ISCHEMIC STROKE

Vertebrobasilar stroke

Updated on 11/06/2024, published on 20/06/2023

- posterior circulation strokes account for 20-25% (range 17-40%) of ischemic strokes

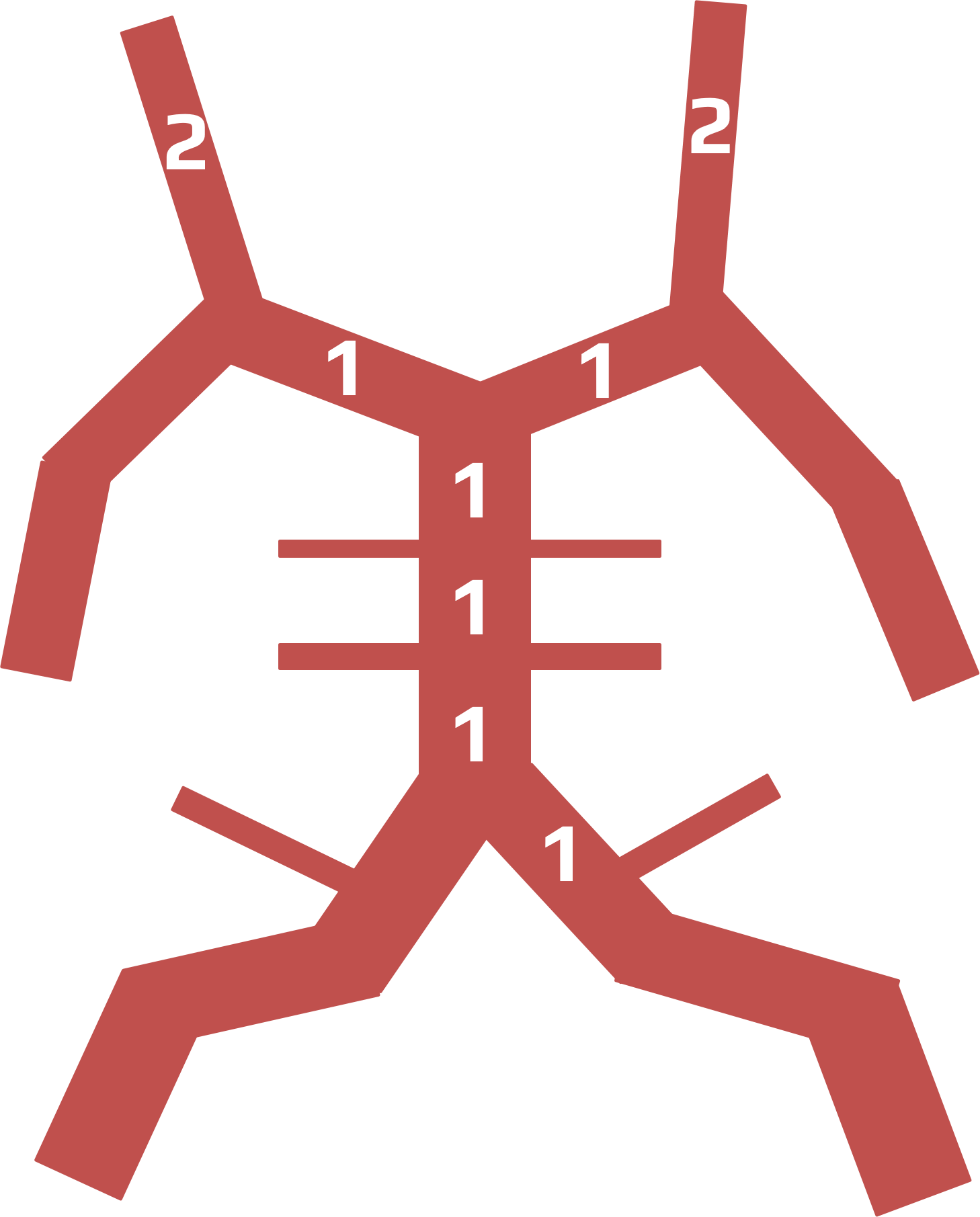

- posterior (vertebrobasilar) circulation includes the vertebral (extra- and intracranial), basilar, and posterior cerebral arteries, as well as their branches

