INTRACEREBRAL HEMORRHAGE

Management of intracerebral hemorrhage

Updated on 17/06/2024, published on 20/08/2023

The goal of therapy is to minimize hematoma growth and prevent secondary injury. Hematoma growth is linked to poor clinical outcomes (a 10% increase in ICH volume increases the likelihood of a 1-point increase in mRS by 16%). The INTERACT3 trial (2023) showed that timely administration of a care bundle, which included early intensive lowering of systolic blood pressure, strict glucose control, treatment of fever, and rapid reversal of abnormal coagulation, resulted in reduced disability, lower mortality rates, and improved overall quality of life

General therapy

The tabs below discuss specific issues related to the conservative treatment of ICH. Otherwise, general principles of acute stroke management and intensive care, including management of intracranial hypertension, apply.

Blood pressure management in the acute stage

- on admission, check BP every 5-10 minutes or start invasive BP monitoring

- aggressive and rapid treatment of hypertension is an essential therapeutic approach (along with correction of coagulopathy)

- high BP is associated with an increased risk of hematoma progression with worse clinical outcome

- initiating treatment within 2 hours of ICH onset and achieving the target within 1 hour may be useful to reduce the risk of hematoma expansion and improve functional outcome (AHA/ASA 2022, 2a/C-LD)

- ischemia around the hematoma plays a minor role (except perhaps in large hematomas), and BP reduction seems safe

- continue with chronic PO medications if possible; if dysphagia or decreased LOC is present, use parenteral therapy or place a nasogastric (NG) tube

- in patients with known hypertension, the target BP may be higher due to altered autoregulation with the risk of decreased CPP

- nitroprusside is not recommended due to its potential to increase intracranial pressure (ICP)

- smooth and sustained control of BP is required; avoid sudden drops or peaks in BP and maintain Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) >85 mm Hg

- if the ICP is monitored, then correct BP to maintain CPP 60-80 mm Hg

| Initial systolic blood pressure (SBP) 150-220 mm Hg in patients with ICH of mild-to-moderate severity |

|

| Initial SBP > 220 mmHg or large hematoma |

|

- the 1st line of IV drugs:

- urapidil (EBRANTIL)

- enalapril (ENAP)

- labetalol (TRANDATE)

- if they fail, try nitrates – isosorbide dinitrate (ISOKET)

- start peroral medication ASAP (e.g., via NG tube if necessary) and gradually reduce/withdraw parenteral medication

Correction of hemostasis disorders

- early detection and urgent correction of coagulopathy is a key procedure in ICH therapy

- antifibrinolytic agents are not recommended except for thrombolysis-related bleeding

Patients with normal coagulation parameters

- the FAST trial with recombinant f.VII (NOVOSEVEN) failed to show a reduction in mortality and disability (Mayer, 2008]

- reduced hematoma growth was offset by an increased risk of thromboembolic complications (especially in the 80 μg dose cohort) (AHA/ASA 2010 class III, LoE A)

- similarly, the effect of etamsylate (DICYNONE) and tranexamic acid (EXACYL) has not been demonstrated

- negative TICH-2 and STOP-AUST trials

- negative meta-analysis of 4 RCTs – hemostatic therapy showed a marginally significant benefit in reducing hematoma expansion in high-risk patients (predicted by CT scan markers). However, no significant improvement in functional outcome or reduction of mortality was observed [Nie, 2021]

- the TICH-2 trial showed no benefit even in the subgroup of patients with positive spot sign [Ovesen, 2021]

Intracerebral hemorrhage in thrombocytopenia and thrombocytopathy

- platelet administration:

- if thrombocytes are < 50 000/μL

- in patients with presumed good prognosis, consider transfusion if thrombocytes are < 75 000/μL)

- some data suggest that thrombocytopenia does not affect the rate of hematoma enlargement and functional outcome in ICH patients, either with or without antiplatelet therapy [Mrochen, 2021]

- antiplatelet monotherapy probably does not significantly increase the risk of hematoma progression [Mrochen, 2021]

- a higher risk is associated with DAPT, especially if multiple risk factors are present

- routine platelet infusion is not recommended

- the effect is not proven (PATCH trial) [Baharoglu, 2016]

- platelet transfusions are potentially harmful (AHA/ASA 2015 3/B-R)

- IV desmopressin acetate (OCTOSTIM) 0.3 μg/kg in 100 mL of NS over 15-30 minutes can be administered [Desborough, 2017]

- the effectiveness of desmopressin (with or without platelet transfusions) in reducing the expansion of the hematoma is uncertain (AHA/ASA 2022 2b/C-LD)

- some trials failed to prove the benefit [Schmidt, 2019]

- DASH trial is ongoing

- the effectiveness of desmopressin (with or without platelet transfusions) in reducing the expansion of the hematoma is uncertain (AHA/ASA 2022 2b/C-LD)

