ISCHEMIC STROKE / PREVENTION

Carotid endarterectomy (CEA)

Updated on 15/07/2024, published on 31/01/2023

- carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is the gold standard for treating significant carotid artery stenosis (both symptomatic and asymptomatic)

- randomized trials have confirmed that CEA is more effective than conservative treatment:

- symptomatic stenosis (NASCET, ECST, joint data analysis of ACTS, NASCET, and VA trials)

- surgery was associated with harm in patients with carotid stenosis < 30% and no effect was seen in patients with 30–49% stenosis

- the marginal benefit was found in those with 50–69% stenosis, and CEA was highly beneficial in those with stenosis ≥ 70%, provided that there was no near-occlusion (Rothwell, 2003)

- asymptomatic stenosis (ACAS, ACST, ACST-2, CREST)

- symptomatic stenosis (NASCET, ECST, joint data analysis of ACTS, NASCET, and VA trials)

- randomized trials have confirmed that CEA is more effective than conservative treatment:

- an alternative to CEA is carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS)

- the long-term effects of both procedures are similar (the annual risk of ipsilateral stroke is ~ 0.6 and 0.64%, respectively); periprocedural complications are higher with CAS [Brott, 2019]

- CEA seems to be a better option in patients aged ≥ 70 years, while both procedures have comparable outcomes in younger patients [Müller, 2020] (AHA/ASA 2021 2a/B-R)

- the benefit of transcarotid revascularization (TCAR) is unclear (AHA/ASA 2021 2b/B-NR)

- the decision to revascularize should be made by a team that includes a neurologist, neurosurgeon/vascular surgeon, and/or interventional radiologist

Indications

Acute symptomatic carotid occlusion

- consider IVT or MT → Recanalization therapy for acute stroke

- emergent CEA

- patients ineligible for standard recanalization procedures

- patients with mild deficits and small ischemia at acute risk of hypoperfusion; efficacy is not proven (AHA/ASA 2018 IIb/B-NR)

- CEA indication is supported by the absence of intracranial occlusion (which is suitable for combined endovascular procedure), low flow in MCA on TCD/TCCD, and/or significant MR DWI/PWI mismatch

- ICA occlusion in the absence of intracranial occlusion is not suitable for endovascular treatment due to the high risk of periprocedural distal embolization

- acute surgical revision may be necessary for cases of post-procedural acute ICA thrombosis (intracranial embolization must be excluded)

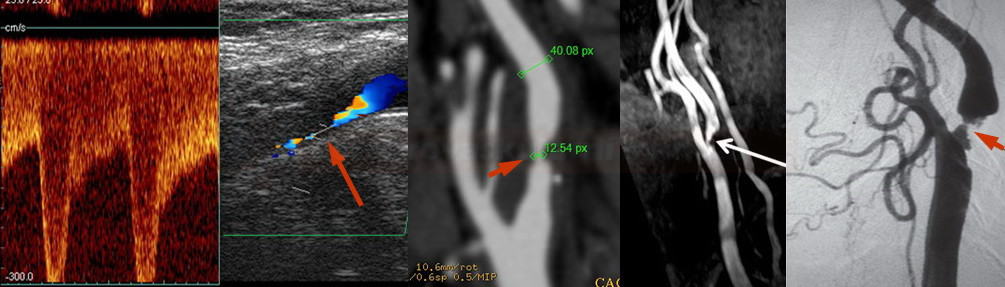

- imaging of carotid occlusion is discussed here

Symptomatic carotid stenosis

- the risk of ischemic stroke or vascular death in symptomatic carotid stenosis >70% is up to 26% over the next 2 years

- risk of stroke depends on symptomatology, sex, and severity of stenosis

- one-year risk of stroke increases to 34% for stenoses 90-94%, then decreases to 11% for subtotal stenoses [Morgenstern, 1997]

- CEA is performed to prevent further ischemic events

- CEA is indicated in patients with stenosis > 50% when another more likely cause has been excluded

- CEA should be performed in all symptomatic patients with mRS 0-2, timing: 2-14 days after stroke (AHA/ASA 2021 2a/C-LD)

- symptomatic ICA stenosis 70-99% detected by non-invasive method, 30-day perioperative M/M < 6% is required (AHA/ASA 2021 I/A)

- symptomatic stenosis 50-70% verified by CTA/MRA with 30-day perioperative M/M < 6% (AHA/ASA 2021 I/B-R)