- it supplies the posterior regions of the brain (brainstem, thalamus, cerebellum, and the occipital and temporal lobes)

- in general, the term vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) describes inadequate blood flow through the posterior circulation

- it can be either transient (transient ischemic attack (TIA), drop attack, Bow Hunter’s syndrome) or permanent (infarct)

- several mechanisms leading to hypoperfusion may be involved and even combined (embolism, atherothrombosis, external mechanical compression, steal syndrome)

- the term has been overused (often referring to various nonvascular vertiginous conditions in the geriatric population), and its use is currently discouraged

- certain occlusions cause characteristic clinical patterns and syndromes

- however, vertebrobasilar stroke shares features with other conditions (stroke mimics); differential diagnosis in the acute setting can be challenging

- DDx of vertigo (labyrinthitis, vestibular neuritis, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, etc.)

- DDx of impaired consciousness (metabolic coma, nonconvulsive seizure, etc.)

- the outcome depends on the location and extent of the stenosis/occlusion, the quality of the collateral circulation, and adequate and timely therapy

- if extensive basilar artery occlusion (BAO) is left untreated, the mortality rate is over 90%

- strokes in the posterior territory have a higher risk of recurrence compared to those in the carotid territory (Werring, 2014)

- the risk of recurrence after a previous stroke/TIA with VA/BA stenosis ≥ 50% is ~ 22% within 90 days (Gulli, 2013) [Marquardt, 2009]

Clinical presentation

- the symptoms of a vertebrobasilar stroke can differ significantly among patients, depending on the type of occluded artery, the extent of occlusion, and the quality of the collateral circulation

- a combination of symptoms is common → see Topical diagnosis of stroke

- while traditional brainstem syndromes have been described, some symptoms may not be specific (DDx of vertigo)

- vestibular syndrome (vertigo, nystagmus, tonic deviations)

- isolated vertigo is usually of nonvascular origin

- nonspecific balance disorders must be distinguished (see below)

- vertigo due to stroke is usually associated with other brainstem and cerebellar symptoms.

- nausea and vomiting

- eye movement disorder (nuclear/supranuclear) +/- diplopia

- visual field disturbances

- signs of sympathetic lesions

- ataxia and/or dysmetria

- dysarthria/dysphonia

- dysphagia

- paresthesia/hypesthesia in the face and/or extremities and trunk

- combination of paresis or sensory deficit in the extremities

- hemiparesis or quadriparesis

- isolated hearing loss is typically not caused by stroke (except for occlusion of the labyrinthine artery)

- alternating syndromes are typical for localized brainstem lesions with an ipsilateral nuclear lesion of a cranial nerve, Horner’s syndrome or cerebellar syndrome, and contralateral fascicular disorder (hemiparesis or hemihypesthesia)

- larger occlusions lead to impaired consciousness (coma may be the initial manifestation) → Examination of the patient with impaired consciousness

- transient circulatory disturbances may also cause drop attacks

Etiopathogenesis

Identifying the underlying mechanism and risk factors is crucial for stroke prevention as it affects the choice of optimum preventive measures

- the most frequent causes of vertebrobasilar stroke are atherosclerosis (AS) and arteriolopathy; cardioembolism is less common

- AS lesions are most commonly located in the V0 and V4 segments of the vertebral arteries, in the proximal and middle segments of the basilar artery, and in the P1 segment of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA)

- occlusion of a perforator results in lacunar stroke

- AS lesions are most commonly located in the V0 and V4 segments of the vertebral arteries, in the proximal and middle segments of the basilar artery, and in the P1 segment of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA)

- arterial dissection most commonly affects the V3 segment

- typical presentations include neck or occipital pain +/- TIA or infarction

- stenosis can cause:

- atherothrombotic occlusion

- perforator occlusion

- thromboembolism

- hypoperfusion in distal segments

- steal phenomenon

- occurs with stenosis/occlusion of the proximal segments of the subclavian artery or brachiocephalic trunk

