ISCHEMIC STROKE / CLASSIFICATION AND ETIOLOGY

Inherited thrombophilia and ischemic stroke

Updated on 07/11/2023, published on 02/05/2023

Thrombosis is the process of forming a blood clot (thrombus) inside veins or arteries

-

venous thrombosis – characterized by reduced blood flow (stasis) and hypercoagulability (which happens when plasma clotting factors are activated and their inhibitors fail)

-

deep vein thrombosis may be complicated by pulmonary embolism

-

-

arterial thrombosis – caused by platelet activation and aggregation along with endothelial dysfunction (most commonly caused by atherosclerosis)

- differentiate thrombi from cardiac cavities (cardioembolism) and those from peripheral veins reaching the cerebral circulation via paradoxical embolization)

Thrombophilia definition

- thrombophilia (hypercoagulable state) is part of Virchow´s triad

- it is associated with an increased propensity to thrombus formation (congenital, acquired), most commonly in veins

- approx. 5-8% of the population carry some thrombophilic mutation

- the incidence of inherited thrombophilia in patients with ischemic stroke is similar to that in the healthy population [Hankey, 2001]

- approx. 5-8% of the population carry some thrombophilic mutation

- inherited thrombophilia will be discussed here; an overview of all hematologic disorders associated with stroke can be found here

- clinical manifestation occurs mainly in homozygous forms; heterozygous forms require additional risk factors to manifest

- vascular risk factors

- immobilization/perioperative conditions

- pregnancy and puerperium/oral contraception (OC)/hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

- for example, Leiden mutation heterozygotes have a 5-10 times higher relative risk of thrombotic complications; use of OC or HRT increases this risk up to 35 times compared to a healthy population, and the risk can be up to 100 times higher in the presence of other concomitant mutations (factor II, MTHFR)

- infection/sepsis

- malignancy, etc.

Thrombophilia and arterial stroke

- thrombophilic disorders most commonly manifest with venous thrombosis

- the association with arterial stroke is uncertain (associated with intraarterial thrombus formation); mere coincidence is common [Juul, 2202] [Hankey, 2001]

- thrombophilia may cause an ischemic stroke by:

- paradoxical embolization of venous thrombi via PFO [Hamedani, 2010]

- formation of thrombi in the cardiac cavities, valves, or PFO channel

- the benefit of screening for thrombophilic mutations in stroke patients is unknown

