ADDONS / GENERAL NEUROLOGY

Differential diagnosis of visual impairment

Updated on 12/10/2024, published on 26/02/2024

- the diagnosis of visual impairment is based on the patient’s medical history, clinical examination (neurologic and ophthalmologic), and laboratory and imaging studies

- the nature and dynamics of the visual disturbance, together with associated symptoms, are essential for the topical-etiological diagnosis

- vascular lesions typically involve the retina and optic nerve (ICA territory), optic radiation, and visual cortex (MCA, PCA)

- negative symptoms

- decreased visual acuity, blurry vision

- impaired color/contrast perception

- visual field defects

- night blindness – difficulty seeing in dim light

- positive symptoms

- phosphenes = simple visual sensations, such as flickering or spots of light (usually benign)

- photopsia = more complex visual phenomena, such as prolonged flashes or shimmering lights

- visual hallucinations = individuals see things that are not present in the external environment

Visual impairment can be caused by disabilities outside the visual pathway, such as refractive error, optic media opacity, or retinal lesions. In refractive errors, in addition to the difference between distance and near vision, evidence of opacities also indicates a normal pupillary response to light, as opposed to an impairment of the visual pathway

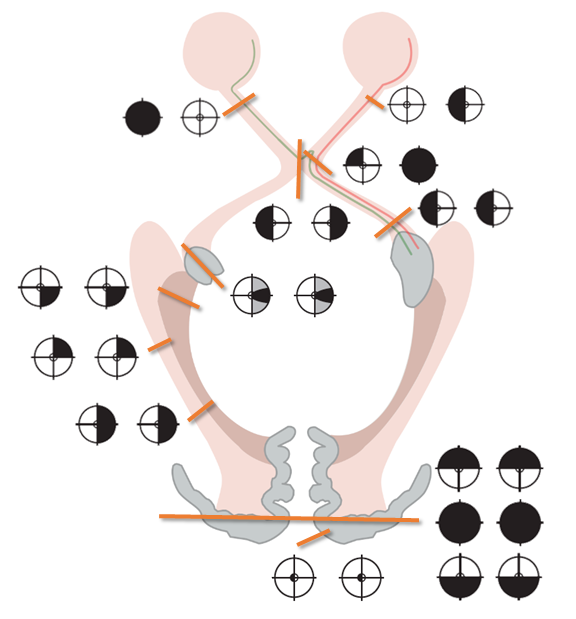

- unilateral (monocular) disorder is typically caused by a lesion in the retina or optic nerve (prechiasmatic lesion)

- except for rare cases where a CGL lesion may cause monocular impairment [Liu, 2019]

- binocular defect may occur due to:

- lesions of the chiasm and postchiasmatic lesions

- bilateral optic nerve/retina lesions

- lesions that are distal to the chiasm cause hemianopia

- fogging that lasts several seconds is a common symptom of papilledema

- sudden onset is typical for vascular (arterial and venous) disorders

- sudden unilateral loss of vision lasting several minutes ⇒ usually amaurosis fugax due to arterial ischemia

- transient visual disturbance (~ 20-30 min) beginning with central scotoma and scintillating scotomas ⇒ ophthalmic migraine

- rapid progression (within hours to days) is common in acute neuritis or acute external optic nerve/chiasm compression

- transient worsening after physical exertion or overheating (fever, hot bath) occurs in multiple sclerosis and is known as Uhthoff’s phenomenon

- slow development of the disorder (over weeks to months) usually occurs due to compression of the visual pathway by benign tumors (such as meningioma, pituitary adenoma)

- fluctuations may occur with cystic tumors (craniopharyngioma) or saccular aneurysms and papilledema

- retrobulbar pain with eye movement suggests optic neuritis (along with the typical central scotoma or decreased sensitivity throughout the visual field of the affected eye)

- hemicrania and painful palpation of the temporal artery preceding monocular visual loss are suspicious for temporal arteritis

- associated oculomotor disturbances localize the lesion to the orbital apex or parasellar area

- simple visual hallucinations (flashes) suggest irritation of the visual cortex; complex forms (objects, landscapes, persons, events) are associated with lesions in the temporal lobe