- usually causes only transient symptoms (dizziness), not stroke

- Bow-Hunter’s syndrome (also known as rotational vertebral artery syndrome) – transient ischemic symptoms caused by external mechanical compression of the vertebral artery (usually at the C1-2 level) during lateral flexion or rotation of the head, often in combination with contralateral stenosis

- a less common cause of stroke is dolichoectasia and its complications

- flow stasis increases the likelihood of thrombus formation

- arterial wall stress predisposes to dissection

- enlarged artery may cause a mass effect on adjacent neural structures

Diagnostic evaluation

- diagnosis is based on a careful history with a detailed clinical examination and the correct indication and interpretation of imaging studies

- all cases of suspected stroke require urgent brain imaging to exclude haemorrhage, vessel imaging is essential to identify artery occlusion. It should be performed without delay, as minimizing the time between stroke onset and initiation of thrombolysis is associated with a good outcome

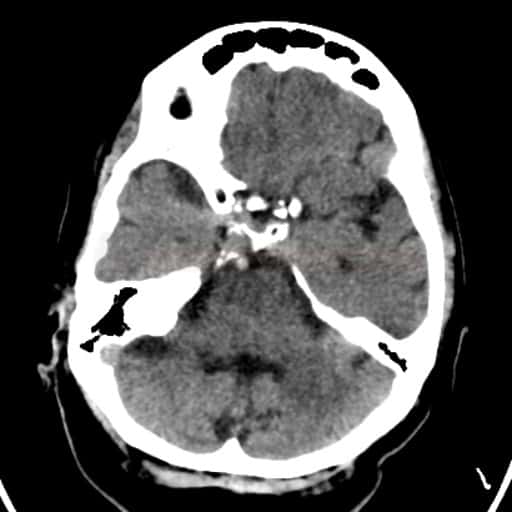

Neuroimaging

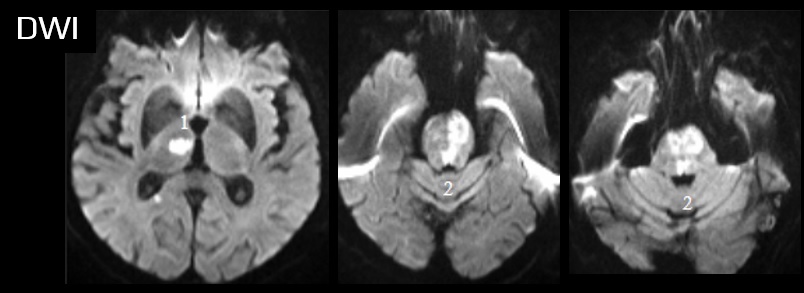

Brain imaging

- brain CT

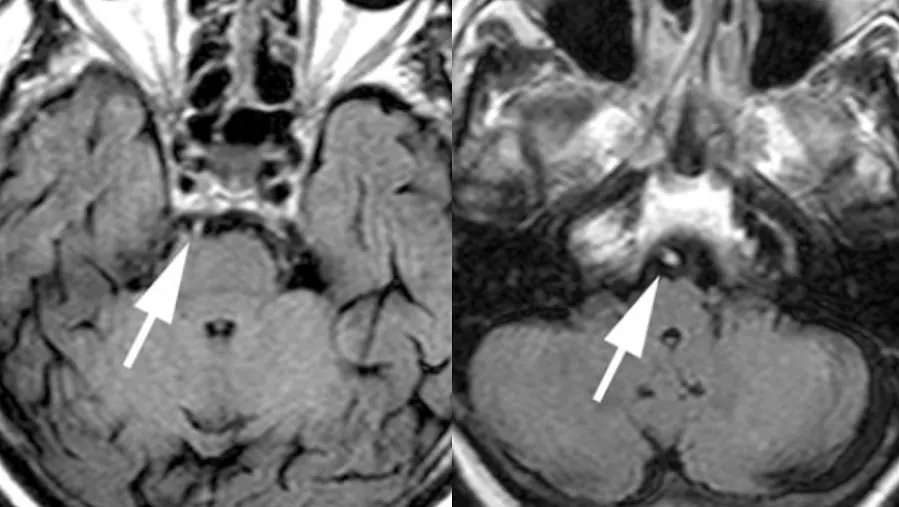

- brain MRI

- optimal imaging method for posterior circulation stroke

- higher sensitivity compared to CT; small lesions may not be visible on the initial CT

