ADD-ONS / MEDICATION

Anticoagulant therapy

Updated on 21/04/2024, published on 21/02/2022

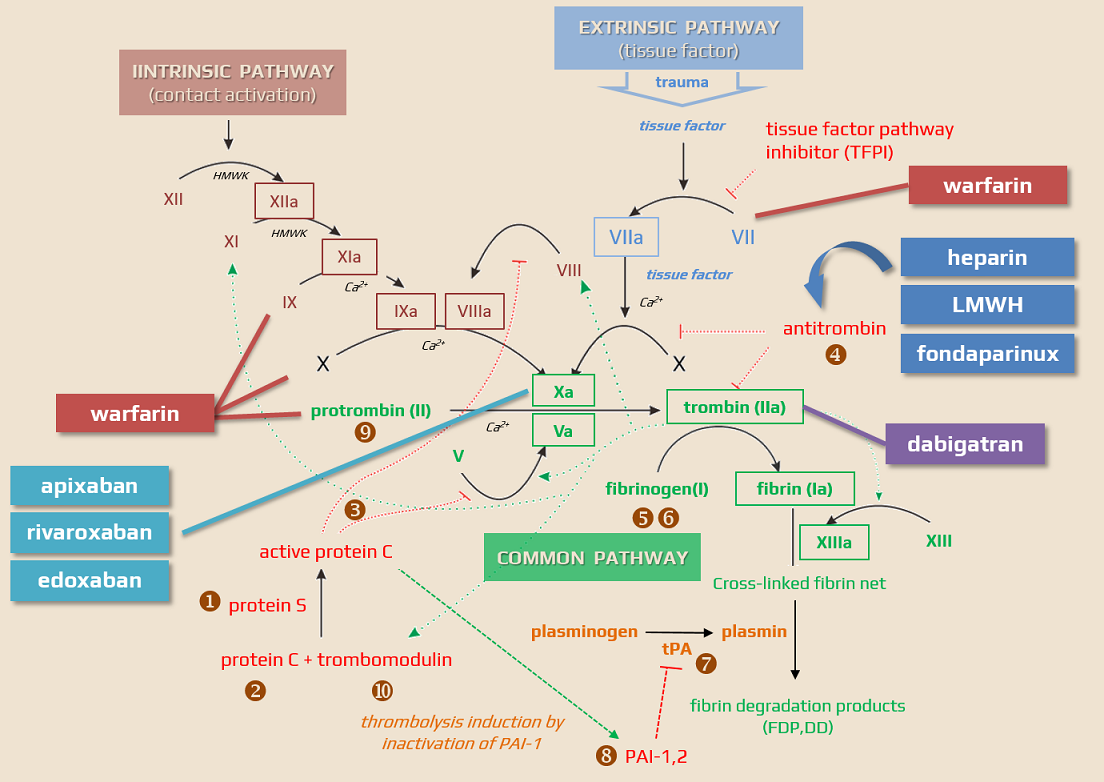

Anticoagulants are drugs that prevent the formation of blood clots by interfering with various factors in the clotting cascade. Anticoagulants are essential for the prevention and treatment of conditions associated with cardioembolism and abnormal blood clot formation. This chapter discusses their mechanisms of action, indications, monitoring, and potential complications.

Classification of anticoagulant drugs

| Direct anticoagulants They inactivate the clotting factors present in the plasma |

Indirect anticoagulants They affect clotting factors by reducing their liver production |

|

| Direct thrombin/factor Xa inhibitors These drugs bind to thrombin/factor Xa and thereby block their function |

Indirect thrombin/factor Xa inhibitors These drugs activate antithrombin |

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

Indications

- the decision to initiate anticoagulant therapy should be based on an individualized assessment of the risk of thromboembolism and bleeding

