ISCHEMIC STROKE / CLASSIFICATION AND ETIOLOGY

Moyamoya disease

Updated on 10/06/2024, published on 11/05/2023

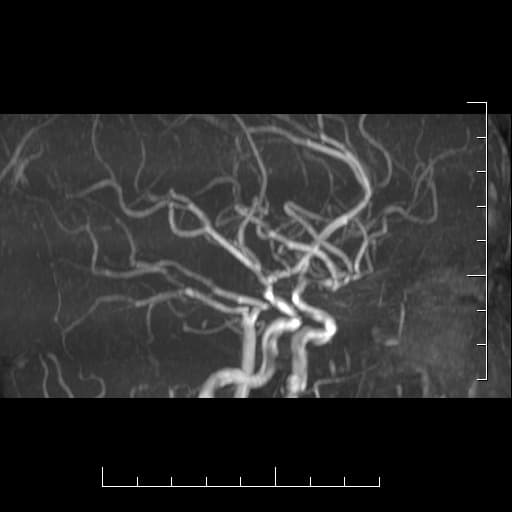

- progressive stenoocclusive disorder affecting the terminal segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA) and proximal segments of the arteries forming the circle of Willis (ACA, MCA, PCA)

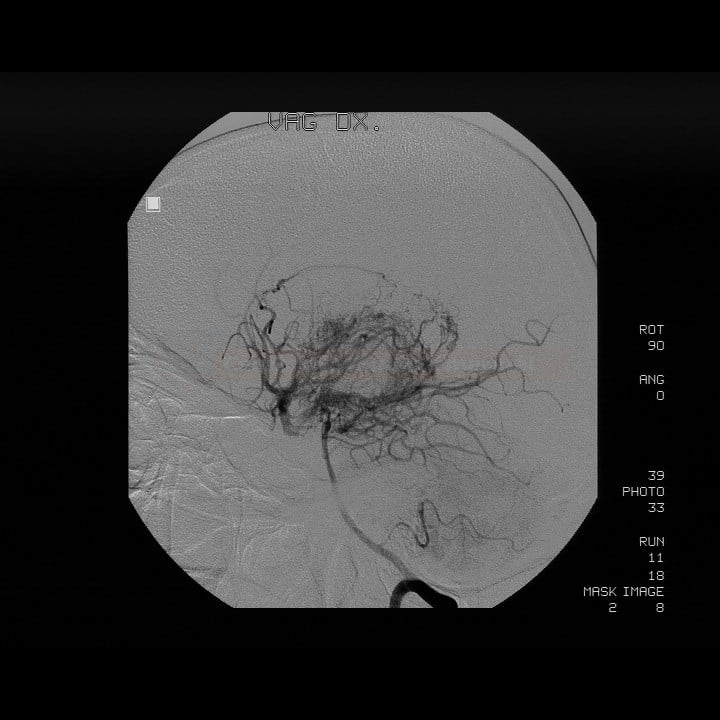

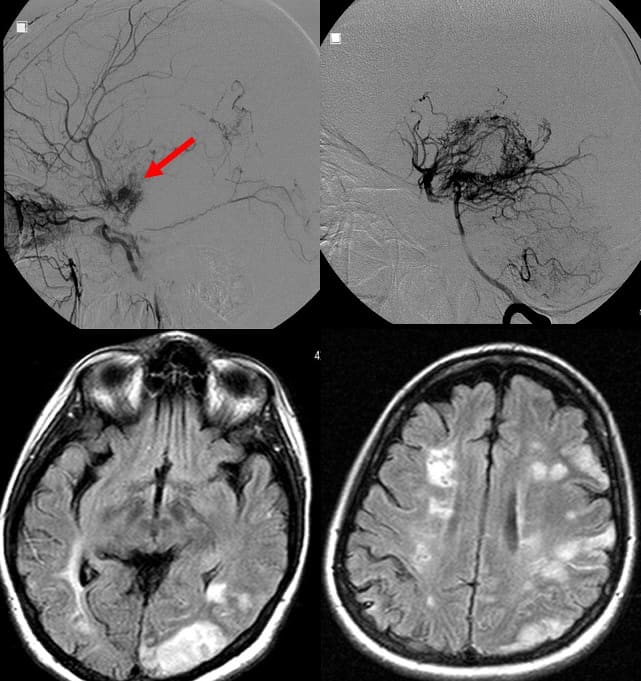

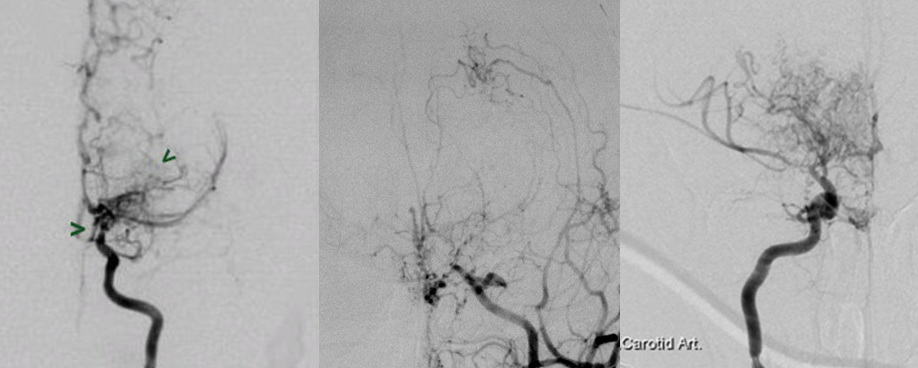

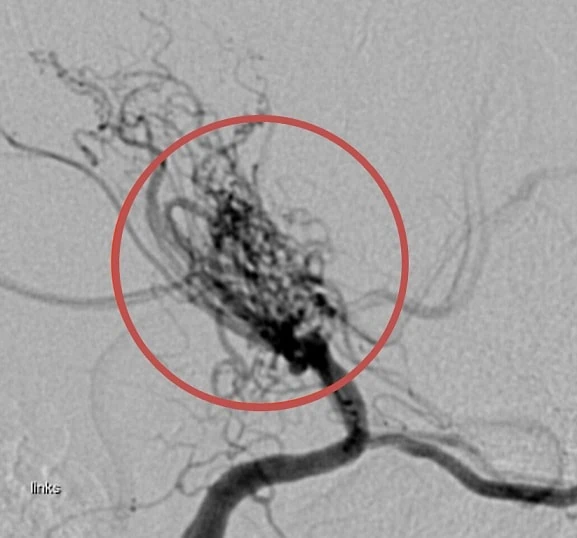

- an abnormal network of fine collateral arteries (lenticulostriate arteries, thalamic perforators, and pial arteries) is formed near stenotic vessels, resembling smoke puffs (moya-moya)

- the process is usually bilateral, but unilateral manifestation does not exclude the diagnosis

Etiology

- moyamoya angiopathy (moyamoya pattern) may be caused by a variety of congenital and acquired diseases (see table)

- proliferation and thickening of the intima of the terminal ICA segment and proximal MCA segment predominate; the proliferating intima may contain lipid deposits, but there is no evidence of inflammation [Bang, 2015]

- thrombi may be present

- associated neovascularization occurs as a compensatory mechanism (collateral circulation)

- in practice, moyamoya should be considered more as a radiologic entity that can be associated with several diseases

- acquired (e.g., moyamoya syndrome in vasculitis) – see table

- congenital – sporadic and familial forms (10% are reported, but the number is probably higher)

- AD transmission with low penetrance has been demonstrated in familial cases of MMD with linkage to chromosomes 3,6,8,12 and 17 (e.g., 17q25.3 Raptor); Ring finger 213 (RNF213) appears to be an important gene, its exact function is unknown [Bang, 2015]