| When a hypercoagulable condition should be considered? |

|

Classification

| Basic mechanisms contributing to stroke development in thrombophilia |

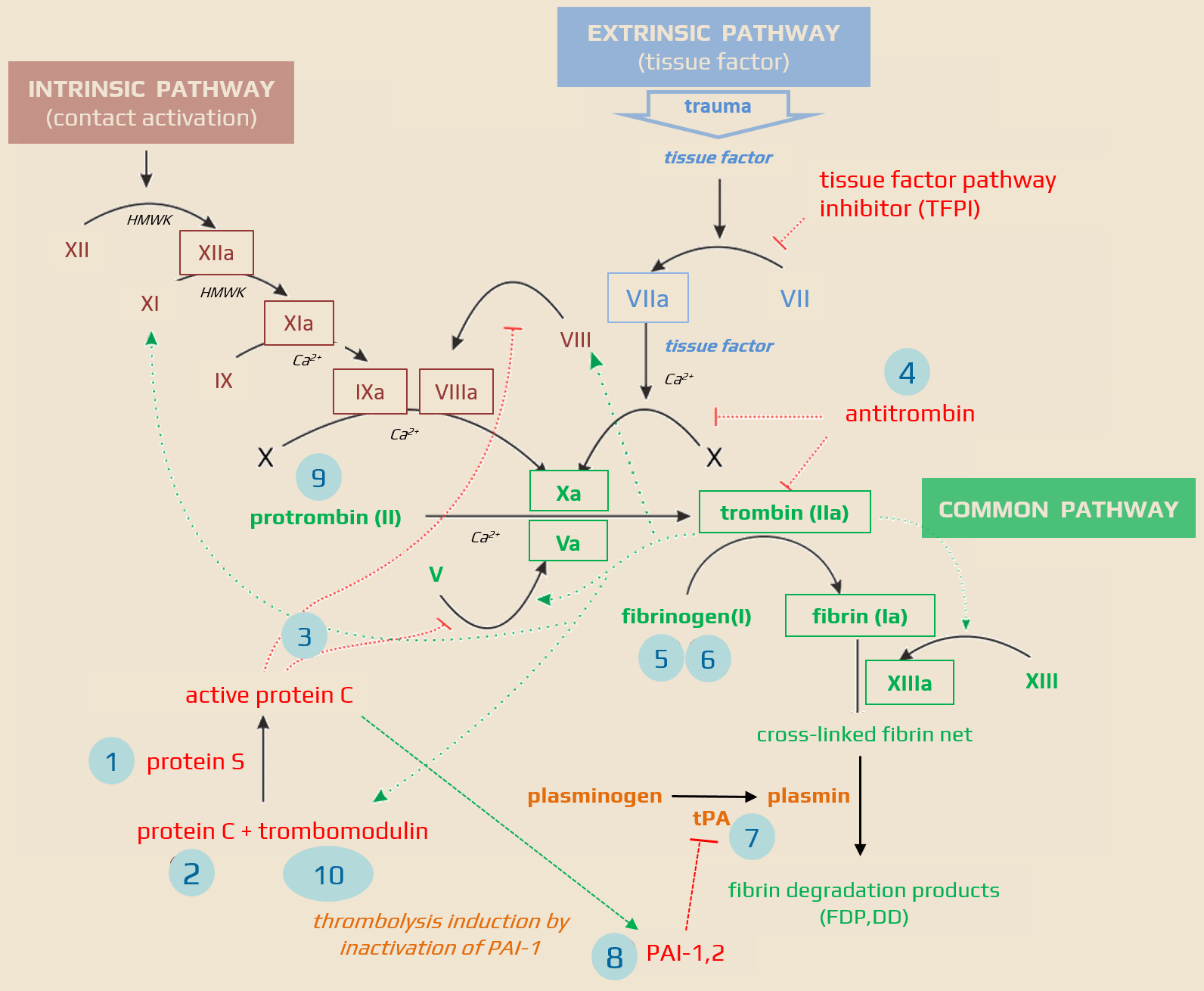

| Anticoagulant factor deficiency (AT III, PC, and PS) Elevated concentrations of coagulation factors (typically V and VII) Decreased fibrinolytic activity (plasminogen deficiency and inhibition of plasminogen activator) |

Classification according to the etiology of the hematologic disorder

| Congenital disorders | Acquired disorders |

|

Hereditary thrombophilia

1. protein S deficiency Hemoglobinopathy

|

|

Classification based on the likelihood of causal association with stroke

| Hematologic disorder | Possible or probable association with stroke | Association uncertain |

| Hereditary coagulopathies (coagulation-inhibiting factor deficiency) |

antithrombin III deficiency protein C deficiency APC resistance (Leiden) |

protein S deficiency heparin cofactor II deficiency factor II (prothrombin) mutation |

| Hereditary fibrinolysis disorders | dysfibrinogenemia hyperfibrinogenemia |

plasminogen deficiency plasminogen activator deficiency factor XII deficiency prekallikrein deficiency excess of PAI-1 |

| Increased concentrations of coagulation factors | factor IX factor XI Thrombin Activatable Fibrinolysis Inhibitor (TAFI) |

|

| Autoimmune diseases |

antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) |

|

| Erythrocyte disorders | polycythemia vera sickle cell disease (hemoglobinopathy) |

secondary polycythemia paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria thalassemia |

| Platelet disorders |

essential thrombocythemia thrombocythemia in myeloproliferative diseases Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) |

secondary thrombocythemia acquired platelet hyperaggregability (“sticky” platelets) |

| Other prothrombotic conditions with uncertain or multifactorial association with the occurrence of ischemic stroke |

|

Diagnostic evaluation

Overview of inherited hypercoagulable disorders

- the terms activated protein C resistance (APCR) and Leiden factor V mutation are often confused

- the Leiden mutation (substitution of AK arginine for glycine at codon 506) is one of the mutations leading to APC resistance; this mutation is the most prevalent and makes activated factor V resistant to the activated protein C and S complex

- the risk of a first DVT increases by roughly 5-8 times in heterozygous Leiden mutation carriers, but the risk is multiplied in combination with other prothrombogenic conditions

- it is the most common congenital thrombophilia in the European population, with a frequency of 5-8%

- the mutation is present in approx. 20% of patients with DVT; in a selected population under 50 years old, it is up to 40%

- in combination with OC ( which alone increases the risk of DVT by about 3-4 times), the relative risk of a first DVT increases up to 50 times! ⇒ consider another form of contraception

- the rare homozygous mutation increases the risk of first DVT by about 50-80 times; the risk increases when combined with other thrombophilic conditions

- the significance of the mutation lies in its prevalence in the general population and potential interaction with other prothrombogenic conditions, such as the use of oral contraceptives (OC) or hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

