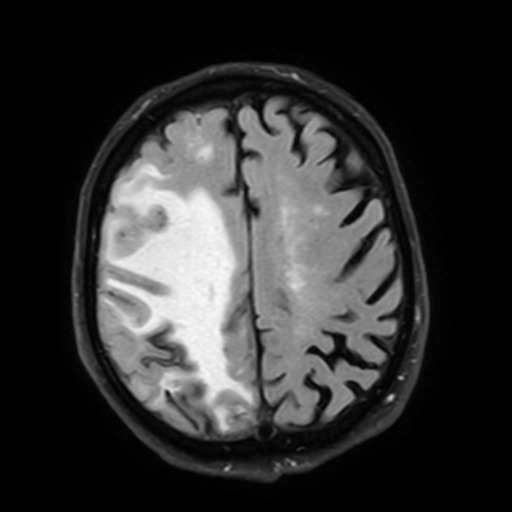

INTRACEREBRAL HEMORRHAGE

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation

Updated on 27/01/2024, published on 22/01/2024

- cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a common small vessel disease characterized by the deposition of amyloid β (Aβ) protein mainly in the media and adventitia of small- and medium-sized leptomeningeal and cortical blood vessels

- Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy-Related Inflammation (CAA-RI) is a relatively rare and aggressive variant of CAA with characteristic radiological findings (extensive, asymmetric vasogenic edema)

- because corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy can be effective, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial

Definition and etiopathogenesis

- two subtypes of CAA-RI are now recognized:

- inflammatory CAA (ICAA) – non-destructive perivascular inflammation

- amyloid β-related angiitis (ABRA) – transmural or intramural inflammation

- these two conditions cannot be differentiated based on imaging alone and share the same clinical manifestations and prognosis. These diseases probably constitute a spectrum from CAA to PACNS

- some other synonyms can be found in the literature, such as primary angiitis of the central nervous system associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral amyloid angiitis, or cerebral amyloid inflammatory vasculopathy

Clinical Presentation

- no significant gender difference

- usually older individuals (an average age of 67 at diagnosis – younger than with non-inflammatory CAA)

- clinical course

- acute or subacute, less typically chronic

- at least one of the following clinical features is required and should not be attributable to acute ICH

- headache

- altered level of consciousness

- behavioral or cognitive changes (decline)

- focal neurological deficits

- seizures

- hallucinations

Diagnostic evaluation

Neuroimaging

- parenchymal imaging

- CT – subcortical WML lesions – usually a solitary area of low density

- MRI

- T2-FLAIR – extensive asymmetric confluent white matter hyperintensities representing vasogenic edema; asymmetry should not be due to past intracerebral hemorrhage

- symmetric WMLs meet the criteria for “possible” CAA-RI

- SWI/GRE (SWI is better)

- cerebral macrobleeds (parenchymal hematoma)

- cerebral microbleeds (present in > 90% of cases)

- the distribution of CMBs does not follow the regional pattern of occipital dominance in non-inflammatory CAA

- however, some cases of pathologically confirmed CAA-RI had no CMBs on MRI (Liang, 2015)

- cortical superficial siderosis (cSS)

- T2-FLAIR – extensive asymmetric confluent white matter hyperintensities representing vasogenic edema; asymmetry should not be due to past intracerebral hemorrhage

- vascular imaging (MRA, CTA)

- in ABRA, multifocal stenoses with wall thickening/enhancement in medium-sized arteries have been observed

- angiography is unremarkable in ICAA

- vessel wall imaging (dark blood MRI)

- vessel wall enhancement is not specific to inflammation and may be seen in non-inflammatory amyloid angiopathy

Serologic and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests

- elevation of inflammatory biomarkers has been observed (CRP, ESR in 30-60% of cases)

- APOE ε4/ε4 homozygosity is significantly correlated with CAA-RI

- 76.9% of CAA-RI patients versus 5.1% in non-inflammatory CAA

- APOE ε4 probably increases Aβ deposition, has a pro-inflammatory effect, and increases the risk of vascular disease