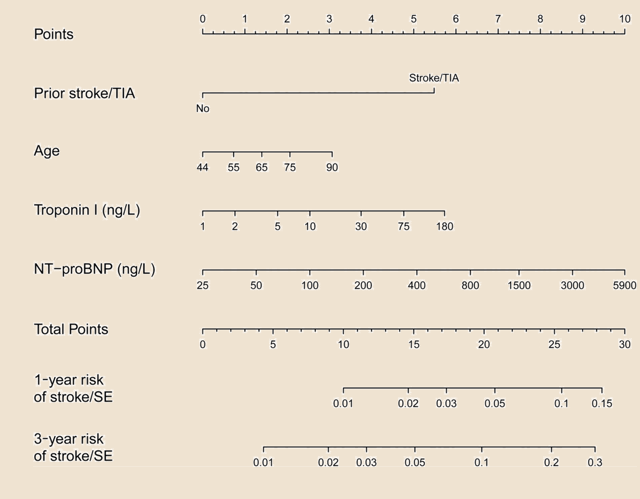

risk of ischemic stroke

CHA2DS2VASc score

spontaneous echo contrast in the left atrium

intra-atrial thrombus, etc.

- older age and hemorrhagic transformation of ischemia are not absolute contraindications to subsequent anticoagulation

- approx. risk of ICH with anticoagulation therapy:

- vitamin K antagonists (VKA) – 0.3-0.6% /year

- direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) – 0.1-0.2% /year

- concerning risk/benefit, the increased risk of falls in elderly patients is not a contraindication to anticoagulation (AAN guidelines 2014)

- in patients with CHADS2 ≥2, warfarin is safer than ASA or no therapy, even with an increased risk of falls

- elderly patients with a risk of stroke >2%/year would need to fall more than 300 times/year for warfarin not to be considered optimal therapy [Garwood, 2008]

- direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are currently preferred to warfarin (if possible)

- aspirin is not an adequate alternative to anticoagulants

- apixaban is preferred in patients at increased risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding

- aspirin is not an adequate alternative to anticoagulants

- 20-30% of ischemic strokes are caused by cardiac embolism → more about cardioembolic strokes here

- emboli are most commonly associated with:

- atrial fibrillation (50%)

- non-rheumatic and rheumatic valvular defects

- coronary artery disease (CAD)

- anticoagulation is indicated in patients with a proven cardioembolic etiology

| Selected indications and contraindications for anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and associated comorbidities (according to ESC guidelines 2018) |

|

| nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) |

|

| intracardiac thrombus |

|

| mechanical valve |

|

| moderate to severe mitral stenosis |

|

| other valvular defects, mild to moderate |

|

| severe aortal stenosis |

|

| bioprosthetic valves (>3 months after implantation) |

|

| hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) |

|

| PTAV (percutaneous transluminal aortic valvuloplasty) TAVI (transcatheter aortic valve implantation) |

|

- trials, including the only randomized trial CADISS (Cervical Artery Dissection In Stroke, showed no difference in the risk of stroke recurrence with antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy

- if anticoagulation is indicated, warfarin should be preferred; data on the safety and efficacy of DOACs in this indication are not available

- start parenteral anticoagulation (heparin, LMWH) in the acute phase, followed by oral medications (warfarin, DOACs)

- start with LMWH in the acute phase

- then switch to DOACs or warfarin

- VTE prevention

- pulmonary embolism (PE) therapy

- effect not proven (IST trial)

- no clear indication for anticoagulation in cryptogenic stroke (incl. ESUS)

Warfarin

- based on the results of the WARSS, WASID, and ESPRIT trials, anticoagulation therapy with warfarin is not recommended in patients with a stroke of arterial origin (except for dissection and hypercoagulable states)

DOAC

-

positive results were reported in the DATAS II (Dabigatran Treatment of Acute Stroke II) trial

-

dabigatran 110/150mg vs. ASA was tested, with therapy initiated within 72h after TIA/minor stroke onset

- a phase II prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint trial

-

asymptomatic ICH 7.8 vs. 3.5% (ASA), sICH (primary endpoint) was 0% in both groups

-

while there was insufficient power to show a significant effect, there was a trend toward fewer recurrences on dabigatran according to MRI findings (6.3% vs. 9.9%)

-

Combination of DOAC + antiplatelet therapy

Low-dose rivaroxaban + ASA

- COMPASS trial

- inclusion criteria: patients with coronary artery disease who were younger than 65 years of age were also required to have documentation of atherosclerosis involving at least two vascular beds or to have at least two additional risk factors (current smoking, diabetes mellitus, an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <60 ml per minute, heart failure, or non-lacunar ischemic stroke ≥1 month earlier