- occlusion/significant stenosis of the contralateral ICA is not a contraindication to CEA but carries a higher perioperative risk (approximately 2-fold). According to NASCET, the 2-year risk of stroke is 22% (CEA) vs. 67% (medical therapy) for symptomatic stenosis with contralateral occlusion – ARR 45%/2 years [Barnett,2002]

- stenoses < 50% are generally not recommended for CEA (AHA/ASA 2021 3/A)

- borderline stenosis may be considered for surgery in the following situations: evidence of a high-risk plaque (ulceration, intraplaque bleeding, thrombosis) + recurrent episodes despite best medical therapy (of course, other more likely causes must be excluded)

Asymptomatic carotid stenosis

Symptomatic carotid stenosis – specific situations

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

Timing

- the earlier CEA is performed and the more severe the stenosis, the greater the reduction in the risk of stroke recurrence

- the benefit of surgery is highest within 2 weeks after stroke

- NASCET – the absolute risk reduction (ARR) of CEA performed within 2 weeks after stroke was up to 30%; within 4-12 weeks, it was only 12%

[Rothwell, 2008

- NASCET – the absolute risk reduction (ARR) of CEA performed within 2 weeks after stroke was up to 30%; within 4-12 weeks, it was only 12%

|

Emergent CEA

(minutes – hours) |

|

|

Early CEA

(< 14 days) |

|

| Delayed CEA (4-6 weeks) |

|

|

Elective CEA

|

|

The severity of neurological deficit

- for patients who have had a TIA/minor stroke, perform early CEA within 3-7 days (AHA/ASA 2018 IIa/B-NR)

- early CEA is safe in patients with TIA/minor stroke [Tsivgoulis, 2014]

- CEA can be safely performed several days after IV thrombolysis [Ijäs, 2018] [Smith, 2014]

- emergent CEA (as a treatment option) can be considered in a selected group of patients → see here

- ultra-early prophylactic CEA (<2 days) seems to be associated with a higher perioperative risk of stroke (a longer interval may allow the onset of action of antiplatelet and statin therapy with stabilization of plaque or thrombus. At the same time, there is also a higher risk of hyperperfusion syndrome [Ijäs, 2018] [Kennedy, 2012]

- CEA performed > 2 years after the stroke no longer provides any benefit over medical therapy

- wait ~3-6 weeks in patients with moderate deficits and ischemia

- indication for CEA is questionable in patients with severe deficits or extensive ischemia

Ischemic lesion characteristics

- the risk of hemorrhagic transformation increases with the presence of infarcted tissue; both the size and location of the ischemia are important factors

- the risk of bleeding increases with the size of the ischemia and is higher for MCA territory stroke due to increased blood flow after CEA

- the safe size is unknown; some experts suggest early CEA for ischemia < 2 cm in diameter

- for larger ischemia (> 2cm) or moderate deficits, it is recommended to delay CEA for 3-6 weeks

- timing is unclear for small spontaneous hemorrhagic infarctions (HI type 1); it is better to wait until the blood is resorbed due to heparinization during CEA

- for larger bleeding (HI2 and any PH), a longer interval is advised

Arrangements before surgery

- assess carotid stenosis – usually, neurosonology in combination with CTA (or MRA) is used; DSA is less common

- severity of stenosis and its etiology

- high-risk plaque characteristics?

- collateral circulation and contralateral ICA status?

→ Measurement of stenosis on CTA (according to NASCET)

→ Quantification of stenosis by ultrasound

→ Assessment of intracranial flow, including cerebral vasomotor reactivity

→ Classification of atherosclerotic plaques

- consider the ischemic lesion characteristics on imaging (CT/MR) and neurological deficit (incl. NIHSS)

- is the stenosis symptomatic or asymptomatic?

- recent or older infarct?

- what is its extent?

- is it relevant to carotid stenosis?

- is there a hemorrhagic component?

- review the patient´s history and perform a preoperative physical examination (myocardial infarction is the most common cause of death after CEA and the most common non-neurological complication)

- physical examination

- ECG

- TTE

- coronarography or TEE in selected cases

- proper correction of hypertension in the perioperative period is critical (to reduce the risk of hyperperfusion syndrome)

- do not interrupt antiplatelet and statin therapy ( (the effect is mainly seen in symptomatic stenoses) (AHA/ASA I/A)

- all patients scheduled for carotid surgery should receive 81-325 mg of aspirin or 75 mg of clopidogrel daily; this therapy should continue lifelong (AHA/ASA 2011 I/A)

- the ACE (ASA and Carotid Endarterectomy Trial) tested ASA at doses 81 mg, 325 mg, 650 mg, or 1300 mg