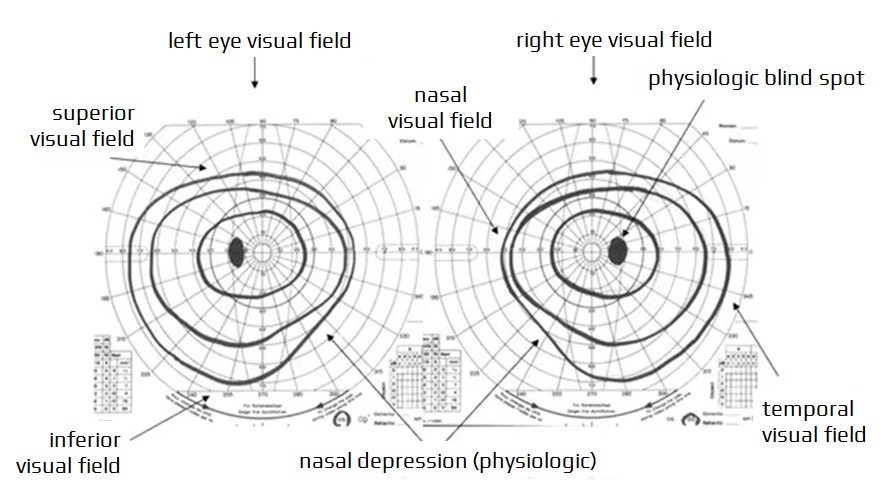

- a focal visual field defect is called a scotoma

- caused by ocular or neurological disorders, its characteristics may help in topical-etiological diagnosis

- classification of scotomas

- absolute x relative (absolute scotoma encompasses all qualities of vision)

- positive (patient is aware of the defect) x negative (patient does not perceive the defect)

- physiological scotoma – a blind spot corresponding to the optic nerve head; this scotoma is not perceived as it is compensated by the fellow eye

- sectoranopia – a wedge-shaped loss of visual field (e.g., in lesions of the optic chiasm or LGN) (Pasu, 2015)

- quadrantanopia – loss of vision in one quadrant of the visual field

- bitemporal upper quadrantopia – bilateral loss of one quadrant of the visual field, indicating compression of the chiasm from below (e.g., pituitary adenoma).

- bitemporal lower quadrantanopia – is a consequence of compression of the chiasm from above (e.g., craniopharyngioma, internal hydrocephalus)

- hemianopia – loss of vision in half of the visual field

- heteronymous hemianopia

- binasal – loss of both nasal halves of the visual field

- tumor or aneurysm compressing both optic nerves or chiasm

- glaucoma or retinal diseases affecting both their temporal halves (e.g., retinitis pigmentosa)

- bitemporal – chiasmatic lesion (e.g., pituitary adenoma, meningioma, craniopharyngioma, aneurysm, glioma)

- binasal – loss of both nasal halves of the visual field

- homonymous quadrantanopia – affects the same halves (i.e., nasal or temporal) of the visual fields on both eyes

- lesions of the optic tract, lateral geniculate body, optic radiation

- altitudinal hemianopia affecting both upper or lower halves of the visual field (bilateral cortical lesions, usually of ischemic origin)

- in hemianopia incongruent lesions (different shape/range in the visual fields of both eyes) and congruent lesions (bilateral identical defects) are distinguished

- heteronymous hemianopia

- cortical (preserved pupillary light reflex) or total blindness

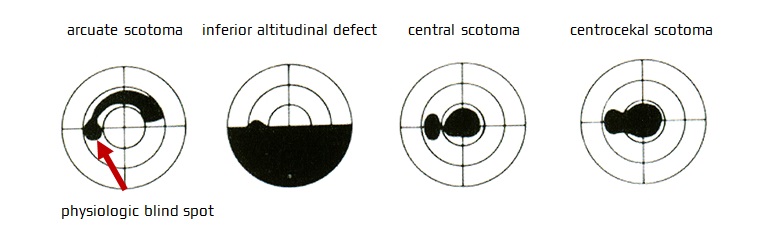

Scotoma classification according to localization and shape

- central scotoma – indicates a lesion of the maculopapular bundle

- typically seen in optic neuritis, often accompanied by retrobulbar pain

- rapid compression of the optic nerve leading to the loss of maculopapular fibers (slow compression initially leads to peripheral defects)

