ISCHEMIC STROKE / CLASSIFICATION AND ETIOPATOGENESIS

Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS)

Updated on 24/07/2024, published on 24/05/2023

- Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS), also known as primary central nervous system vasculitis, is a rare autoimmune disease affecting exclusively the blood vessels in the brain and spinal cord

- it is characterized by inflammation of medium to small blood vessels

- vasculitis results in infarcts, sometimes combined with hemorrhages (~10%) [Calabrese, 1997]

- the duration and course of the disease can vary from relatively benign to fulminant forms with high mortality; some individuals may experience relapses or periods of disease activity, while others may achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment

- benign forms have been termed BACNS (Benign Angiopathy of CNS)

- an interdisciplinary approach to diagnosis and therapy is required, involving a rheumatologist, internist, endocrinologist, neurologist, radiologist, and pathologist)

Etiopathogenesis

- the exact cause is unclear, but cell-mediated autoimmunity is assumed

- inflammatory involvement of the vascular wall leads to the narrowing or occlusion of the arteries, often in combination with thrombosis

- it is not associated with any known infections or systemic autoimmune disorders

Epidemiology

- occurs most commonly in the 4-6th decade of life; however, cases have been reported as young as 7 months and as old as 78 years)

- male:female ratio is 7:3

- PACNS as a cause of stroke is very rare (< 0.2% of all strokes)

Clinical presentation

PACNS has a variable course in terms of the spectrum of symptoms, severity, and rate of progression

- course

- usually progressive with an accumulation of CNS lesions and worsening deficits

- less common is a remitting (15%) or oligosymptomatic course (benign PACNS)

- symptoms

- headache (~60%), usually chronic, progressive

- thunderclap headache is more likely to be indicative of RCVS

- encephalopathy

- altered level of consciousness (~50%)

- cognitive impairment, confusion, behavioral changes

- epileptic seizures (~15%)

- TIA/stroke with focal symptoms

- paresis, aphasia, ataxia, sensory disturbances, etc.

- visual disturbances (from nonspecific to hemianopsia)

- spinal symptoms (~5-14%) [Calabrese, 1997]

- headache (~60%), usually chronic, progressive

- PACNS has no clinical signs of involvement of other systems; if found, consider other vasculitis

- rash, purpura, arthritis (polyarteritis nodosa or Churg-Strauss)

- sinusitis, pulmonary involvement (PGA)

- oral and genital ulcerations, uveitis (Behcet’s disease)

- lymphadenopathy and arthritis (sarcoidosis)

Diagnostic evaluation

In general, PACNS is very rare and extremely difficult to diagnose. It occurs predominantly in younger patients without traditional vascular risk factors and without manifestations of systemic disease. A thorough evaluation is required, including a detailed medical history, physical examination, blood tests, brain imaging, and a cerebrospinal fluid analysis. To confirm the diagnosis, a brain biopsy should be performed.

| Diagnostic criteria [Calabrese, 1988] |

|

Laboratory tests

- ESR, CRP – mildly elevated or normal

- may be normal in PACNS; significant elevation should raise suspicion of secondary vasculitis

- CSF

- initially normal findings; in the later course, hyperproteinorachia and mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (in 80-90%), reflecting aseptic meningitis [Hajj-Ali, 2015]

- in contrast to PACNS, patients with RCVS have negative CSF findings

- sometimes positive oligoclonal bands

- no tumor cells, no evidence of bacterial or viral inflammation

- initially normal findings; in the later course, hyperproteinorachia and mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (in 80-90%), reflecting aseptic meningitis [Hajj-Ali, 2015]

- blood tests to exclude other vasculitides

- basic inflammatory parameters

- ↑CRP

- ↑ESR

- blood tests for autoimmune diseases

- complement complex (lupus)

- p-ANCA, c-ANCA

- granulomatosis with polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, inflammatory bowel disease

- anti-dsDNA (SLE)

- ANA antibodies (SLE)

- most commonly used to diagnose lupus; these antibodies can sometimes also signal other systemic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, or Sjögren’s syndrome

- ENA panel (Extractable Nuclear Antigen)

- anti-Sm

- anti-RNP

- anti-SSA, anti- SSB (Sjögren Syndrome)

- ani-Scl-70 (scleroderma)

- anti-Jo-1

- antiphospholipid antibodies (SLE)

- LA

- ACLA

- anti-β2-glycoprotein I (anti-β2GPI)