- MR DWI confirms ischemia

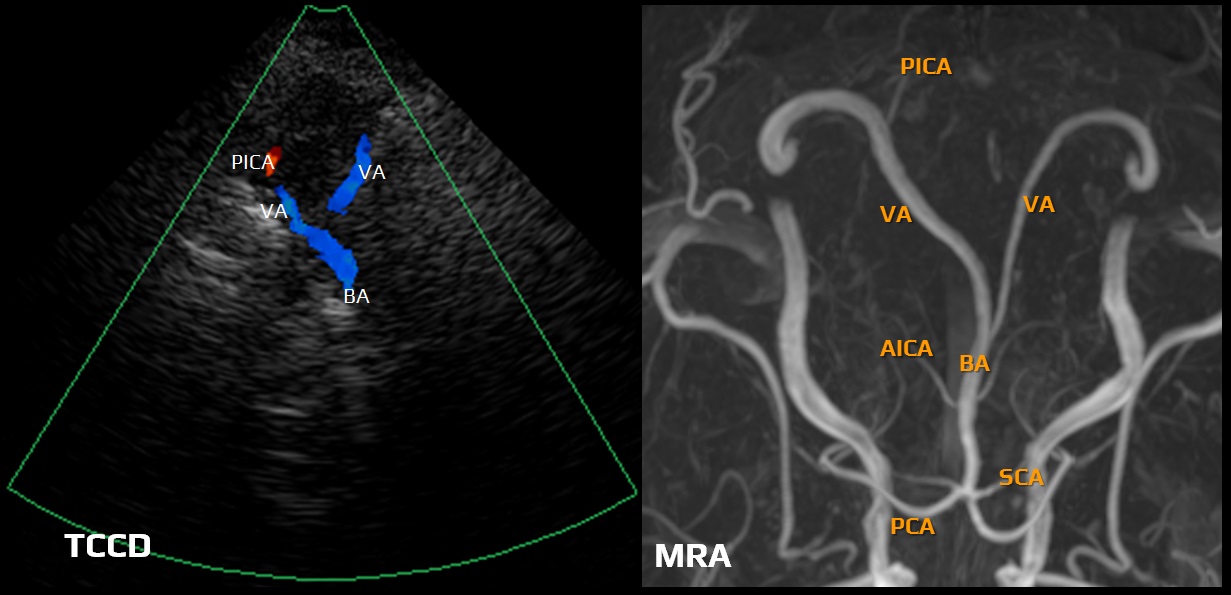

Vascular imaging

- CT angiography / MR angiography

- CTA is a fast and widely available method with high sensitivity (~ 94%)

- the accuracy of MRI in the distal posterior circulation is comparable to CTA, but imaging of the aortic arch and the origin of the vertebral arteries is problematic

- in the acute stage, exclude occlusion of the V4 segment, vertebral junction, BA, and/or PCA, which could be solved by recanalization therapy

- it secondary prevention, it is essential to manage potential stenoses properly (mainly in the prevertebral segments of the subclavian artery, the origin of VA, and in the V4 segment and BA)

- neurosonology

- allows to assess hemodynamics, steal phenomenon

- enables repeated monitoring

- carefully examine the V0 segment

- dynamic tests (during rotation, ante-and retroflexion) can exclude external VA compression (Bow Hunter’s syndrome)

- exclude steal phenomenon

- with difficult BA insonation, its patency can be verified by tapping the VA retromastoidally while detecting the undulations in the PCA

- DSA

- DSA is reserved for endovascular procedures and is rarely used as a stand-alone diagnostic tool