- macular diseases (e.g., macular degeneration)

- ischemic optic neuropathy (though it more commonly causes altitudinal visual field defects)

- optic atrophy (e.g., caused by tumor compressing the nerve, toxic/metabolic damage)

- rarely, lesions of the occipital lobe

- centrocecal scotoma – involves the center + blind spot

- toxic optic neuropathy

- Leber’s optic atrophy

- arcuate (Bjerrum) scotoma (deficiency of nerve fiber bundles) – originates from the blind spot and encircles the center from above or below

- e.g., glaucoma, chorioretinitis

- less commonly, ischemic optic neuropathy (especially non-arteritic)

- drusen of the optic disc and high myopia

- monocular altitudinal lower or upper visual field loss

- Ischemic optic neuropathy (ION)

- may also be caused by occlusion of the ciliary artery (CRA)

- less commonly, in glaucoma

- optic chiasmatic junction scotoma (Traquair’s junctional scotoma) – on the side of compression, there is a central scotoma, on the other side, there are peripheral depressions in the temporal upper quadrant from a lesion at the junction of the optic nerve to the chiasm (e.g., perisellar meningiomas)

- anular scotoma – in the mid-periphery, it is a stage in the development of tapetoretinal degeneration

- concentric narrowing (tunnel vision) is rarely due to optic perineuritis

- advanced glaucoma, retinitis pigmentosa

- chronic stasis papilla

- occlusion of the central retinal artery with preservation of the cilioretinal artery

- bilateral infarction of the occipital lobes with preservation of the areas corresponding to the maculae

- functional vision disorders

- quinine poisoning and others

Retinal lesions

- retinal lesions are usually painless, with abnormal fundoscopic findings in the acute stage

- involvement of the inner layer of the retina (e.g., in the CRA occlusion) leads to monocular visual field defects

- degenerative retinal lesions (e.g., retinitis pigmentosa) or glaucoma are characterized by concentric narrowing of the visual field or annular scotomas

- retinal detachment occurs when the retina separates from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choroid

- it can cause sudden vision loss or a curtain-like shadow in the visual field, often preceded by flashes of light (photopsia)

- occlusion of retinal blood vessels can lead to ischemia and subsequent vision loss

- transient monocular vision loss (amaurosis fugax) → more here

- permanent vision loss → more here

- etiology – embolism (thrombi, cholesterol, plaque fragments), vasospasm, etc.

- fundoscopic examination shows

- normal or pale disc

- retinal pallor and edema

- cherry-red spot (macular area, which is supplied by the choroidal circulation, appears relatively red compared to the surrounding pale ischemic retina)

- attenuated arterioles

- cotton wool spots

- emboli (cholesterol or calcific) may be visible within the retinal arterioles as bright, refractile lesions (Hollenhorst plaques)

- unilateral vision loss is a typical clinical presentation, often caused by macular edema (with or without concurrent macular ischemia).

- branch RVO may present with peripheral visual field defects or may be asymptomatic

- the speed of vision loss varies depending on the extent and location of the occlusion and the presence of associated complications, commonly over a period of hours

- fundoscopy shows extensive retinal hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, macular edema, and tortuous dilated retinal veins

- progressive retinal damage due to increased intraocular pressure

- asymptomatic in the early stages, with the gradual appearance of scotomas

- diagnosis is made by measuring intraocular pressure

- regular preventive measurements are recommended from around the age of 40

Optic nerve lesions

- a condition where the blood supply to the optic nerve is compromised

- sudden, painless loss of vision in one eye with reduced visual acuity, altitudinal visual field defect is common → Ischemic optic neuropathy

- diagnosis is often based on clinical examination findings (characteristic optic disc swelling or atrophy) and imaging studies such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) or visual field testing (CT perimeter)

- neuritis is the most common optic nerve lesion, typically caused by an autoimmune process (such as MS)