- RF (rheumatoid factor)

- used to diagnose rheumatoid arthritis

- normal ranges: < 15 IU/mL, < 1:80 for titer levels

- routine blood tests

- basic metabolic panel

- to assess problems with the pancreas, liver, heart, or kidneys

- complete blood count (CBC)

- normochromic anemia, leukocytosis, eosinophilia

- coagulation studies

- basic metabolic panel

- CSF examination

- abnormal in up to 95%

- pleocytosis (less commonly mild mononuclear pleocytosis)

- proteinorhachia (~50-80%)

- oligoclonal bands (OCB); positive in (~50% of cases

- consider testing for autoimmune and paraneoplastic encephalitis antibodies

- basic infectious disease screening (Lyme disease, herpes viruses, HIV, syphilis)

The normal ESR ranges

- 0-15 mm/h for men < 50

- 0-20 mm/h for men > 50

- 0-20 mm/h for women <50

- 0-30 mm/h for women > 50

- 0-10 mm/h for children

- 0-2 mm/h for infants

CRP ranges

- < 0.3 mg/dL – normal, which is the level for most healthy adults

- 0.3-1 mg/dL – normal or mild elevation can be seen with obesity, pregnancy, depression, diabetes, common cold, gingivitis, periodontitis, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and genetic polymorphisms

- 1-10 mg/dL – moderate elevation indicates systemic inflammation, such as in the case of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or other autoimmune diseases, malignancy, myocardial infarction, pancreatitis, and bronchitis

- > 10.0 mg/dL – marked elevation signals acute bacterial infection, viral infection, systemic vasculitis, and major trauma

- > 50.0 mg/dL -severe elevation may be caused by acute bacterial infections

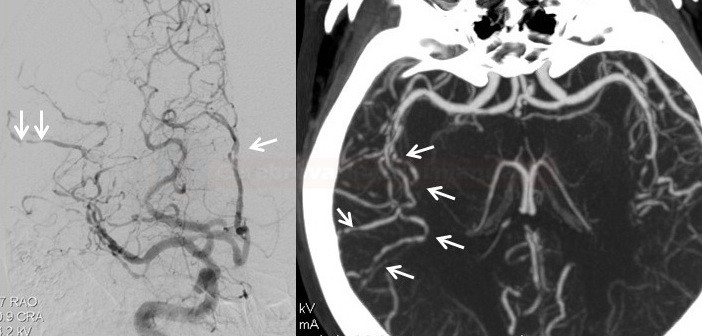

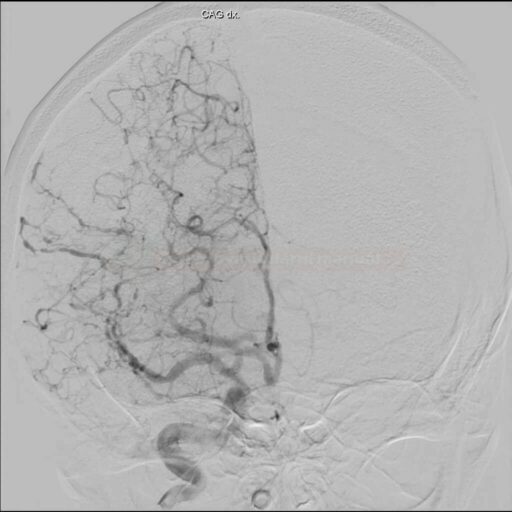

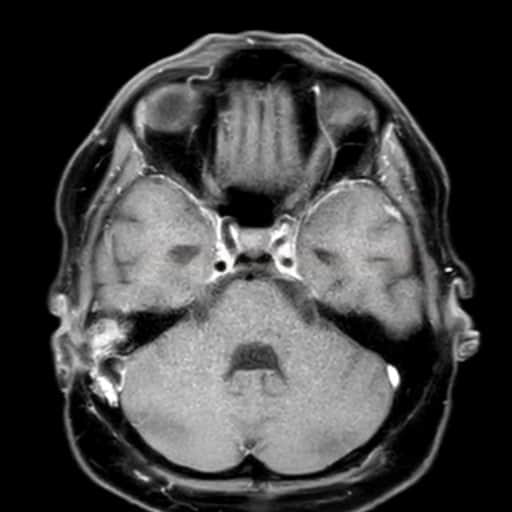

Neuroimaging

Biopsy

- a positive biopsy is the only confirmation of a “definitive” diagnosis of PACNS (in the absence of biopsy or negative findings, we can speak about “possible” CNS vasculitis)