- for other thrombocytopathies, consult a hematologist

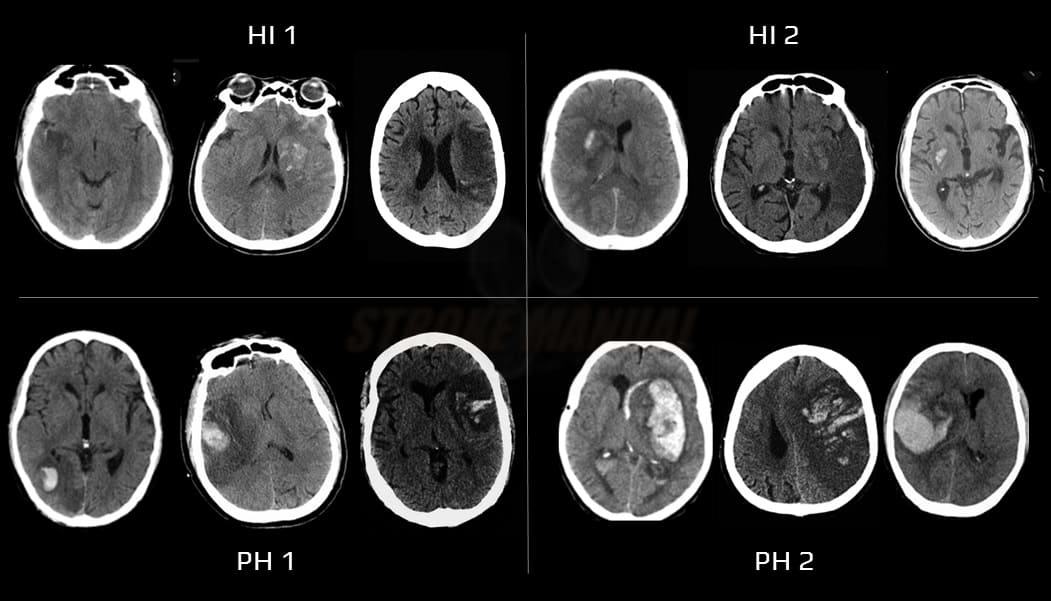

Hemorrhagic infarction, thrombolysis-related bleeding

→ bleeding complications during thrombolysis

- usually a consequence of late reperfusion with extravasation of blood into infarcted tissue (0.6-5%)

- risk factors:

- early anticoagulation (therefore not recommended)

- thrombolysis (symptomatic IC bleeding ~ 6%)

- extensive infarction

- large artery occlusion with late recanalization

- poorly controlled hypertension and hyperglycemia

- clinical presentation depends on the extent of bleeding (ECASS classification)

Intracerebral hemorrhage during anticoagulation therapy

- prolonged bleeding on anticoagulant therapy is present in ~ 36-54% of patients (warfarin > DOAC) ⇒ neutralization of the anticoagulant effect is therefore essential [Steiner, 2017]

Surgical treatment

- the goals of surgery are to:

- decrease ICP

- reduce the secondary damage from edema

- reduce the risk of herniation

- eliminate potential sources of bleeding

Monitoring of intracranial pressure (ICP) |

- ICP sensor can be implanted after correction of coagulation parameters

- indications are equivocal

- patients with GCS ≤ 8 with extensive parenchymal hematoma, intraventricular hemorrhage with obstructive hydrocephalus (AHA/ASA 2015 IIb/C)

- intraparenchymal or intraventricular sensor

- the intraventricular catheter is inserted through the brain into the lateral ventricle; it allows concurrent CSF drainage

- major risks:

- bleeding – the type of the hemorrhage depends on the site of insertion (intraparenchymal, intraventricular, or subdural)

- infection (up to 12%, the risk is higher with intraventricular catheters) – CSF should be sent for cytology and culture analysis if infection is suspected

- leave the sensor for a maximum of 5-7 days; beyond this time, the risk of infection increases, and the accuracy of the measurement decreases

- manage ICP according to head trauma protocols

- target CPP 50-70 mmHg

- target ICP < 20 mmHg

External ventricular drainage (EVD) |

- typically used for massive intraventricular hemorrhage or expanding cerebellar hematoma with acute obstructive hydrocephalus (AHA/ASA 2022 I/B-NR)

- modern catheters allow concurrent ICP monitoring

- careful monitoring of consciousness and repeated CT scans are required

Hematoma evacuation |

- relieving the pressure of the hematoma on the surrounding tissue may reduce secondary damage

- craniotomy is associated with complications, including continued bleeding

- minimally invasive surgery seems to be beneficial

- positive results of ENRICH trial (2024) with minimally invasive parafascicular surgery (MIPS) may change current practice

- urgent evacuation of ICH (< 4h) does not improve outcome or mortality and may increase the risk of bleeding (AHA/ASA 2015 IIb/A)

Indications

Surgery (12-96h from onset) indicated

- supratentorial hematoma with volume of ~ 30-60mL, localized near the brain surface + progressive alteration of LOC due to expansive hematoma

- cerebellar hematoma > 3cm (> 10-15 mL) or brainstem compression with/without obstructive hydrocephalus

- prompt surgical evacuation of hemorrhage with or without EVD is recommended over medical management alone to reduce mortality (AHA/ASA 2022 I/B-R)

