ADD-ONS / MEDICATION

Timing of anticoagulant therapy

Updated on 11/12/2023, published on 23/02/2022

Ischemic stroke

Anticoagulant therapy in acute stroke

- in general, immediate anticoagulant therapy is not recommended for patients with acute ischemic stroke (AHA/ASA 2019 III/A)

- heparin and low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) in the acute phase either do not reduce the risk of early stroke recurrence, or their subtle effect is counteracted by a higher incidence of bleeding ( FISS-tris) [Wong, 2007]

- this is also applies to patients with AFib (IST trial) [Saxena, 2001]

- the risk of bleeding is highest:

- during the first 10-14 days after the stroke

- in large infarct and severe deficit

- in patients with poorly compensated hypertension

- management of acute stroke patients already on anticoagulant therapy is discussed here

- acute anticoagulation may be considered in the following scenarios (although clinical trials have not shown efficacy):

- what to do:

- studies have shown no significant difference in efficacy between LMWH and heparin

- start with

- then switch to DOACs / warfarin (VKA)

Initiation of anticoagulant therapy in the subacute phase of stroke

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

LMWH bridging

- bridging anticoagulation involves the administration of a short-acting anticoagulant (usually LMWH) in the following situations:

- initiation of anticoagulant therapy

- periprocedural bridging → see separate chapter

Intracerebral hemorrhage

- general risk of ICH recurrence is ~2-4%/year (without anticoagulation)

- risk of ICH recurrence with anticoagulation therapy is increased and depends on the cause of bleeding and the type of drug used ( DOAC vs. low-dose DOAC vs. warfarin)

- ↑ risk in patients with proven cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) on GRE (if amyloid angiopathy is suspected ⇒ the risk of ICH is increased 7-fold)

- ↑ risk in lobar hematomas (> 4%/year)

- ↑ risk in patients with apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4)

- ↑ risk in patients with proven cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) on GRE (if amyloid angiopathy is suspected ⇒ the risk of ICH is increased 7-fold)

- according to meta-analyses (mainly from warfarin trials), reintroducing anticoagulation therapy reduces the risk of ischemic stroke without significantly increasing the risk of ICH (Sembill, 2019) [Murthy, 2017]

- the RETRACE trial (meta-analysis) indicates that the resumption of anticoagulation therapy improves outcome regardless of the type of hematoma

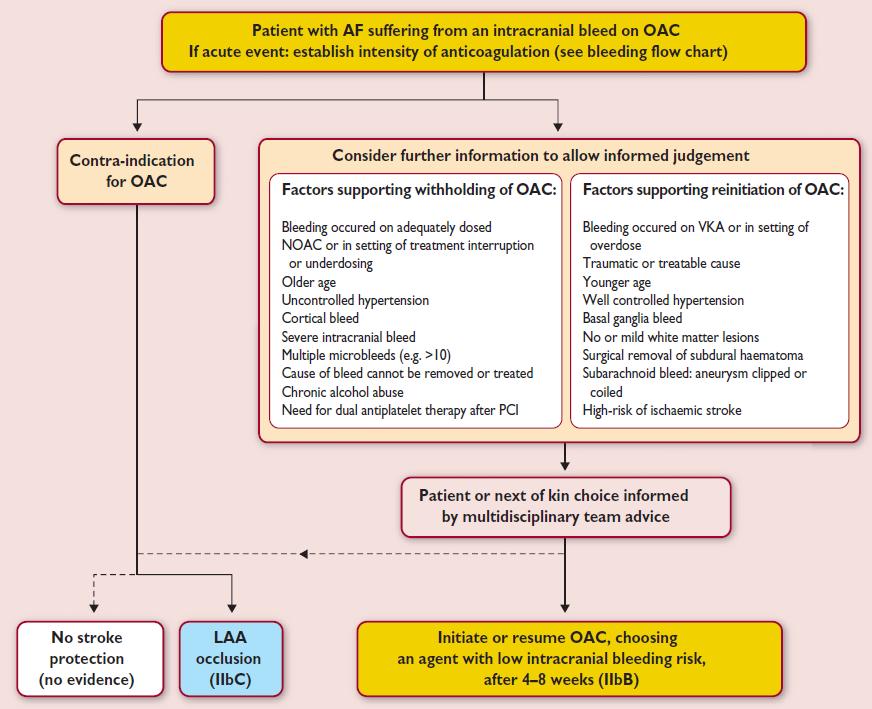

- clinical decision-making regarding the use of antithrombotic medications after ICH remains challenging

