorrhagic infarction (arterial and venous)

- differentiate hemorrhagic infarction (arterial and venous)

- tumor – acute deterioration may be caused by bleeding into the tumor due to decompensation of edema or epileptic seizure

- neuroinfectious diseases

- fever, headache, elevation of inflammatory markers, mental status changes, epileptic seizures

- autoimmune encephalopathy

- gradual onset

- typical MRI presentation with temporal lobe predilection

- abnormal EEG

- autoantibodies (not available in the acute phase)

- PRES (Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome)

- a neurological condition characterized by reversible subcortical vasogenic edema predominantly affecting the posterior regions of the brain

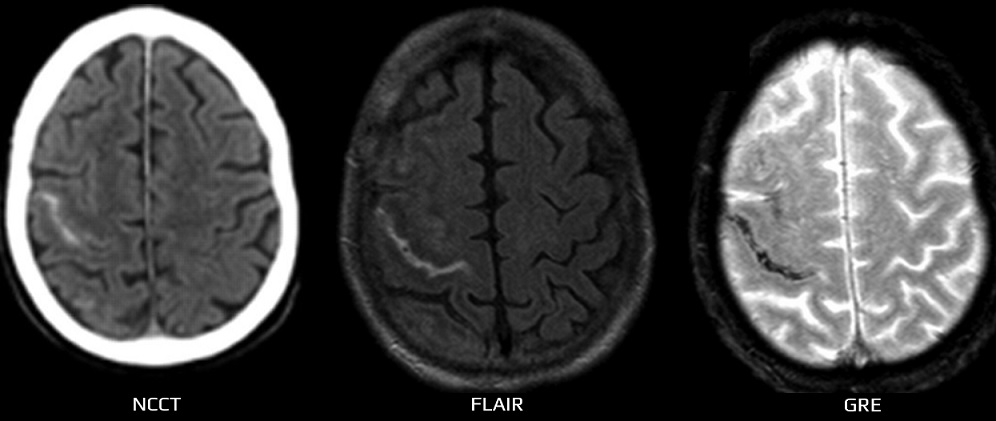

- no reaction in surrounding tissue, the lesion is hypointense on FLAIR (contains cerebrospinal fluid), DWI/ADC, and GRE are negative

- mostly asymptomatic; isolated cases with hydrocephalus, blepharospasm, etc., have been reported

- typical localizations:

- basal ganglia

- at the convexity

- mesencephalon-pons junction

- history of trauma is unreliable or negative in up to 50% of cases; there may be no external signs of injury

- in addition, it is often unclear whether the patient fell due to hemiparesis induced by the stroke or whether the stroke was caused by the fall (e.g., due to dissection, arterial rupture, etc.)

- if trauma is suspected, search for:

- don’t miss chronic SDH as it is isodense on CT in 1-3 weeks (look for signs of edema, add MRI if in doubt)

- traumatic changes (contusions):

- do not correlate with vascular territories

- are typically located in the temporal and frontobasal regions of the brain

- often have a hemorrhagic component and edema and may be associated with mild SAH

Psychosomatic disorders

|

- first episode of conversion disorder with a focal deficit (paresis, etc.) pose the biggest problem; the situation is easier with anxiety disorders

- a simplified classification can be made:

- panic attacks, anxiety

- conversion somatomorphic disorders

- simulation

- in the first attack, an organic cause must always be carefully excluded (negative imaging, incl. DWI)

- what to do during the clinical examination:

- assess the signs while distracting the patient’s attention (fluctuations in paresis severity can be observed)

- objectify the findings using EMG, EP, brain imaging

- look for discrepancies and fluctuations in motor impairment (e.g., rapid fall in Minagazzini in a walking patient, seeing a paretic patient walking in a hospital park, etc.)

- investigate the exact borders of hemihypesthesia (in psychosomatic disorders, the border is usually in the midline)

- search for the provoking moment and the potential benefit of the current condition (partner’s interest, financial motivation, etc.)

- note emotional inertia to severe deficits (e.g., a smiling patient who has suddenly “gone blind”)

- exclude rare Anton (denies blindness) and inverse Anton syndrome (patient sees but thinks he is blind)!

- look for psychiatric history

- clinical presentation

- in somatomorphic disorder or simulation, impaired mobility of one or more limbs, impaired hearing or blindness, and bizarre gait are not uncommon

- there is a long history of difficulties, repeated hospitalizations in different departments with negative findings

- vivid depiction of polymorphic difficulties, extensive documentation, keeping a diary of difficulties, etc.

- absence of pyramidal signs and atrophy of paretic limb, etc.

- purposeful, deliberate action for specific gain (e.g., compensation, pension, etc.)

- disorders in which physical symptoms are present without an obvious organic cause, have a presumed psychogenic cause and are not consciously produced or simulated

- mechanisms:

- reactivation of past emotions by a relatively recent provoking stressor

- reactions to a serious current trauma (e.g., rape, recent history of physical or psychological abuse)

- chronic suppression of anger followed by a series of frustrations in adulthood

- panic disorder with or without agoraphobia

- acute stress disorder

- post-traumatic stress disorder

- often accompanied by hyperventilation, strong feelings of fear (must be actively questioned), shortness of breath, palpitations

- the typical triggering factor usually occurs

- attacks tend to be uniform (typically paresthesias and dysesthesias, but there may also be motor manifestations)

- a trial with anxiolytics can be performed

Peripheral neurogenic lesions |

- usually can be distinguished by history, typical areal distribution of sensory and motor impairment, and usually present with pain

- a detailed neurological examination should distinguish peripheral from central symptoms

- small pre- or postcentral infarcts can be problematic, causing isolated motor or mixed deficits involving only specific muscle groups (e.g., cortical hand syndrome)

- may cause a problem in cases of sudden onset, e.g. due to infection or drugs, and with asymmetric presentation

- in particular, sudden onset of bulbar involvement with diplopia may raise suspicion of a vascular etiology, but if bilateral ptosis is present, it is more likely to be a manifestation of myasthenia gravis

- in the event of an acute diagnostic emergency, the effect of injectable neostigmine can be tested