- simple insertion of a ventricular catheter without simultaneous hematoma evacuation is not recommended (AHA/ASA 2015 III/C)

- ICH evacuation may be combined with treatment of the source of bleeding

- especially acute treatment of aneurysms is required (high risk of early rebleeding)

Surgery not indicated

- deep subcortical hematomas with volume ≥ 60mL and GCS ≤ 8

- high mortality ~80-90%; results of conservative and surgical treatment do not differ according to the STICH trial

- hematoma in supratentorial localization with volume < 30mL

- brainstem hematoma

- cerebellar hematoma < 3 cm in diameter without brainstem compression/hydrocephalus

- urgent surgery< 4 hours from onset of bleeding

Surgical procedures

- MIS (minimally invasive surgery) – stereotactic hematoma evacuation (with/without tPA application) (AHA/ASA 2022 2a/B-R)

- 12-72 h from the onset, GCS 5-12; hematoma volume > 20-30mL

- puncture and aspiration of hematoma to reduce the volume to < 10-15 mL, possible tPA application of 1mg every 8h or 2mg every 12h

- favorable results in phase 2 trial (mortality 7% vs. 14%) – MISTIE (Minimally Invasive Stereotactic Surgery – rt-PA for ICH Evacuation)

- positive results of the ENRICH trial (2024)

- lobar or anterior basal ganglia hemorrhage with a volume of 30-80 mL

- minimally invasive surgical removal of the hematoma plus guideline-based medical management (surgery group) versus guideline-based medical management alone (control group)

- enrolled within 24 hours

- 30-day mortality 9.3% (surgery) vs 18%

- 12-72 h from the onset, GCS 5-12; hematoma volume > 20-30mL

-

- prefer MIS over craniotomy evacuation (AHA/ASA 2022)

- osteoplastic craniotomy with hematoma evacuation +/- decompressive craniectomy

- in most patients, the usefulness of craniotomy for hemorrhage evacuation to improve functional outcomes or mortality is uncertain (AHA/ASA 2022 class 2b/A)

- in patients with supratentorial ICH who are deteriorating, craniotomy for hematoma evacuation might be considered a lifesaving procedure (AHA/ASA 2022 class 2b/C-LD)

- decompressive craniectomy (with or without hematoma evacuation) can be a lifesaving procedure in comatose patients with prominent mass effect (with midline shift) and drug-refractory IC hypertension (AHA/ASA 2022 2b/C-LD)

- not only hematoma volume but also subsequent edema formation contributes to mass effect and intracranial hypertension in ICH; perihematomal edema usually peaks around the 3rd or 4th day but has a very inhomogeneous time course and may increase up to 2 week

Treatment of the source of bleeding |

- the source of bleeding is most common in atypically localized hematomas and younger patients without hypertension

- acute intervention is indicated for aneurysms with an extremely high risk of early rebleeding

- acute management of other bleeding sources follows the general indications for surgery:

- mostly expansive hematoma, 30-60 mL, GCS > 8

- cerebellar hematoma compressing the brainstem (usually > 3 cm)

- malformations are often complicated and require a multidisciplinary approach (a combination of endovascular, surgical, and radiotherapy)

Surgery in intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) |

- treat the underlying cause of bleeding

- detect and treat possible obstructive hydrocephalus (serial neurological status examinations and repeated CT scans are required for the diagnosis)

- external ventricular drainage (EVD) may reduce mortality, especially in patients with large ICH/IVH and impaired level of consciousness (LOC) (AHA/ASA 2022 1/B-NR)

- for patients with a GCS score >3 and primary IVH or secondary IVH (with supratentorial ICH of <30-mL volume) requiring EVD, minimally invasive IVH evacuation with EVD plus thrombolytics is safe and reasonable compared with EVD alone to reduce mortality (AHA/ASA 2022 2a/B-NR)

- for patients with a GCS score >3 and primary IVH or secondary IVH (with supratentorial ICH of <30-mL volume) requiring EVD, the effectiveness of minimally invasive IVH evacuation with EVD plus the use of thrombolytics to improve functional outcomes is uncertain

- for patients with large ICH/IVH and impaired LOC, the efficacy of EVD to improve functional outcome is not well-established

- intraventricular application of tPA may facilitate the thrombus evacuation from the ventricles; it appears safe, but clinical efficacy is unclear

- CLEAR-IVH study – systemic bleeding 4%, ventriculitis 2%

- CLEAR III trial – no substantial improvement in functional outcome at mRS 3 cutoff compared to saline irrigation; mortality reduced by 10%

- intraventricular tPA protocol – 1 mg of alteplase, 8h apart; up to 12 doses

- alternative procedures: endoscopic evacuation of the hematoma with ventriculostomy, VP shunt, or lumbar drainage – benefit is unclear (AHA/ASA 2022 2b/C-LD)

- external ventricular drainage (EVD) may reduce mortality, especially in patients with large ICH/IVH and impaired level of consciousness (LOC) (AHA/ASA 2022 1/B-NR)