- n=27,395

- primary endpoint: a combination of CV death, stroke, myocardial infarction

- rivaroxaban 2×2.5mg + ASA 100mg is superior to ASA 100mg

- primary endpoint: 4.1% vs. 5.4%

- major bleeding: 3.1% vs. 1.9% (but there was no difference in fatal and intracranial bleeding)

- mortality 3.4% vs. 4.1%

- net benefit 4.7% vs 5.9% (HR 0.8)

- rivaroxaban 2x 5mg alone is not superior to ASA (there were fewer ischemic events and more bleeding)

- WARSS trial (Warfarin Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study) compared the efficacy of warfarin with a target INR of 1.4-2.8 versus ASA at a dose of 325 mg. It involved 2206 patients with non-cardioembolic stroke. This trial did not demonstrate the superior efficacy of warfarin over aspirin in preventing stroke recurrence and death (17.8% vs. 16%). The incidence of hemorrhagic complications was also not significantly different between the two groups (2.2% warfarin vs. 1.5% aspirin). The effect was also not demonstrated in the subgroup of patients with evidence of stenosis or occlusion of a major artery

- WASID trial (Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Study) evaluated the efficacy of warfarin with a target INR of 2-3 versus aspirin in patients with angiographically proven symptomatic intracranial stenosis >50%. The study was terminated early for safety reasons due to a high incidence of bleeding complications in the anticoagulation group. The primary endpoint was achieved in approximately 22% of patients in both arms

- ESPRIT (European/Australasian Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischaemia Trial) trial compared the efficacy of warfarin with INR 2-3 (n=536) versus 30-325 mg aspirin (n=532) in secondary prevention in patients with TIA or cerebral infarction of presumed arterial origin. The primary endpoint was death from vascular causes, non-fatal stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and major bleeding complications. The mean follow-up time was 4.6 years. 19% of patients on warfarin and 18% on aspirin achieved the primary endpoint. The efficacy of anticoagulation therapy compared with aspirin in preventing ischemic events (major ischemic events 62 vs. 84) was neutralized by a higher incidence of major bleeding events (45 vs. 18)

Monitoring

Regular monitoring is crucial for patients on warfarin, using blood tests such as INR. For DOACs, routine monitoring is less stringent but still important to assess kidney function and potential drug interactions.

In a patient on anticoagulant therapy, the following at each visit:

Adherence – verify compliance + repeat education

-

- switch from warfarin to DOAC (if possible) when INR fluctuates, but good adherence is essential (missing a single dose of DOAC can have a greater impact than missing a single dose of warfarin)

- repeatedly educate the patient on the correct use of the medication

- advise the patient to carry a medication chart and anticoagulant therapy card in their pocket

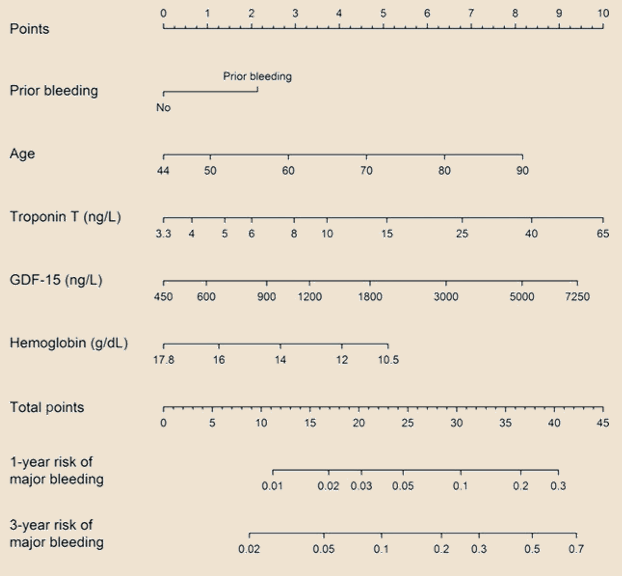

Bleeding risk assessment

-

- search for bleeding complications

- review bleeding risk scales – HAS-BLED score

- consider using PPIs if necessary

- assess the need for dose reduction or drug switching

Creatinine clearance (use the Cockcroft-Gault formula) – monitor renal function, adjust DOAC dose if needed

