INTRACEREBRAL HEMORRHAGE

Diagnosis of intracerebral hemorrhage

Updated on 17/06/2024, published on 27/11/2023

- for patients presenting with stroke-like symptoms, rapid neuroimaging using CT or MRI is recommended to confirm the diagnosis of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH)

- the detection of intracerebral bleeding itself by imaging methods is easy; the diagnostic evaluation is focused on determining the underlying etiology

Physical Examination and focused history

- focused medical history (see tab below)

- quick physical examination → Early management of patients with suspected stroke

- vital signs – assess airway, breathing, circulation

- a general physical examination should focus on the head, heart, lungs, abdomen, and extremities

- a focused neurological examination + NIHSS

- assess GCS in patients with impaired level of consciousness (LOC)

- time of symptoms onset (or time patient was last seen normal)

- symptoms

- headache

- thunderclap: aneurysm, RCVS, rarely CVST

- slower onset: mass lesion, CVST, ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic transformation

- focal neurologic deficits

- seizures

- decreased level of consciousness

- headache

- vascular risk factors

- prior ICH or SAH

- hypertension

- hyperlipidemia

- diabetes

- metabolic syndrome

- imaging biomarkers (e.g., cerebral microbleeds)

- medications

- anticoagulant drugs

- thrombolytic drugs

- antiplatelet agents

- NSAIDs

- vasoconstrictors (associated with RCVS): triptans, SSRIs, decongestants, stimulants, phentermine, sympathomimetics

- antihypertensives (as a marker of chronic hypertension)

- estrogen-containing oral contraceptives (↑risk of CVST)

- cognitive impairment or dementia (possible amyloid angiopathy)

- substance use

- smoking

- alcohol use

- marijuana (associated with RCVS)

- sympathomimetic drugs (amphetamines, methamphetamines, cocaine)

- liver disease, uremia, malignancy, and hematologic disorders (→ secondary coagulopathy)

Computed tomography (CT)

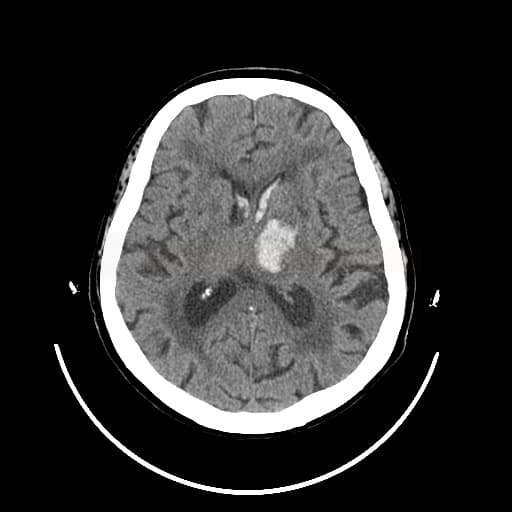

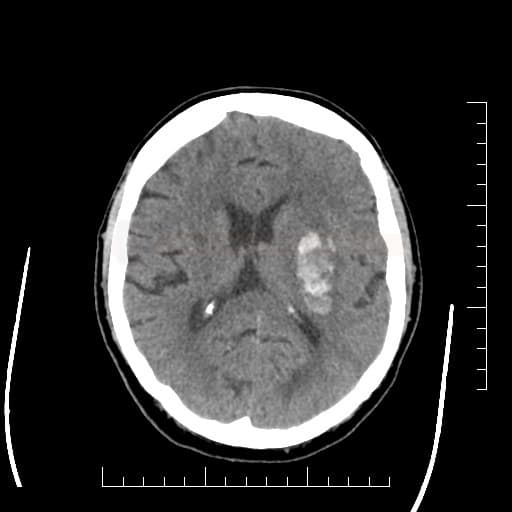

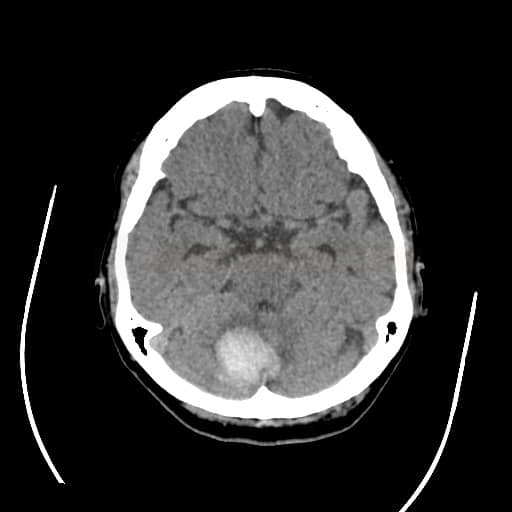

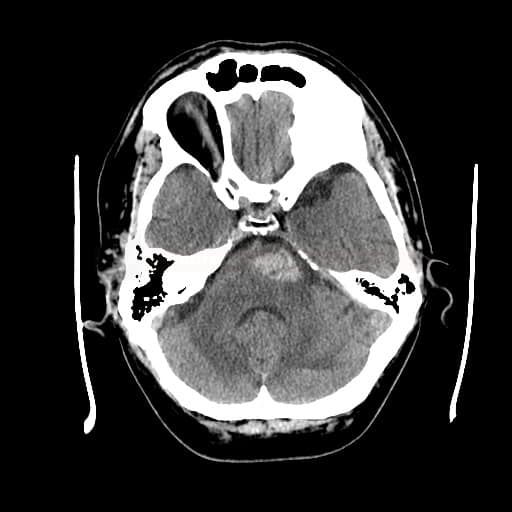

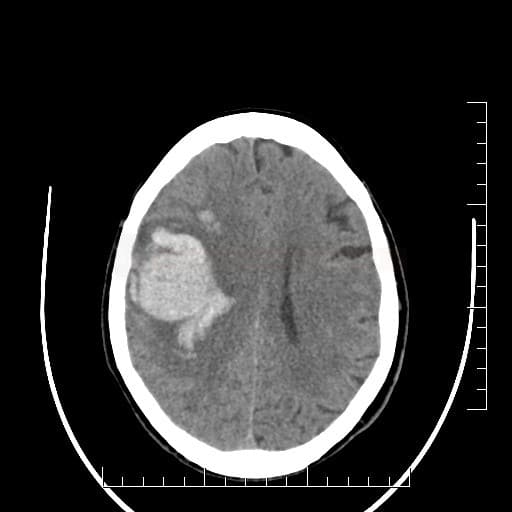

Non-contrast CT scan (NCCT)

- baseline examination objectives:

- detect and localize the hematoma

- assess its type, volume, probable etiology, risk of complications

- assess the prognosis (→ ICH scales)

- fresh blood is hyperdense on NCCT

- increased density is caused by the high hemoglobin content of retracted clot or sedimented blood

- the density of the hematoma in the acute stage is typically around 70-80HU; if the lesion has a density > 100-120HU, , it is likely to be calcification, foreign body, etc.

- resorption of the hematoma occurs within days to weeks; accompanied by a decrease in its density

- hematoma becomes isodense within 1-6 weeks

- in the chronic stage, a hypodense pseudocyst with atrophy of the surrounding brain tissue is usually found at the site of the resorbed hematoma (indistinguishable from old ischemia)

- increased density is caused by the high hemoglobin content of retracted clot or sedimented blood

- vasogenic edema gradually appears around the subacute hematoma as a hypodense area

- type and location of bleeding:

- typical “hypertensive” bleeding

- atypical bleeding → search for structural cause (CTA/MRI+MRA/DSA)

- lobar hematomas

- primary intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) – exclude AVM or small aneurysm in the ventricular wall or SAH from AComA with perforation of the terminal lamina and bleeding into the third ventricle

- age < 50 years in the absence of hypertension despite typical ICH location

- large and early vasogenic edema

- lobar hematomas

- typical “hypertensive” bleeding

- there are several NCCT predictors of hematoma expansion and unfavorable outcome in acute ICH

- Satellite sign, Island sign – subtle hemorrhages near the main hematoma

[Li, 2017] [Shimoda, 2017]

- Blend sign

[Li, 2017]

- Black Hole sign

[Li, 2016]

- Satellite sign, Island sign – subtle hemorrhages near the main hematoma

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

CT angiography (CTA)

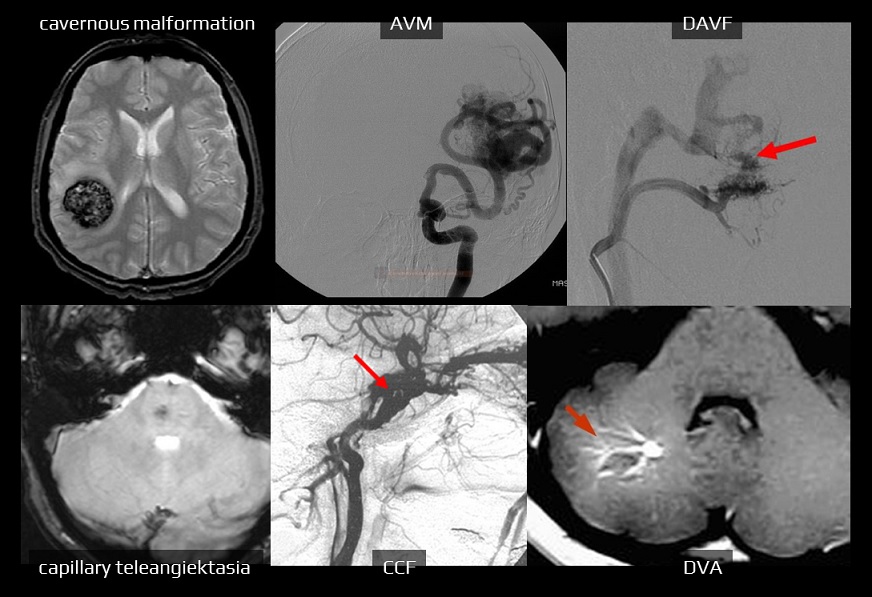

- CTA (+/- venography) is useful for the identification of the potential source of bleeding (vascular malformations) or cerebral venous thrombosis

- it can be performed as part of the baseline CT scan in patients with:

- age < 50 years

- atypical hematoma location/appearance

- hematoma in typical location without history of hypertension

- isolated intraventricular hemorrhage

- in atypical parenchymal hematomas, add MRI+MRA or DSA if baseline CTA is negative

- it may be reasonable to start with MRI and MRA to establish a non-macrovascular cause of ICH (such as CAA, deep perforating vasculopathy, cavernous malformation, or malignancy)

- MRI may help to rule out the hemorrhagic transformation of ischemia

- search for markers of hemorrhage expansion

- spot sign on source CTA images or post-contrast CT images

- prognostically unfavorable sign of ongoing bleeding and hematoma growth (Havsteen, 2014] [Sorimachi, 2013)

- accuracy of spot sign detection is high (87%); studies with hemostatic drugs in patients with positive spot sign are planned (STOP-IT, SPOTLIGHT, STOP-AUST) [Huynh, 2013]

- “leakage sign” may also serve as a predictor of continued bleeding

[Orito, 2016]

- initial CTA + delayed phase (5 min interval)

- a 10% increase in HU density indicates ongoing bleeding

- spot sign on source CTA images or post-contrast CT images

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- MRI of the brain is highly sensitive for detecting intracerebral hemorrhage

- the appearance of hemorrhage depends on the stage of hemoglobin breakdown (see table below)

- oxy-Hb is weakly diamagnetic, deoxy-Hb has 4 unpaired electrons per iron atom and is strongly paramagnetic

- gradient recalled echo (GRE) can detect early bleeding with similar sensitivity to NCCT ⇒ MRI can be used as the initial imaging method in stroke programs (Kidwell, 2004) → see here

- hyperacute hematoma:

- T1 isointense

- T2/FLAIR – isointense or slightly hyperintense

- GRE hypointense (initially only hypointense rim + core of heterogenous signal intensity due to the diamagnetic oxyhemoglobin

- DWI hyperintense, ADC hypointense

- hyperacute hematoma:

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA)

- indicated in search for the source of bleeding (consider patients’ age, clinical condition, comorbidities, prognosis, the location and extent of bleeding)

- DSA is often replaced by CTA/MRA, which can be performed quickly and without significant risk as part of the initial diagnostic workup

- DSA should be performed if CTA/MRA suggests a macrovascular cause of bleeding (AHA/ASA guidelines 2022, 1/C-LD)

- DSA confirms the diagnosis of a malformation and provides additional information about the main tributaries, presence, type, and extent of the nidus, type of flow (high or low flow), venous drainage, and other features (stenosis of a draining vein, intranidal or perinidal aneurysm, etc.)

- DSA is performed when CTA/MRA is negative or equivocal, and there is a reasonable suspicion of a bleeding source

- age < 50 years in the absence of hypertension

- atypical location or appearance of the hematoma

- typical location with no history of hypertension

- isolated intraventricular hemorrhage (AHA/ASA guidelines 2022, 1/BNR)

- in patients with spontaneous ICH and a negative DSA and no clear microvascular diagnosis or other structural lesions, it may be reasonable to repeat DSA 3-6 months after ICH to identify a previously obscured vascular lesion

Other examinations and tests

Blood tests

- complete blood count (check platelets)

- admission anemia is associated with hemorrhagic expansion and poor outcome

- thrombocytopenia is associated with increased mortality

- coagulation tests (to exclude anticoagulant-related hemorrhage and coagulopathy from other causes)

- APTT, Quick, INR, TT, fibrinogen (especially after thrombolysis)

- ECT and Hemoclot (dabigatran)

- specific anti-Xa (xabans)

- glucose

- admission hyperglycemia is associated with unfavorable short- and long-term outcome

- urea nitrogen, osmolality

- liver tests (coagulopathy secondary to liver failure)

- ionogram including Ca2+, Mg2+

- creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

- renal failure on admission is associated with poor functional outcome

- possible altered clearance of DOACs

- D-dimers

- cardiac enzymes + troponin

- inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) – infective endocarditis?

- urine toxicology screen (sympathomimetic drugs are associated with ICH)

- pregnancy test in a woman of childbearing potential (exclude peripartum angiopathy, eclampsia, HELLP syndrome, and cerebral sinus thrombosis)

Others

- 12-lead ECG on admission, followed by continuous ECG monitoring

- pulse oximetry

- blood pressure monitoring (invasive/noninvasive)

- chest x-ray