- cases of CAA-RI patients with APOE ε2/ε2 and APOE ε2/ε3 genotypes have also been reported

- CSF analysis

- increased CSF protein

- pleocytosis (in 60% of cases)

- typically, no oligoclonal bands are detected

- anti-Aβ autoantibodies are elevated in the acute phase

- patients with CAA-RI have relatively low levels of Aβ42 and Aβ40 in the CSF

Biopsy

- the gold standard for diagnosis is autopsy or brain biopsy

- brain biopsy should be taken from an area with abnormal radiologic manifestations

- however, negative brain biopsy findings do not exclude the diagnosis of CAA-RI because of the segmental distribution of pathological changes

Diagnostic criteria

- the definitive diagnosis of CAA-RI requires histopathological confirmation

- as biopsy is invasive and carries certain risks, criteria for the diagnosis of CAA-RI have been established based on clinical and radiological data (Chung, 2009) (Auriel, 2016)

- patients with probable CAA-RI can be treated with immunosuppressive therapy empirically to avoid brain biopsy

- if there is no response to corticosteroids within 3 weeks, biopsy should be reconsidered to confirm the diagnosis

Possible diagnosis (clinicoradiological diagnostic criteria)

|

|

| Probable diagnosis |

|

| Definite diagnosis |

|

Differential diagnosis

- Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA reported in AD patients treated with amyloid-lowering therapies

- monoclonal antibodies bapineuzumab, solanezumab, and aducanumab

- usually only incidental findings on imaging or edema-related symptoms (headaches, vomiting, confusion)

- edema is related to the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier and may typically resolve over a few months

- treatment: withhold further treatment with the amyloid-lowering agent + start steroids

- infection

- progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)

- meningoencephalitis of various causes

- neurosarcoidosis

- acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

- primary CNS vasculitis

- PACNS usually occurs in younger patients (mean age, 45 years), while CAA-RI is common in older individuals

- PACNS is a more likely diagnosis when symptoms involve the spinal cord

- multiple intracranial stenoses in small and mid-size vessels

- PACNS usually occurs in younger patients (mean age, 45 years), while CAA-RI is common in older individuals

- posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES)

- similar bilateral confluent T2 WMLs, often associated with hypertension or other conditions

- usually negative GRE/SWI

- sometimes difficult to distinguish from CCA-RI; it may be necessary to observe changes during follow-up to make the correct diagnosis (⇒ progressive lesions on SWI in CAA-RI)

- neoplasms, such as metastases or lymphomas

Management

- spontaneous remissions have been documented, but the overall prognosis for most untreated patients is typically unfavorable

- high-dose corticosteroids (+/- additional immunosuppressive therapy) can improve symptoms and imaging abnormalities

- both approaches seem to have similar outcomes (Caldas, 2015)

- clinical improvement occurs within 1 or 2 weeks, followed by a regression of the inflammatory findings on MRI

- immunosuppressants may be considered in cases that do not respond adequately to glucocorticoids or to prevent relapse

- one study has shown that more patients with ABRA (33.0%) require a combination of steroids and immunosuppressants compared to patients with ICAA (12.8%) to achieve similar results (Chu, 2016)

- the most commonly used immunosuppressants include:

- cyclophosphamide

- azathioprine

- mycophenolate mofetil

- methotrexate

- immunoglobulin

- there is limited empirical data regarding the selection of medication, optimal dose, and duration of treatment; dosage regimens may be extrapolated from the management of other autoimmune diseases

- non-responders (~ 60%) progress to severe disability or death despite treatment

- relapse may occur after steroid withdrawal or during the tapering process; steroid therapy remains effective during recurrence; however, an increased presence of microbleeds may be observed on GRE/SWI sequences

- although tumors, neurosarcoidosis, Hashimoto encephalopathy, ADEM, or PACNS are unlikely to be aggravated by empirical corticosteroid use, treatment may obscure the accurate diagnosis of these conditions

- moreover, before initiating immunosuppressive treatment, it is crucial to rule out underlying infections