- inconsistency between AG findings and biopsy findings is quite common; a false negative biopsy is common – due to segmental involvement, a healthy artery segment may be included [McVerry, 2017]

- a positive biopsy is described in approximately 9-36% of cases

- even with a “positive” biopsy, infection or malignancy must be excluded

- the biopsy is also of differential diagnostic importance as it allows to exclude diseases with similar clinical and radiological manifestations

- in one study, 36% of the patients had vasculitis, 25% had negative findings, and 39% had other etiologies (lymphoma, SM, infection) [Alrawi, 1999]

- according to another paper, PACNS was found in only 11% of suspected patients, and in 30%, other etiologies were found (encephalitis, lymphoma, CAA) [Torres, 2016]

- if possible, the biopsy should be taken from a lesion seen on MRI (together with leptomeninges), otherwise from the F or T lobe pole of the nondominant hemisphere

- open biopsy is more productive compared to stereotactically guided punch biopsy [Torres, 2016]

- biopsy should include a sample of dura and leptomeninges (higher detection of vascular changes), cortex, and white matter

- histological findings:

- lymphocytic infiltrates with histiocytes and plasma cells, mainly in the intima and media

- detection of large cells (giant cells) is frequent but not essential for diagnosis

- the adventitia is thickened and contains inflammatory cells that extend into the subarachnoid space

- serious complications < 4% [Torres, 2016]

Differential diagnosis

- other vasculitis (systemic diseases, parainfectious and neoplastic syndromes)

- diseases that mimic vasculitis

- reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes (RCVS)

- some other vasculopathies

| RCVS |

PACNS |

|

| gender | F > M | M > F |

| onset | sudden onset |

gradual |

| course | monophasic |

chronic with fluctuations or fulminant |

| CSF | commonly normal |

pathologic finding |

| vascular imaging |

always a pathological finding with severe vasospasms resolution within a few weeks (< 3 months) |

negative in up to 50% of cases |

| parenchymal imaging |

usually normal ICH, SAH, or edema (similar to PRES) |

multiple ischemic lesions possible leptomeningeal enhancement |

| vessel wall imaging (T1C+ dark or black blood high-res images) |

negative |

positive [Obusez, 2014] [Mandell, 2012] |

| Another vasculitis → more here |

| Malignancies |

|

| Others |

|

Management

- treatment of PACNS aims to reduce inflammation, control symptoms, and prevent long-term complications.

- a rapid decision regarding the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy in progressive forms without a definitive diagnosis of PACNS is especially challenging

- the course of the disease or treatment cannot be reliably monitored by laboratory markers

- it is difficult to distinguish permanent residual CNS damage from an ongoing inflammatory process (this may result in an erroneous escalation of immunosuppression with side effects)

- there are no randomized trials for treatment; we rely on expert consensus opinion

- glucocorticoids (GC) and immunosuppressive drugs are the mainstay of therapy

- immunosuppression puts the patient at risk of numerous complications (always carefully weigh early tapering and the true necessity of escalation)

- experience grows with additional biological therapy (rituximab, tocilizumab) in severe progressive conditions or if the first-line therapy is not tolerated

Immnusosupresive therapy

I.Remission induction

(duration 2-6 months, until clinical and radiological remission is achieved)

PREDNISONE – 1 mg/kg/day PO or IV bolus 1g/d of SOLUMEDROL (3-5 days)

CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE (CYC) – 2 mg/kg/day (max 200mg/d) nebo monthly pulses of 750 mg/m2 (for 3-6 months)

Biological therapy (can be used in case of intolerance or resistance to conventional treatment, or as combination with CYC in the severe course)

- tumor necrosis factor–α blockers

- rituximab (MABTHERA) – antibody against CD20 B-lymphocyte antigen [Patel, 2018]

- tocilizumab (ROACTEMRA) – IL-6 receptor antibody

- fewer relapses and perhaps better outcome have been described with the combination of GC+CYC [Salvarani, 2015]

- for patients with a more severe course combination therapy from the start + initial IV bolus of GC is preferred [Beuker, 2018]

- concomitant gastric protection and monitoring for adverse events are necessary

- induction of remission should last 2-4 months [Beuker, 2018]

II. Remission maintaining

- the goal is to reduce the risk of relapse

- the optimal duration of therapy is unknown, most commonly 9-18 months are reported

- de-escalation should be considered after the stabilization of clinical and radiological findings

PREDNISONE 5-20mg/day

+

- IMURAN (azathioprin) 1-2 mg/kg/day

- mycophenolate mofetil 1–2 g/day

- METOTHREXATE 20–25 mg once a week)

Standard secondary stroke prevention

- same as for other types of stroke

- antiplatelet therapy

- ASA or CLP

- no hard data on the use of DAPT

- aggressive management of vascular risk factors (statin, ACE-I, etc.)

- adequate hydration (risk of hypoperfusion, e.g., after diarrhea, febrile episodes, etc.)

- physical and occupational therapy

Interventional procedures

- little experience is available; most of the angioplasty trials had cerebral vasculitis as a contraindication

- angioplasty may be considered in a malignant course to treat the most severe symptomatic stenosis

- isolated case reports [Latacz, 2019]

- worse results compared with atherosclerotic lesions (McKenzie, 1996)

Monitoring

Monitoring of disease activity

- difficult in general as there is no specific laboratory markers of disease activity

- monitor neurostatus (new focal deficit?)

- MRI follow-up

- to exclude new, clinically silent ischemia during glucocorticosteroid tapering

- follow-up MRI no later than week 4 after initiation of therapy (within a week for more severe disease), then 3-4 months thereafter

- repeat contrast-enhanced high-resolution MRI to monitor the resolution of mural inflammation (only feasible for larger arteries – ICA and arteries of the circle of Willis)

- large and medium-sized arteries can be monitored with TCCD/MRA/CTA (stenosis grade, new-onset stenosis, etc.)

Monitoring of immunosupressive therapy

- monitoring, prevention, and treatment of drug side effects

- CYC – frequent CBC monitoring

- steroids

- diabetes screening and management

- gastric ulcer prophylaxis

- osteoporosis prevention

- CYC – frequent CBC monitoring

- change dosage carefully (risk of premature tapering or unnecessary escalation)

- advice patients to use pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis if they are on long-term steroid therapy

Prognosis

- the prognosis of PACNS depends on the extent of CNS involvement and response to treatment

- a favorable outcome can be expected in milder cases, responding well to early and aggressive immunosuppressive therapy

- poor outcome is associated with initial extensive vascular involvement and multiple strokes and in patients not responding adequately to treatment

- rare fulminant variants are associated with high mortality

- relapses may occur after initial remission; long-term maintenance therapy and monitoring are required to prevent them

- prolonged use of steroids and immunosuppressants is associated with a significant risk of adverse events (hypertension, type 2 DM, osteoporosis, an increased risk of opportunistic infections, etc.)

FAQs

- PACNS is a rare form of vasculitis that exclusively affects the blood vessels of the central nervous system (CNS), leading to inflammation without evidence of systemic vasculitis. It can present with a wide range of neurological symptoms, depending on the size and location of the affected vessels.

- the diagnosis of PACNS is challenging and typically requires a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies (such as MRI and angiography), and histopathological confirmation through brain biopsy, which remains the gold standard. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis can support the diagnosis by indicating inflammatory changes.

- clinical manifestations of PACNS include headaches, cognitive dysfunction, focal neurological deficits, and seizures

- treatment primarily involves immunosuppressive therapy, including high-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, to reduce vessel inflammation and prevent further neurological damage

- maintenance therapy with less toxic immunosuppressants such as azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil may follow

- the treatment regimen is guided by the severity of the disease and response to therapy

- the prognosis of PACNS depends on the extent of CNS involvement and response to treatment

- early diagnosis and aggressive treatment can improve outcomes, but relapses can occur, requiring long-term maintenance therapy and monitoring

- differentiating PACNS from secondary CNS vasculitis involves clinical evaluation for systemic signs of vasculitis, serological tests to rule out systemic inflammatory or infectious conditions, and imaging studies

- secondary CNS vasculitis is associated with systemic diseases such as lupus, Sjögren’s syndrome, or infections, whereas PACNS is isolated to the CNS without systemic involvement

- challenges include the rarity of the disease, which limits widespread expertise and consensus on management; the potential for misdiagnosis, given its nonspecific symptoms and overlap with other neurological disorders; and the side effects of long-term immunosuppressive therapy