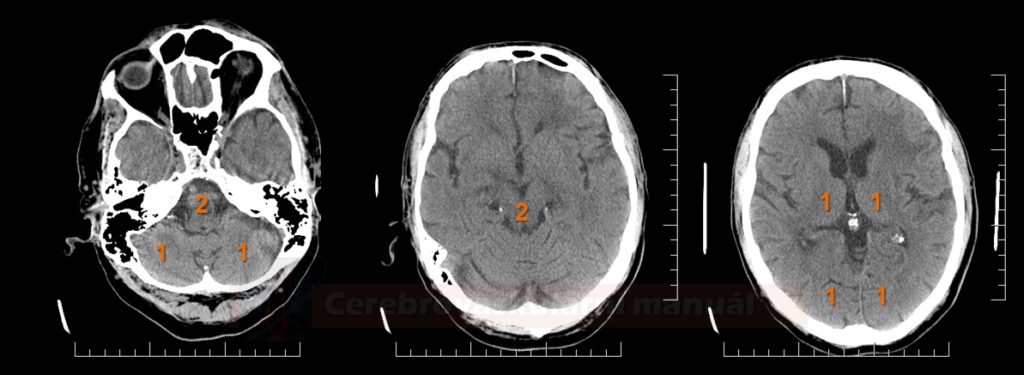

Radiological predictors of clinical outcome in basilar artery occlusion

Etiology

- the same etiologies apply to both vertebrobasilar and carotid territories → Etiologic classification of ischemic stroke

- Bow-Hunter’s syndrome and subclavian steal phenomenon are specific to the posterior circulation

Differential diagnosis

- ischemia or hemorrhage in the brain stem and cerebellum does not usually cause diagnostic difficulties due to typical symptoms

- nonvascular etiologies (external brainstem compression, brainstem tumor) must be excluded

- isolated vertigo and altered consciousness are challenging because of the wide range of potential etiologies

- not every vertigo is of vascular origin (especially in the elderly)

- dizziness should always be specified and accurately described – distinguish vestibular vertigo from various nonvestibular conditions, ataxia, or other balance disorders and psychogenic conditions

- the term vertigo should be reserved for the dizziness of vestibular origin

- distinguish other nonspecific conditions (weakness, fainting, blurred vision, or unsteady gait)

- to determine whether the dizziness is vestibular, nonvestibular, or caused by another balance disorder, the following should be obtained and evaluated:

- an accurate description of the current condition, including associated symptoms (hearing loss, lesions of other cranial nerves, brainstem, and cerebellar symptoms)

- onset (sudden x gradual), duration, and provoking factors (e.g., head or body movement or position)

- course (constant x fluctuating, spontaneous worsening x improvement)

- consider the patient´s age

- these possibilities must be distinguished based on the patient’s history:

- true vertigo (usually rotational) is caused by vestibular pathway dysfunction (central or peripheral)

- impaired balance without rotatory vertigo

- instability manifesting particularly when walking or standing; symptoms typically alleviate when sitting or in a supine position

- the absence of rotational vertigo suggests a nonvestibular etiology

- presyncope (fainting) and other nonspecific symptoms

- a feeling of impending fainting but without actual loss of consciousness, lightheadedness, or general malaise

- e.g., due to hypoglycemia, hyperventilation, anemia, side effects of medication, etc.

- exclude vascular etiology, especially in elderly patients with vascular risk factors, and look for subtle lesions on neuroimaging (perform DWI if possible)

- the labyrinthine artery arises from the AICA

- its isolated occlusion (rare) leads to sudden and marked impairment of hearing and vestibular function and may be clinically characterized by a peripheral vestibular syndrome

- hearing loss is usually permanent

- vestibular impairment is long-lasting, with some gradual improvement due to central compensation

- however, there is usually a concomitant occlusion of the AICA or BA, and thus, other brainstem/cerebellar symptoms can be observed

- labyrinthine infarction may be preceded by transient isolated episodes of vertigo

- a common cause of nonspecific balance problems in the elderly

- the maintenance of balance depends on the mutual integration of the visual, vestibular, and somatosensory systems

- balance problems (other than classic vertigo) can occur when any of these systems are affected in isolation or when several of them are affected simultaneously

- dizziness can be a side effect of many drugs

- older people are particularly susceptible

- aminoglycosides, salicylates (aspirin), and some diuretics (furosemide) may directly affect the vestibular system due to ototoxicity

- dizziness may also occur with tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers, etc.