- when determining the indication/timing of anticoagulation after ICH, the risk of thromboembolism and bleeding should be assessed in the context of multiple factors

- in patients with Afib who suffered an ICH while on anticoagulant therapy, resuming anticoagulation was associated with a lower risk of stroke and a similar risk of recurrent ICH compared to the control group [Murthy, 2017]

- no other randomized trials are available; only case series data are available

- the 30-day risk of ischemic stroke is ~2-3% (including patients with Afib and mechanical valve)

- if bleeding has stabilized (according to CT), heparinization with a prophylactic dose (e.g., CLEXANE 0.4 mL SC once daily) for VTE prophylaxis can be initiated within 3-4 days

- the timing of anticoagulation restart should be decided on a case-by-case basis after individual risk assessments of thromboembolism, recurrent ICH, and late ICH expansion

- in cases of subcortical hematomas with well-compensated hypertension, full anticoagulation can be started within 10-14 days

- in Afib patients, EUSI recommends an interval of 10-14 days; AHA/ASA 2022 guidelines do not specify the type of ICH and suggest 7-8 weeks (AHA/ASA 2022 2b/C-LD)

- for patients with spontaneous ICH and high-risk thromboembolic condition (e.g., a mechanical valve or LVAD), early resumption of anticoagulation is reasonable

- > 14 days after the index event seems appropriate for patients with a mechanical valve [Kuramatsu, 2018]

- prefer DOAC; if VKA is used, careful dose titration is essential (as INR fluctuations increase the ICH risk)

- in Afib patients, EUSI recommends an interval of 10-14 days; AHA/ASA 2022 guidelines do not specify the type of ICH and suggest 7-8 weeks (AHA/ASA 2022 2b/C-LD)

- in cases of lobar hematoma, the high risk of bleeding recurrence with anticoagulation therapy (>4%/year) may neutralize the benefit in preventing thromboembolism ⇒ consider DOAC at a reduced dose (antiplatelet therapy is ineffective and also increases bleeding risk)

- restart anticoagulation in 7-8 weeks (AHA/ASA 2022 2b/C-LD)

- according to the RETRACE trial, there is a benefit of continued AC therapy even in lobar hematomas

- ESC guidelines 2016 specifically recommend using anticoagulants with a low risk of IC bleeding (DOACs)

- LAA occlusion may be considered to reduce the risk of thromboembolic events in patients with Afib and spontaneous ICH who are considered ineligible for anticoagulation (AHA/ASA 2022 2b/C-LD)

| Factor | for | against |

| Etiology of bleeding | ||

|

hypertensive bleeding, proper blood pressure control is essential

|

||

|

amyloid angiopathy, particularly associated with large lobar hematoma

|

||

| high HAS-BLED score | ||

| bleeding occurred while taking a VKA (or due to a VKA overdose) | ||

| bleeding occurred while taking the correct dose of DOAC | ||

| traumatic bleeding | ||

| alcohol/drug abuse |

||

| another cause of bleeding that cannot be eliminated | ||

| SAH with secured aneurysm (embolization/clipping) |

||

| Microvascular risks | ||

| cerebral microbleeds | ||

| no or mild leukoencephalopathy (→ FAZEKAS scale) |

||

| Indication for anticoagulant therapy | ||

| secondary stroke prevention | ||

| primary stroke prevention | ||

| Afib with a high CHA2DS2Vasc score |

||

| Afib with a low CHA2DS2Vasc score |

||

| mechanical valve |

||

| hypercoagulable state |

||

| assumption of complicated INR controls (VKA) | ||