- n= 2849 patients

- therapy was started before CEA and continued for three months after the procedure

- 81-325mg of ASA reduced the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and death more effectively than ASA at doses 650 and 1300 mg

- the ACE trial remains the only randomized, double-blind trial of perioperative antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing CEA. Such a study is lacking for clopidogrel and other antiplatelet agents

- dual antiplatelet therapy (ASA+CLP), as well as clopidogrel alone, is associated with an increased incidence of perioperative wound hematoma compared to aspirin but on an acceptable low level of incidence

- perioperative bleeding: ASA 11.7%, CLP 20.4%, ASA+CLP 24.1% [Oldag, 2012)

- severe space-occupying hematoma needing operative re-exploration: ASA+CLP 3.6 %, CLP 4.3 %, ASA 1.2 % [Oldag, 2012)

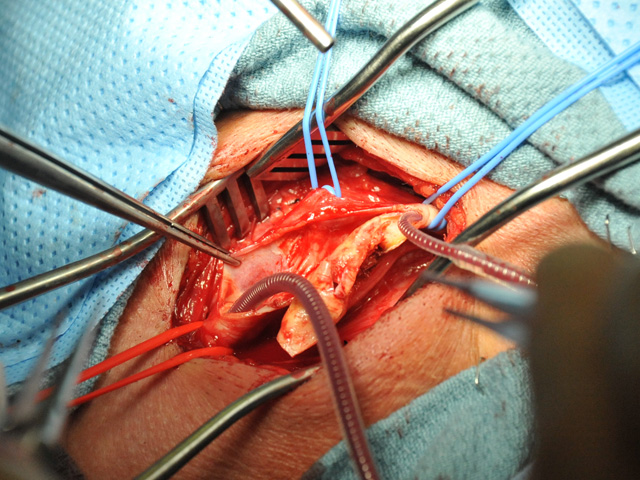

Procedure and post-procedural care

- surgery can be performed under local (LA) or general anesthesia (GA)

- the choice of anesthesia does not affect the outcome (GALA trial)

- neuromonitoring (SSEP, TCD) is beneficial during GA

- the choice is based on the patient, surgeon, or anesthesiologist’s preference

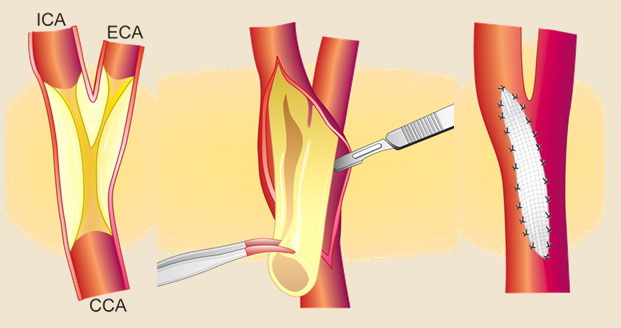

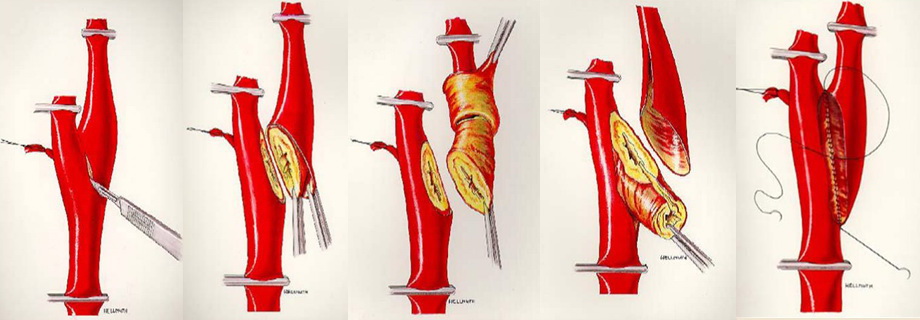

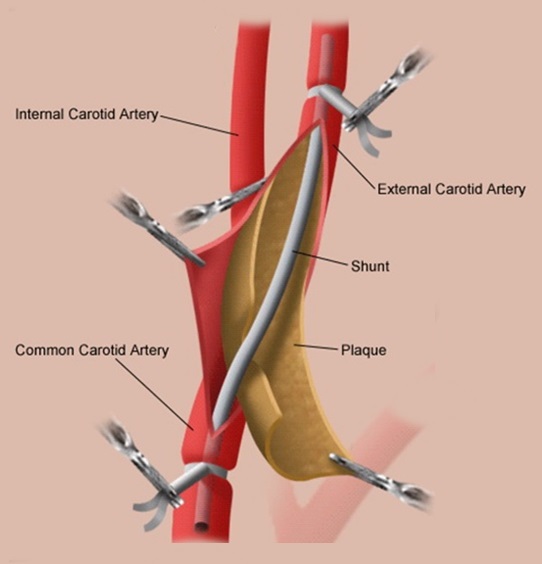

- the incision and arteriotomy are longitudinal or transverse (eversion CEA)