-

- every 12 months in healthy patients < 75 years of age

- every 6 months in patients ≥ 75 years of age or in frail individuals

- CrCl/10 determines the interval in months for patients with CrCl < 60 mL/min

Drug interaction

-

- check for potential drug interactions – may increase bleeding risk or reduce the anticoagulant effect (e.g., antirheumatic drugs, verapamil in patients on dabigatran, etc.) → see the chapter on DOACs

- check for potential drug interactions – may increase bleeding risk or reduce the anticoagulant effect (e.g., antirheumatic drugs, verapamil in patients on dabigatran, etc.) → see the chapter on DOACs

Examination and other

-

- monitor blood pressure and weight

- check for any signs of thromboembolism or bleeding

- inquire about any adverse reactions

- laboratory tests, besides CrCl, may include:

- complete blood count, renal and liver tests (at least annually, more frequently in individual cases)

- specific tests to monitor the anticoagulant effect in selected patients

Anticoagulant therapy and renal functions

- patients with renal insufficiency require special attention, and their renal function should be monitored regularly during anticoagulant therapy

- the Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) classification divides patients into five groups based on glomerular filtration rate

Warfarin

- increased risk of drug interactions

- the risk of warfarin-related nephropathy

- a type of acute kidney injury (AKI) that may be caused by excessive anticoagulation with warfarin and other anticoagulants

- other causes of AKI must be excluded

- negatively affects bone metabolism, exacerbating “adynamic bone disease” and contributing to vascular calcification

- warfarin increases the risk of calciphylaxis, a large and difficult-to-heal skin lesion

- in dialysis patients, the risk of bleeding often outweighs the benefits

- warfarin remains the first-line treatment for end‐stage renal disease; the decision to use anticoagulation must be individualized

DOAC

- clinical data for patients with CKD stages 3-4 are available

- both apixaban and rivaroxaban can be administered at a reduced doses up to a CrCl of 0.25 mL/s (15 mL/min)

- DOACs are safe and effective in these patients

- in ROCKET AF sub-analyzes, there was a reduced risk of bleeding compared to warfarin

- apixaban at the dose 2.5 and 5 mg leads less frequently to bleeding than warfarin, and the 5 mg dose is also associated with a lower thromboembolic risk and reduced mortality [Siontis, 2018]

- prefer apixaban (AHA/ASA 2021 2b/B-NR)

LMWH

- reduce the dose according to CrCl → more about LMWHs here

- the advantage of LMWHs is their predictable effect and relatively high safety

- disadvantages: higher cost, parenteral administration, and the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)

- LMWHs are safe in non-dialysis dependent CKD but remain a challenge in hemodialyzed patients

Anticoagulant therapy and malignancy

- tumors and their treatment are associated with an increased risk of both thrombosis and bleeding

- the decision to use anticoagulants in cancer patients should be highly individualized, taking into consideration the type and stage of cancer, risk of thrombosis and bleeding, patient preferences, and overall prognosis

- management of anticoagulation in patients with cancer-related stroke often requires a multidisciplinary approach

- LMWH is the optimal treatment for patients with cancer-related venous thromboembolism (VTE) and VTE prophylaxis (Mullard, 2014)

- evidence for the efficacy of long-term LMWHs in Afib patients with malignancy is lacking

- there is limited experience with DOACs in stroke prevention in patients with malignancy (as malignancy was an exclusion criterion in most trials) → see more

- some reports demonstrated the superior efficacy of DOACs compared to VKAs and LMWHs; however, a meta-analysis of randomized trials suggests a higher risk of bleeding (O´Connell, 2020)

- data analysis of the ARISTOTLE trial demonstrated superior efficacy and safety of apixaban compared to VKAs

Anticoagulant therapy and pregnancy/lactation

Pregnancy

Lactation

- LMWH is the gold standard during breastfeeding because it does not transfer easily into breastmilk

- warfarin nad UFH do not pass into breast milk and can also be safely used (AHA/ASA 2014 IIa/C)

- DOACs should be avoided as safety and efficacy in breastfeeding women have not been established