- a maculopapular bundle lesion with central/centrocecal scotoma is typical

- optic disc may appear normal, edematous, or atrophic during the fundoscopic examination, depending on the temporal profile and location of the lesion

- edema is present in inflammation affecting the intraocular segment of the nerve (papillitis) but not in retrobulbar lesions (retrobulbar neuritis)

- atrophy develops > 4 weeks after onset due to degeneration of retinal ganglion cell axons

- Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is a rare inherited disease caused by a mutation in the mitochondrial genome (maternally inherited)

- it typically affects young adults (onset in the 2nd-3rd decade), with a male predominance (4:1)

- characterized by loss of central vision; impairment is bilateral, initially asymmetric

- in the acute stage, the fundus resembles edema in papillitis (pseudoedema) but without leakage on fluorescein angiography

- in the chronic stage, differentiation from other causes of optic atrophy is difficult

- causes of compression

- ophthalmic and carotid artery aneurysms

- tumors in the sellar region (pituitary adenoma, craniopharyngioma, meningioma)

- glioma of the optic nerve

- meningeal infiltration (carcinoma, leukemia, and lymphoma or sarcoidosis)

- intracranial hypertension → papilledema

- chronic papilledema leads to concentric narrowing of the visual field and enlargement of the blind spot

- “benign” intracranial hypertension leads to papilledema and initially to enlargement of the blind spot, mild concentric narrowing, and loss of vision in the lower nasal quadrants

- in later stages, it may lead to permanent vision loss

- trauma can cause varying degrees of vision loss

- nutritional (B1, B12 deficiency)

- toxic (ethambutol, methanol, isoniazid)

- infectious (syphilis, Lyme disease)

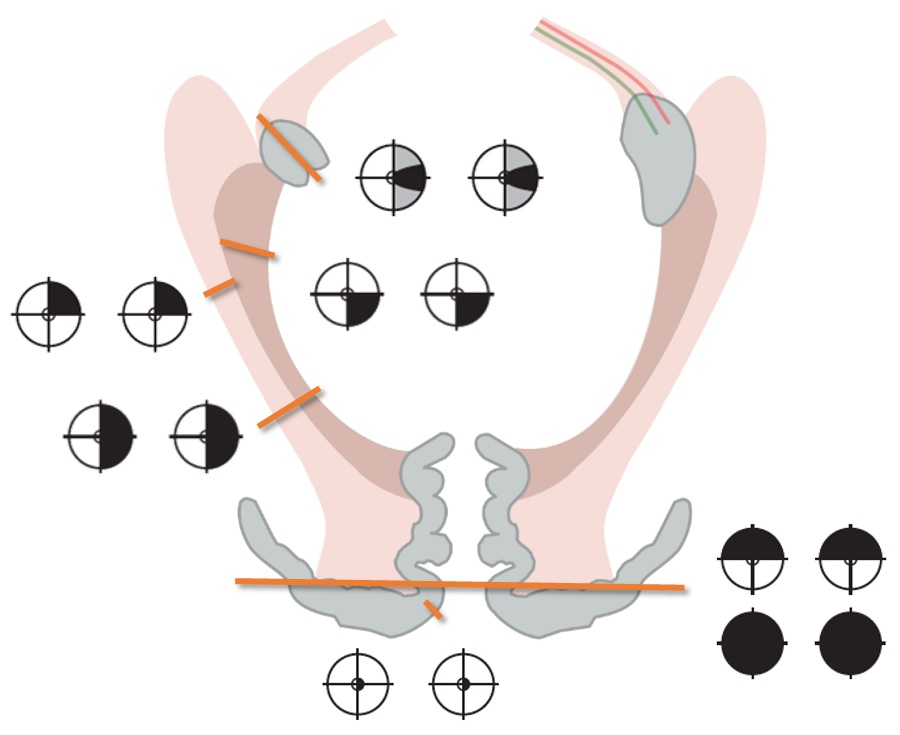

Optic chiasm lesions

- the clinical presentation depends on the location and etiology of the lesion

- bitemporal hemianopsia is the most common manifestation

- patients with slowly developing lesions often have no subjective visual complaints; some present with double vision due to non-corresponding nasal halves of the visual fields

- compression of the chiasm from below leads to a predominance of impairment in the upper parts of the temporal hemifields (superior bitemporal quadrantanopia)

- superior compression typically manifests as inferior bitemporal quadrantanopia

- junctional scotoma – lesion of the anterior part of the chiasm

- lesion of the nasal fibers before they cross leads to an ipsilateral temporal defect (junctional scotoma of Traquair)

- lesion of the anterior part of the chiasm leads to an ipsilateral centrocecal scotoma and a defect in the contralateral superior temporal quadrant (from the involvement of Willebrand’s knee of crossing fibers from the contralateral nasal retina

- binasal hemianopia

- external bilateral compression of the chiasm due to bilateral aneurysm of the internal carotid artery, hydrocephalus, or skull base tumor

- eye diseases (glaucoma, optic nerve drusen, congenital hypoplasia of the optic nerve, sectoral retinitis pigmentosa)

- external bilateral compression of the chiasm due to bilateral aneurysm of the internal carotid artery, hydrocephalus, or skull base tumor

- optic tract is also affected in cases of large sellar expansion, a prefixed chiasma, or a dorsally propagating expansion

- prefixed chiasm = if the optic nerves are short and the gland lies below the posterior part of the chiasm

- suprasellar lesions leading to compression of the chiasm may result in lesions of CN III, IV, VI, and the first and second branches of CN V

Optic tract and lateral geniculate body lesions

- complete lesions of the optic tract and lateral geniculate body (nucleus) lead to contralateral homonymous hemianopia

- partial lesions lead to partial homonymous hemianopia (defects are often not congruent)

- additionally, there is a contralateral relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) and temporal ipsilateral pallor of the optic disc

- etiology:

- expansive sellar and parasellar processes (especially craniopharyngioma and aneurysm)

- demyelination

- ischemia

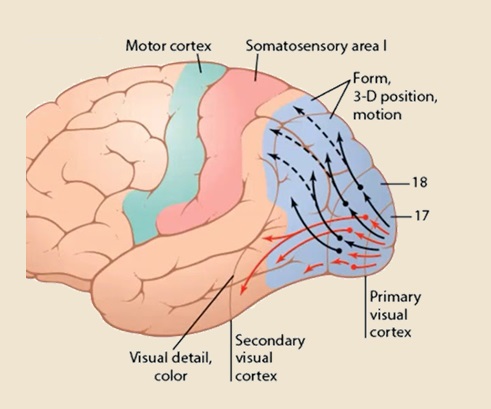

Optic radiation lesions

- lesions of the optic radiation in the temporal lobe lead to contralateral superior homonymous quadrantanopia

- lesions of the radiation in the parietal lobe lead to contralateral inferior homonymous quadrantanopia

- a complete lesion of the optic radiation results in contralateral homonymous hemianopia

- pupillary responses are preserved in these cases

- additional associated hemispheric symptoms accompany hemianopia caused by lesions of the optic radiation:

- lesions of the temporal lobe lead to memory impairment, Wernicke aphasia

- lesions of the dominant parietal lobe manifest as conduction aphasia, Gerstmann syndrome (finger agnosia, agraphia, acalculia, left-right disorientation), or tactile agnosia

- lesions of the non-dominant parietal lobe manifest as left-sided neglect syndrome, constructional apraxia, or dressing apraxia

- visual disturbances from lesions of the parieto-occipital junction or occipital lobe – Balint syndrome and cortical blindness

- deep parietal lesions can lead to homonymous hemianopsia and altered pursuit eye movements toward the homolateral side

Occipital lobe lesions

- unilateral lesions of the occipital lobe lead to contralateral homonymous congruent hemianopia with typical central (macular) sparing

- the explanation for preserved central vision is twofold

- vascular supply of the occipital pole

- bilateral cortical representation of the macula

- hemianopia caused by infarction of the occipital lobe due to vertebrobasilar thrombosis may be accompanied by brainstem and cerebellar symptoms

- the explanation for preserved central vision is twofold

- lesions limited to the area above or below the calcarine fissure lead to quadrantanopia

- bilateral lesions of the visual cortex above or below the calcarine fissure lead to altitudinal hemianopia

- cortical blindness results from bilateral lesions of the occipital lobe

- absent reaction to a rapidly approaching object (blinking) and absence of optokinetic nystagmus

- unlike blindness caused by lesions anterior to the LGN, the pupillary light reflex is preserved

- some patients may confabulate visual perception or deny their blindness (Anton’s syndrome)

- Anton’s syndrome is a rare condition named after the Austrian psychiatrist Gabriel Anton

- it is characterized by individuals with cortical blindness, typically resulting from bilateral occipital lesions, who deny their blindness

- despite being unable to see, patients with Anton’s syndrome may adamantly insist that they can see normally

- this phenomenon is often accompanied by confabulation, where patients fabricate explanations or scenarios to explain their visual experiences despite lacking true visual perception

- patients may resist efforts to provide appropriate care or rehabilitation

- this syndrome illustrates the complex interplay between perception, awareness, and higher cognitive functions

Visual association cortex lesions

- lesions of the ventromedial occipital lobe m\ay cause abnormal color perception in the contralateral hemifields (hemiachromatopsia) [Short, 2001]

- in lesions in the dominant hemisphere involving the splenium of the corpus callosum or adjacent periventricular white matter, pure alexia occurs as part of a disconnection syndrome (right-sided homonymous visual field defect and inability to evoke lexical visual information that is processed in the intact right occipital lobe)

- visual agnosia is associated with bilateral damage to the medial occipitotemporal region, involving the inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF), which connects the primary visual cortex to the visual associative areas of the temporal lobe

- prosopagnosia (face recognition disorder) – may result from various lesions → see here

- motion perception disorder – observed in lesions of Brodmann area 39 or the lateral occipitotemporal cortex

- neglect syndrome – typically caused by a lesion of the non-dominant hemisphere

- extensive lesions lead to both neglect syndrome and hemianopia; neglect syndrome may be difficult to demonstrate in such cases unless tactile or motor neglect is also present

- Balint syndrome – described in bilateral parietal lesions

- visual ataxia + simultanagnosia + ocular apraxia

- neglect syndrome, also known as hemispatial neglect or unilateral neglect, is characterized by a failure to attend to or be aware of stimuli presented on one side of space, typically opposite to the side of the brain injury

- typically caused by lesions in the right hemisphere, resulting in neglect of the left side of space

- exact locations differ based on the modality affected

- it may affect both motor and sensory modalities (visual, auditory, and tactile neglect)

- visual neglect is the most common, characterized by a lack of awareness of visual stimuli presented in the neglected visual field (a patient may only draw or describe objects on the right side of a scene, ignoring those on the left)

- individuals may neglect motor actions related to the affected side (they may fail to eat food from the left side of a plate or neglect to groom the left side of their body)

- anosognosia = a lack of awareness or insight into one’s neurological disorder (e.g., patients neglect their hemiparesis)

- neglect syndrome can significantly impact daily functioning and rehabilitation efforts (specific techniques are required to manage this condition effectively)

- a rare disorder characterized by a triad of symptoms involving visuospatial dysfunction, first described by the Hungarian neurologist Rezső Bálint in 1909

- typically associated with bilateral lesions in the parietal and occipital lobes, particularly in the posterior parietal cortex and the superior occipital gyrus

- symptoms of Balint syndrome:

- simultanagnosia

- difficulty perceiving the visual field as a whole

- patients may only be able to focus on one object at a time and struggle to perceive multiple objects simultaneously; this results in a fragmented perception of their surroundings

- optic ataxia

- patients with optic ataxia have difficulty accurately reaching for objects in their visual field, even though their vision and motor function are otherwise intact

- they may misreach or fumble when attempting to interact with objects

- ocular apraxia

- patients have difficulty voluntarily directing their gaze toward specific objects or locations despite having intact visual acuity

- they may exhibit difficulty shifting their gaze between objects or initiating saccadic eye movements

- simultanagnosia

- hemineglect, which usually results from lesions in the temporoparietal junction, should be distinguished from Bálint syndrome