- the moyamoya pattern may be caused by other inherited vasculopathies (Grange syndrome, ACTA2 mutations, etc.)

| Moyamoya disease |

|

| Moyamoya syndrome – acquired conditions |

|

Epidemiology

- predominantly in Asians, with the highest prevalence in Japan (3.16 cases/100,000 inhabitants)

- rarely affects Caucasians, African Americans, and Hispanics

- peak incidence around age 4 (2/3) and then at age 30-40 (1/3)

- approx. 10% of cases are familial (inherited)

Clinical presentation

- onset of symptoms occurs across a wide age range (4 months to 67 years), peaking in the 1st and 3-4th decade of life

- the clinical course is variable, ranging from asymptomatic forms to TIAs or strokes with permanent neurological deficit

- in children, common symptoms include mono- or hemiparesis, sensory disturbances, involuntary movements, headache, cognitive impairment, and epileptic seizures; intracerebral bleeding is relatively rare

- in adults, intraventricular, subarachnoid, or intraparenchymal bleeding is more common (up to 30% of cases)

- hematomas most commonly result from ruptured collaterals [Kim, 2017]

- watershed infarcts are common

- clinical presentation, especially the incidence of bleeding, is influenced by racial factors, with a higher prevalence of bleeding observed in Asians compared to Caucasians

Diagnostic evaluation

Diagnostic criteria

| Radiological and histological diagnostic criteria for MMD |

|

| Angiographic findings suggesting the diagnosis of moyamoya | |

|

|

|

Histopathologic findings suggesting the diagnosis of moyamoya

|

|

|

|

Moyamoya disease staging [Suzuki 1969]

|

|

|

Stage 1 – narrowing of the carotid bifurcation

Stage 2 – formation of collaterals (“moyamoya arteries”), stenosis of the terminal ICA, dilatation of the MCA and ACA

Stage 3 – intensive formation of moyamoya arteries, progression of stenoses of ICA, MCA, and ACA

Stage 4 – gradual disappearance of moyamoya arteries, the disappearance of PCA, further narrowing of ICA, MCA, and ACA

Stage 5 – a further reduction of moyamoya arteries with occlusion of ICA, ACA, and MCA

Stage 6 – ICA essentially disappears; the brain is supplied by the ECA

|

- the staging system, initially described by Suzuki and Takaku in 1969, is still used

- staging is based on DSA findings, although a similar system may be applied to MRA or CTA

- disease progression is more rapid in children compared to adolescents or adults

Imaging modalities

- digital subtraction angiography (DSA) – the gold standard, practically replaced by MRA/CTA

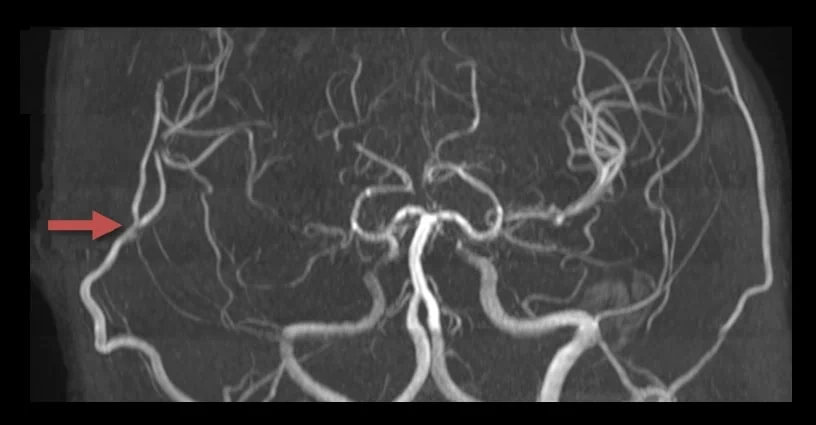

- MR+MRA / CT+CTA

- parenchymal lesions

- typically watershed or territorial infarcts

- hemorrhages or asymptomatic microbleeds (GRE/SWI sequences)

- cerebral atrophy

- evidence of stenoses in typical locations (distal ICA, M1, or PCA) + a characteristic collateral network

- unilateral finding is observed in up to 18%

- vessel wall imaging can help in DDx (from atherosclerosis or inflammation)

- concentric stenosis

- minimal or absent enhancement

- homogeneous T2 signal

- absence of atherosclerotic changes

- detection of collaterals

- perforator network (puff of smoke) is mainly visualized on DSA (to a lesser extent on CTA or MRA)

- Ivy sign – increased signal intensity on MR FLAIR and T1C+ in the leptomeninges and perivascular spaces – indicates slow or retrograde flow in the leptomeningeal and cortical arteries

[Ohta, 1995] [Tharayil, 2019]

- parenchymal lesions

- neurosonology

- the flow in the affected and distal segments + vasomotor reactivity (CVR) may be monitored ⇒ may help to indicate surgical treatment

Genetic testing

- mutations testing in the RNF213 gene located on 17q25 (in Asians) → see here

- experts suggest against systematic variant screening of RNF213 (ESO guidelines, 2023)

- “moyamoya panel” in the differential diagnosis (incl. ACTA2, Grange sy, etc.)

Hemodynamic assessement

- hemodynamic assessment (by CT, MRI, SPECT, PET, and ultrasound) is suggested for all patients with MMA (ESO guidelines, 2023, consensus)

- imaging methods most familiar and available, depending on individual institutions, should be used

Differential diagnosis

- moyamoya syndrome (see the table above) must be distinguished

Management

Surgery

- always consider the risk/benefit when evaluating treatment options

- surgical treatment is mainly indicated in patients with a progressive, symptomatic course

- the primary aim is to improve flow and prevent further formation of fragile collaterals

- surgical treatment is mainly indicated in patients with a progressive, symptomatic course

- no clinical study comparing the effect of conservative and surgical treatment is available

- the JAM trial showed marginal benefit in preventing rebleeding

- several small-scale studies have produced conflicting results

- revascularization recommendations (ESO 2023):

- adult patients:

- adult patients with hemorrhagic presentation: surgery (evidence only for direct STA-MCA bypass) in case of cerebral hemodynamic impairment

- adult patients with ischemic presentation: revascularization should be considered in case of clinical symptoms and/or imaging markers of hemodynamic impairment (uncertain risk/benefit)