- heparinization is used before clamping the artery

- use a temporary shunt to maintain adequate blood flow to the brain in the following situations:

- impaired consciousness after carotid clamping / impaired neuromonitoring parameters during GA

- known contralateral ICA occlusion, poor collateral circulation

- patch x direct suture

- patches are reported to have a lower risk of restenosis [Malas, 2015]

- patches are reported to have a lower risk of restenosis [Malas, 2015]

- heparin is neutralized after surgery is completed

- the patient is transferred to the ICU for monitoring of vital signs

- ensure strict BP control (<150/100mm Hg) to prevent hyperperfusion syndrome

- regularly monitor neurostatus and surgical wound (bleeding, infection, etc.)

Complications

- the risk of complications during and after a surgical procedure depends on several factors:

- correct indication and timing of the procedure

- quality of preprocedural care (statins, antiplatelet therapy, optimal BP management, etc.)

- the experience and skill of the surgical team and the level of postoperative care

- increased perioperative risk is associated with the following conditions:

- unstable neurological status (evolving or fluctuating lesions)

- manifestation of multiple vascular lesions

- occlusion of the contralateral ICA or CCA (RR 1.91)

- tandem intracranial stenosis (RR 1.56)

- intraluminal thrombus

- female sex, advanced age (RR 1.36 in patients over 75 years)

- coronary heart disease

- history of heart failure

- chronic pulmonary disease (most commonly obstructive disease)

- arterial hypertension (RR 1.82)

- atherosclerotic peripheral artery disease (PAD); RR 2.19

| CEA-related complications |

| I. Central and general |

|

| II. Peripheral |

|

Local thrombosis/distal embolization

- a significant and feared cause of 30-day mortality/morbidity

- thrombolysis is contraindicated because of recent surgery

- if only the extracranial portion of the ICA is thrombosed, surgical revision with thrombectomy is indicated

- for symptomatic distal embolization (with or without extracranial thrombosis), perform endovascular mechanical recanalization

- both extra- and intracranial thrombosis can be treated simultaneously

- consider stenting if postoperative dissection with occlusion or hemodynamically significant stenosis and signs of hypoperfusion are detected

Hyperperfusion syndrome → more here

Cranial nerve injury → more here

- incidence 5-27 %

- damage usually occurs due to traction and tension during manipulation in the surgical field or due to compression of the hematoma

- risk factors: emergency procedures, acute revisions for hematoma, surgery for restenosis, etc.

- treatment is generally conservative, functional improvement usually occurs within 6-12 months after CEA in ~ 88% of cases

- the hypoglossal nerve (most commonly affected nerve) → atrophy of the ipsilateral half of the tongue, difficulties with articulation, chewing, and swallowing

- marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve → uncommon complication (1-2%), but symptoms can mimic central facial palsy (lower portion is affected) (Günes, 2021)

- branches of the vagus nerve (such as the recurrent laryngeal nerve or superior laryngeal nerve) → dysphonia

- glossopharyngeal nerve → dysphagia

Restenosis

- definitions vary; usually, it is defined as a newly detected stenosis > 50-60%

- ~6% in the first year [Goodney 2010]

- 10-15% /5 years (variable data has been reported)

- classification

- early (intimal hyperplasia) in < 2-3 years

- late (atherosclerosis) after 3 years

- irregular plaques have an increased risk of distal embolization

- risk factors

- age < 65 years

- smoking

- female gender

- elevated creatinine (early)

- elevated cholesterol (late)

- elevated CRP

- management

- strict management of vascular risk factors

- repeated CEA or CAS is reserved for progressive stenosis > 70-80% (rules are the same as for the primary indication of asymptomatic stenosis)

Follow-up

- it is recommended to perform an ultrasound examination at 1, (3) and 6 months after surgery to detect early restenosis

- according to AHA/ASA 2014, routine follow-up is not necessary (cost-benefit)

- however, in clinical practice, annual ultrasound follow-up is quite common

- follow-up visits in the vascular clinic are recommended; these should include comprehensive secondary prevention measures