- an inflammatory disorder (viral) affecting the vestibular nerve

- characterized by rotational vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and imbalance that develops over several hours

- occurs more frequently at younger ages and is not accompanied by hearing impairment or brainstem/cerebellar symptoms

- brief episodes of vertigo provoked by a particular position or movement → Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

- headaches + brainstem aura symptoms (dysarthria, vertigo, double vision, and ataxia)

- headache often starts on one side of the head and then gradually spreads and becomes more severe

- duration:

- typically, the aura symptoms develop gradually over minutes and can last up to 60 minutes

- aura can start 10-45 minutes before the onset of the headache

- the headache that usually follows may last for several hours (in some cases up to 72 hours)

- typically, the aura symptoms develop gradually over minutes and can last up to 60 minutes

- at least two attacks meeting the above criteria are required to establish the diagnosis (International Classification of Headache Disorders)

- cervical vertigo – not a true rotational vertigo with nystagmus, but rather a disturbance of balance, a feeling of instability with vegetative symptoms. Concurrent headache is common, and symptoms are typically provoked and worsened by head movements

- cardiac insufficiency – leads to impaired cerebral perfusion and may be manifested by dizziness (but never true rotational vertigo) or a tendency to faint. Symptoms are usually postural and improve in supine position

- presyncope with a feeling of weakness and spatial uncertainty

Management

Acute stroke therapy

- standard recanalization protocols apply for posterior circulation stroke except for basilar artery occlusion (BAO)

- intravenous thrombolysis

- in BAO, thrombolysis or thrombectomy can be performed without a strict time limit due to the poor prognosis; imaging methods with the assessment of tissue viability are helpful but not necessary (see above for prognostic scales) [Strbian, 2013]

- recanalization is achieved in 50-70% (depending on etiology and extent of occlusion)

- recanalization rate for thrombi > 30 mm is ~ 20-30% [Strbian, 2014]

- in BAO, thrombolysis or thrombectomy can be performed without a strict time limit due to the poor prognosis; imaging methods with the assessment of tissue viability are helpful but not necessary (see above for prognostic scales) [Strbian, 2013]

- mechanical recanalization

- intra-arterial thrombolysis (IAT)

- consider in patients with inappropriate anatomical conditions for thrombectomy

- possible treatment of significant peripheral embolization during endovascular procedures

| ESO/ESMINT 2024 guidelines on acute management of Basilar Artery Occlusion (BAO) |

| BAO can be treated within 24 hours without advanced imaging selection |

|

Conservative therapy

- standard acute antiplatelet therapy/anticoagulation in patients ineligible for recanalization therapy

Surgery

- early decompressive craniectomy in patients with extensive ischemia → malignant ischemia

- external ventricular drainage may be lifesaving in large-volume cerebellar infarction with a decreased level of consciousness attributable to acute hydrocephalus

Symptomatic acute stroke therapy

- adhere to the principles of general acute stroke management

- vertebrobasilar stroke is usually associated with vertigo, nausea, and vomiting

- thiethylperazine (TORECAN)

- available in oral, rectal, and intravenous forms

- acute extrapyramidal dystonia may occur with higher doses

- ondansetron (ONDANSETRON, ZOFRAN)

- diazepam (DIAZEPAM) – 2-10 mg IV for acute vertigo

- there is a higher risk of adverse events in the elderly

- thiethylperazine (TORECAN)

- for chronic conditions, use antivertiginous drugs only to treat true vertigo

- antivertiginous drugs are not indicated for the treatment of:

- nonspecific imbalance

- short-term dizziness (lasting seconds to minutes)

- persistent vestibular symptoms

- nonspecific imbalance

Secondary prevention

- best medical treatment (BMT)

- reconstructive procedures (stenting, endarterectomy, or reconstruction/transposition) should only be performed if the BMT fails

- no evidence suggests that revascularization of vertebral artery stenosis is superior to the BMT (negative VAST trial, etc.)

- no evidence suggests that revascularization of vertebral artery stenosis is superior to the BMT (negative VAST trial, etc.)

→ Vertebrobasilar steno-occlusive diasese

→ Prevention of ischemic stroke

Rehabilitation

- speeds up the vestibular compensation process

![pc-aspects_prognosis - Puetz pc-ASPECT score predicts prognosis [Puetz, 2009]](https://www.stroke-manual.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/pc-aspects_prognosis-Puetz.jpg)