- asymptomatic adult patients: consider conservative treatment except in patients with both cerebral hemodynamic impairment and silent ischaemic lesions

- pediatric patients:

- suggest revascularization surgery if there is evidence of ongoing ischemic symptoms or cerebral hemodynamic impairment; except in case of large territorial ischemic lesion

- there is continuous uncertainty over the risks and benefits of cerebral revascularization

- adult patients:

- surgical revascularization should be performed in a referral center and by a neurosurgeon with significant experience in surgical revascularization techniques

- according to a meta-analysis, better outcomes can be expected with direct and combined anastomosis compared to indirect anastomosis alone (Nguyen, 2022)

- direct/combined revascularization is suggested instead of indirect strategies for reducing the risk of stroke (ESO guidelines, 2023)

- in pediatric patients, a combined revascularization instead of indirect strategies is suggested whenever technically possible to decrease the short-term risk of stroke

- moya-moya syndrome with potential causal treatment (e.g., vasculitis) should be excluded before proceeding with surgery [Fujimura, 2015]

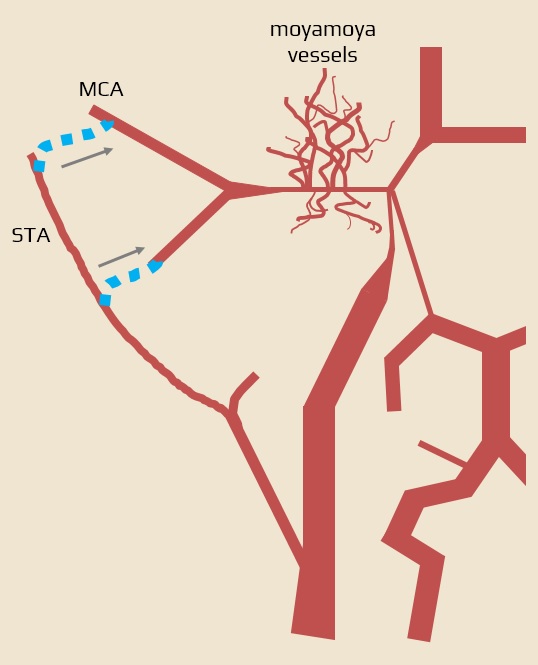

- direct anastomosis between the superficial temporal artery (STA) and the middle cerebral artery (MCA) – STA-MCA anastomosis [Golby, 1999]

- vessel-to-vessel anastomosis offers immediate revascularization (convenient when symptoms are progressive)

- a recipient vessel size of > 1-1.5 mm is required

- problematic in pediatric cases

- indirect anastomosis (flow improvement can be expected within weeks because a new capillary network is built; feasible in children)

- encephalo-duro-arterio-synangiosis (EDAS)

- encephalo-duro-arterio-myo-synangiosis (EDAMS)

- pial synangiosis

- combined anastomosis (direct + indirect)

Conservative therapy

- there is no specific drug therapy to alter the course of the disease

- standard treatment protocols for ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes are applied

- efficacy and safety of thrombolysis is unclear; increased risk of bleeding from fragile collaterals needs to be considered

- efficacy and safety of thrombolysis is unclear; increased risk of bleeding from fragile collaterals needs to be considered

- for secondary stroke prevention, antiplatelet therapy is commonly used

- not an evidence-based approach; should be individualized, taking into account the type and severity of the stroke, angiographic findings, and a risk-benefit analysis of the therapy

- antiplatelet therapy is also accepted by the AHA/ASA Guidelines 2021 (2b/C-LD) and ESO guidelines 2023 (expert opinion)

- bleeding is common in Asians, complicating the use of antithrombotic agents

- not an evidence-based approach; should be individualized, taking into account the type and severity of the stroke, angiographic findings, and a risk-benefit analysis of the therapy

- the role of antiplatelet therapy in primary stroke prevention is unclear

- long term ASA is suggested (ESO guidelines 2023, expert opinion)

Prognosis

- prognostic factors

- rate and extent of vascular occlusions

- patient’s ability to form functional collateral circulation

- age

- neurologic deficit severity

- extent of cerebral infarction

- some patients remain stable without surgical intervention; sometimes, they stabilize after severe cerebral infarction or hemorrhage with a permanent disability

- approx. 50-60% of patients exhibit cognitive impairment due to multiinfarct dementia

- mortality rate ~10% in adults and ~4-5% in pediatric patients

- the most common cause of death is intracranial hemorrhage

![Enlarged intima (black arrow) and intraluminal thrombus (blue arrow) in moyamoya [Scott, 2009]. Enlarged intima (black arrow) and intraluminal thrombus (blue arrow) in moyamoya [Scott, 2009]](https://www.stroke-manual.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/moyamoya_histology.jpg)