- asymptomatic heterozygous Leiden mutation carriers should be watched during pregnancy; anticoagulation should be initiated at a prophylactic dose (with a temporary full dose after delivery) in the presence of additional risk factors

- patients should receive warfarin for 6-12 months after isolated DVT (level 1A recommendation); in individual cases, long-term anticoagulation may be advised (level 2C)

| Acquired causes of APCR |

|

- antithrombin is essential for the inactivation of thrombin and is one of the most potent inhibitors of coagulation

- there are two types of antithrombin deficiency

- type I – reduced antithrombin plasma concentration and function

- type II – reduced function at normal levels

- incidence in the unselected population is relatively rare (0.02-0.1%)

- acquired antithrombin deficiency is associated with:

- heparinization

- liver disease

- nephrotic syndrome

- responsible for approx. 1.1-4.3% of venous thromboses

- RR of DVT ~ 25 times higher compared to the control population

- RR of recurrent DVT ~ 1.5-3 times higher compared to DVT patients without antithrombin deficiency

- some authors advocate long-term warfarin treatment after the initial idiopathic DVT

- the ACCP expert panel recommends anticoagulation for 6-12 months (level 1A recommendation) and consideration of long-term anticoagulation therapy (level 2C)

- protein C, after activation by the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex and binding of protein S cofactor, degrades activated factors V and VIII and stopping the thrombin production

- protein C deficiency

- type I – low levels of protein C

- type II – normal levels of dysfunctional protein C

- deficiency is congenital or acquired

- congenital protein C deficiency is a relatively rare group of disorders (more than 160 different mutations have been described); heterozygous form occurs in 0.02-0.04% of the normal population, but in patients with a history of DVT in approx. 4%

- acquired causes of protein C deficiency are the same as for protein S (except for pregnancy and oral contraception)

- as with protein S, the homozygous form is associated with severe thrombotic complications in the early postnatal period

- protein S and C levels should tested in the absence of warfarin treatment (vitamin K-dependent factors)

- in clinical practice, long-term anticoagulant therapy should be considered in patients with a single episode of idiopathic DVT and protein C/S deficiency

- in pregnancy, patients with protein C or S deficiency without a history of DVT can only be observed

- if other risk factors are present (e.g., age > 30 years, additional thrombophilia, or immobility), LMWH should be administered prophylactically

- the effect of LMWH should be monitored at regular intervals

- protein S is a cofactor of activated protein C (APC) that regulates the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin

- a rare heterogeneous group of disorders (more than 130 different gene mutations have been reported)

- incidence:

- 0.01-0.1 % in the general population

- 2.3-4.6% in DVT patients

- RR of DVT is up to 10 times higher in asymptomatic individuals than in the general population

- RR of recurrent DVT ~1.5-3 times higher

| Acquired causes of protein S deficiency |

|

- the second most common congenital thrombophilia caused by the substitution of glutamine for arginine at nucleotide position 20210

- the defect leads to higher concentrations of Factor II (prothrombin), which increases the risk of thrombosis

- it is unknown whether having this mutation increases the risk of DVT recurrence; the isolated heterozygous mutation is unlikely to affect DVT recurrence

- recommendations for the duration of anticoagulation therapy and prevention of thromboembolism in pregnancy are the same as for the heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation

- in case of a combination of ≥ 2 mutations, the risk of DVT recurrence is already 2-5-fold

- anticoagulant therapy for 12 months is advised

- long-term anticoagulant therapy may be considered

- elevated factor VIII level seems to be the most significant

- activity of > 150% increases the relative risk of DVT up to 5-fold

- risk of arterial thrombosis is also slightly increased (Kamphuisen,2001]

- equally significant is an elevated level of fibrinogen, which increases the risk of DVT by 4 times

- independent risk factor for MI and stroke

- the majority of tPA circulates as an inactivated complex with a plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1)

- decreased tPA levels are associated with reduced fibrinolytic activity and promotion of atherosclerosis

- hyperhomocysteinemia is a metabolic syndrome caused by the interaction of genetic and exogenous factors and is associated with several medical conditions:

- methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutations (MTHFR – e.g., 677TT)

- vitamin B6,12, folate deficiency

- increased intake of methionine (excessive consumption of animal protein, coffee, and alcohol)

- Hcy levels increase with age and with the use of some anticonvulsants (CBZ, PHE)

- hyperhomocysteinemia promotes premature atherosclerosis and thrombosis and is considered an independent risk factor for stroke

Management

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |