SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

Management of subarachnoid hemorrhage

Updated on 29/04/2024, published on 01/04/2023

Standard management of SAH focuses on:

- general care of acutely ill patients (incl. strict blood pressure control and maintenance of normovolemia)

- prevention and treatment of vasospasms

- detection and elimination of the aneurysm from the circulation

- prevention and management of complications (intra- and extracerebral)

General management of SAH and rebleeding prevention are discussed here; vasospasms and complications are covered in separate chapters

General therapy and patient monitoring

- patients with SAH should be promptly transferred to a center with a multidisciplinary team available 24/7 (neurologist, neurosurgeon, interventional neuroradiologist, neuro-intensivist, rehabilitation physician, neuropsychologist, and dedicated nursing staff)

- during the first 2 weeks, patients should be managed in an intensive or medium care unit

- the initial management is directed toward stabilizing the patient and selecting individuals who require urgent intervention due to complications (brain shift, hydrocephalus, etc.)

- perform a basic neurological examination, assess the level of consciousness (LOC), airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs)

- endotracheal intubation should be performed in patients presenting with coma, decreased level of consciousness, inability to protect the airway, or increased intracranial pressure (ICP)

- patients with signs of increased ICP or herniation should be hyperventilated (target pCO2 of 30-35 mm Hg)

- while there are some specifics in the conservative treatment of SAH (see tabs), the principles of general stroke management and management of intracranial hypertension apply

Laboratory studies and other methods

- serum chemistry panel – a baseline for detecting future complications

- natremia should be checked repeatedly

- CBC – evaluates potential infection or hematologic abnormalities

- prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) to rule out coagulopathy

- blood typing/screening – to be ready for potential transfusion

- cardiac enzymes, cardiac troponin

- to exclude possible myocardial ischemia

- predictor of pulmonary and cardiac complications

- a correlation was found between troponin levels and neurological complications and outcome

- arterial blood gas (ABG) – required in respiratory-compromised patients

- a baseline chest X-ray

- ECG + ECG monitoring, transthoracic echocardiogram

- differentiate myocardial ischemia from common benign changes

- patients with SAH can experience myocardial ischemia due to the increased level of circulating catecholamines or autonomic stimulation from the brain

- nonspecific ST and T wave changes

- decreased PR intervals

- prolonged QRS intervals

- prolonged QT intervals

- presence of U waves

- arrhythmias – premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), and bradyarrhythmias

Rebleeding prevention – timing

- rebleeding prevention is essential in SAH management – the risk is highest in the first few days (4% within the first 24 h) and decreases over time

- risk factors for rebleeding:

- decompensated hypertension

- aneurysm size and shape

- the severity of initial bleeding, incl. ICH or IVH

- seizures

- the most effective prevention is to treat the source ASAP (acute procedure, ideally within 24 hours) if the clinical condition of the patient permits

- thanks to vasospasm monitoring by TCD/TCCD, surgery can be performed even after 72 hours in the absence of spasm

- endovascular treatment is possible even in the presence of vasospasm (and can be combined with PTA/vasodilatation)

- early intervention allows subsequent full conservative therapy to prevent cerebral vasospasms

- indication for urgent neurosurgery:

- acute hydrocephalus requiring EVD

- life-threatening ICH (hematoma evacuation + aneurysm clipping)

- deferred management (elective procedures) should be chosen in the following cases:

- presence of vasospasms when clipping is indicated

- severe patient condition (Hunt-Hess IV-V, severe comorbidities)

- difficult, complex aneurysm

- incomplete endovascular team (e.g., at night)

- aneurysms where parent artery occlusion is considered

- it is optimal to verify collateral circulation by balloon occlusion test (BTO). However, due to heparin use, it is not suitable for the acute stage of bleeding

| Hunt-Hess score | |

| I-III | indication for acute intervention |

| IV-V | the procedure is indicated in the presence of an expanding hematoma; otherwise, the indication is uncertain (the outcome of acutely operated and non-operated patients does not differ significantly) |

Rebleeding prevention – methods

- a multidisciplinary team should be involved in decision-making (neurosurgeon, neuroradiologist, neurologist, and anesthesiologist)

- treatment method is always individualized and depends on many factors, such as:

- age and comorbidities

- Hunt and Hess (H+H) score

- the time interval since the SAH

- aneurysm size, shape, and location

- condition of the extra- and intracranial cerebral vessels (access route)

- presence of an expanding hematoma

- in general, for aneurysms that can be treated by either method, coiling is often the appropriate solution (AHA/ASA 2009 I/B)

- indications for endovascular procedure

- posterior circulation aneurysms

- anterior circulation aneurysms in elderly patients (aged > 65 years)

- patients in poor clinical condition with high surgical risk and/or cerebral edema

- patients with a high risk of vasospasms or with already developed vasospasm(s)

- cases involving multiple aneurysms where it is unclear which aneurysm is the source of bleeding and clipping would require a bilateral craniotomy

- patients with moyamoya

- patients who have failed neurosurgical treatment

- indications for neurosurgery:

- aneurysms in the middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory

- wide-neck aneurysms

- patients indicated for concurrent ICH evacuation

- case where endovascular treatment is not available or has failed

- aneurysms in the middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory

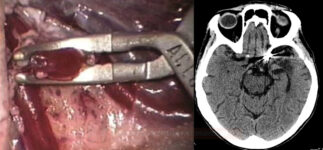

Craniotomy and aneurysm clipping |

- the advantage of clipping is the immediate and permanent removal of the aneurysm from the circulation

- some aneurysms are not treatable due to their shape/location

Endovascular procedures |

- in acute SAH, coiling alone should be performed (the use of stents and diverters requires antiplatelet therapy)

- the aneurysm sac is usually filled with detachable platinum coils that induce local thrombosis

- it takes some time for the aneurysm to be completely removed from the circulation; partial filling of the sac may occur, and repeated embolization is sometimes necessary (perform a control vascular imaging after the procedure)

- rebleeding rate is slightly higher than with clipping

- this method is preferred for aneurysms with a narrow neck (ideally < 5 mm) in the posterior circulation and for patients with more severe neurological deficits, cerebral edema, or older age with comorbidities

- the use of flow diverters, stents, or balloon-assisted coiling extends the indications for endovascular management to aneurysms with wider necks (mostly in elective procedures)

Deconstructive procedures |

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

Other surgical procedures

- management of acute hydrocephalus

- external ventricular drainage (EVD) for obstructive hydrocephalus + ICP monitoring

- lumbar CSF drainage for hyporesorptive hydrocephalus, typically for 5-7 days, with the evacuation of 100-200mL of CSF per 24h

- routine fenestration of the lamina terminalis is not indicated for reducing the rate of shunt-dependency

- management of chronic hydrocephalus (VP shunt)

- trepanation and insertion of a micro-sensor for ICP (ventricular, parenchymal) and/or tissue monitoring

- ICH evacuation (combined with clipping)

- decompressive craniectomy

- only few studies are available on decompressive surgery for the treatment of refractory increased intracranial pressure in SAH, demonstrating heterogeneous results

Predictors of shunt-dependency

- rebleeding

- vasospasms

- aneurysm in the posterior circulation or at the AComA

- IVH

- increased age

- high Fisher grade

- meningitis

- prolonged EDV

Therapy results

- effectiveness of aneurysm treatment is measured by the rebleeding rate and clinical outcome

- ISAT (The International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial) was a prospective randomized trial comparing endovascular treatment with surgical clipping

- only patients eligible for both treatments were enrolled at centers performing both treatments (n=2143)

- the primary endpoint was the prevention of disability (mRS 3-5) and death from SAH within one year after treatment

- coiling was more likely to result in independent survival at 1 year than neurosurgical clipping; the survival benefit continued for at least 7 years

- dependency or death: 23% (endovascular) vs. 30.6% (clipping), the benefit continues > 7 years

- risk of rebleeding was relatively low but more common after coiling compared to clipping – 1.6% (coiling) vs. 0.7% (clipping)

- in both groups, rebleeding occurred most frequently during the first 30 days after aneurysm treatment, and rebleeding was associated with up to 50% mortality in both groups

- CARAT (Cerebral Aneurysm Rerupture After Treatment)

- the rebleeding rate was higher in the embolized patients (3.4% vs. 1.3%)

- rebleeding in coiled patients was mostly seen in angiographically incompletely filled aneurysms

- factors leading to incomplete aneurysm occlusion are:

- larger aneurysms (> 10 mm)

- wide neck (> 4 mm)

Follow-up

- long-term follow-up is recommended (especially in patients with incomplete occlusion) → increased risk of recurrence or regrowth of the treated aneurysm or development of de novo aneurysm(s)

- in the ISAT trial, the risk of recurrent aSAH from the target aneurysms in the endovascularly treated and surgically treated groups in the first 30 days after treatment was 1.9% and 0.6%, respectively

- In the ISAT trial, the risk of recurrent SAH from the target aneurysms in the endovascularly treated and surgically treated groups at 30 days to 1 year was 0.6% and 0.4%, at 1-5 years was 0% and 0%, and at >5 years was 0.5% and 0.3%, respectively

- in the ISAT trial, the risk of recurrent aSAH from the target aneurysms in the endovascularly treated and surgically treated groups in the first 30 days after treatment was 1.9% and 0.6%, respectively

- incomplete aneurysm occlusion

- associated with a higher risk of rerupture (however, even completely obliterated aneurysms carry a risk of rerupture in the long term)

- a higher rate of incomplete occlusion is associated with coiling compared to clipping

- imaging (perioperative and long-term) is recommended to evaluate for remnants or recurrence that may require treatment

- de novo aneurysm formation

- risk is ~ 0.3% at 1-5 years, and 0.3% at >5 years

- risk factors: younger age, family history, and multiple aneurysms

- risk factors for growth and rupture of de novo aneurysms: female sex, shorter interval to formation of the de novo aneurysm, multiple aneurysms, and larger size