ADD-ONS / SCALES

TOAST classification of stroke

Updated on 22/07/2024, published on 28/12/2022

- the exact etiology of ischemic stroke has implications for both prognosis and management

- a classification system for ischemic stroke subtype, mainly based on etiology, was developed for the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST)

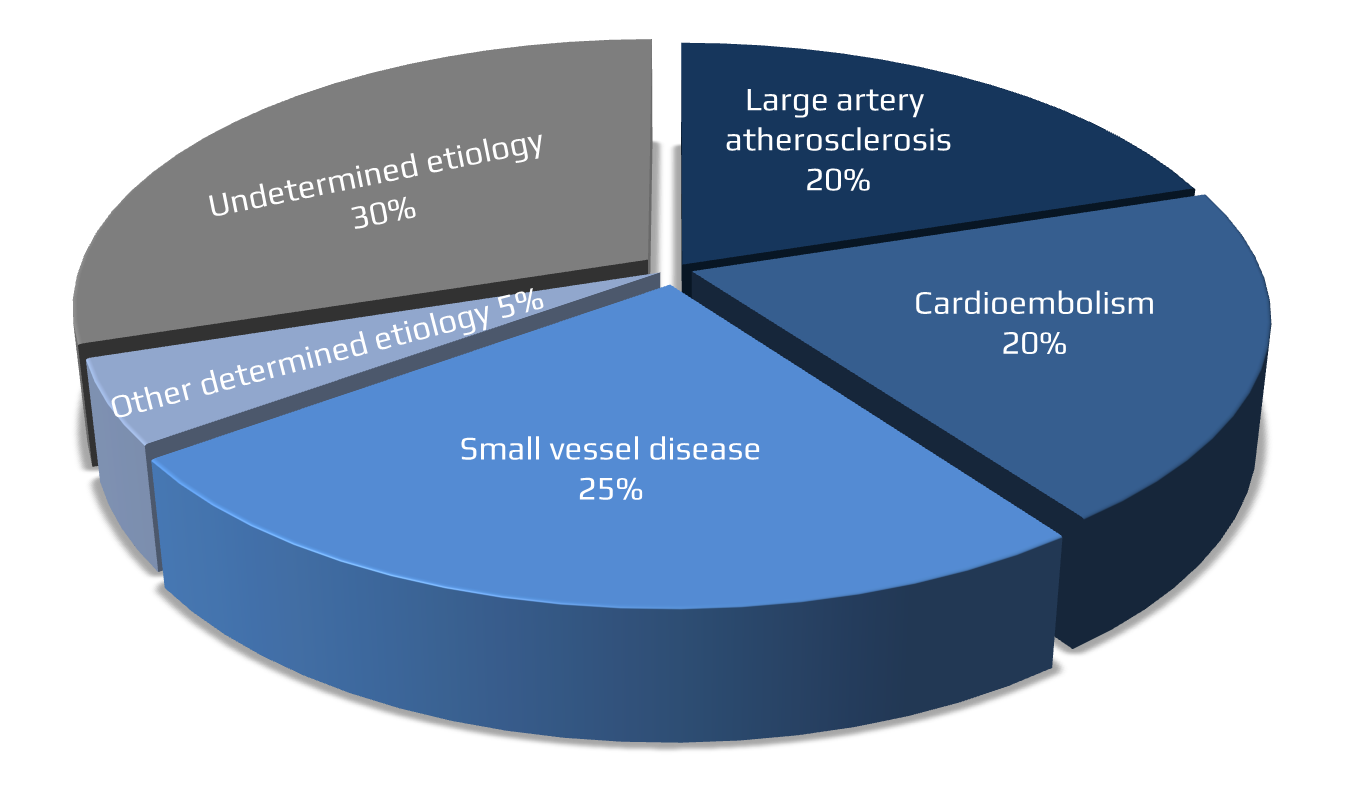

- the TOAST classification identifies five ischemic stroke subtypes:

- 1 – large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA)

- 2 – cardioembolic stroke (CE)

- 3 – small-vessel disease (SVD) / penetrating artery disease (PAD)

- 4 – stroke of other determined cause

- 5 – stroke of undetermined cause (cryptogenic stroke)

- 1 – large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA)

- diagnosis is based on clinical features and data from brain imaging (CT/MRI), vascular imaging (CTA/MRA, neurosonology, DSA), cardiac imaging, and laboratory tests

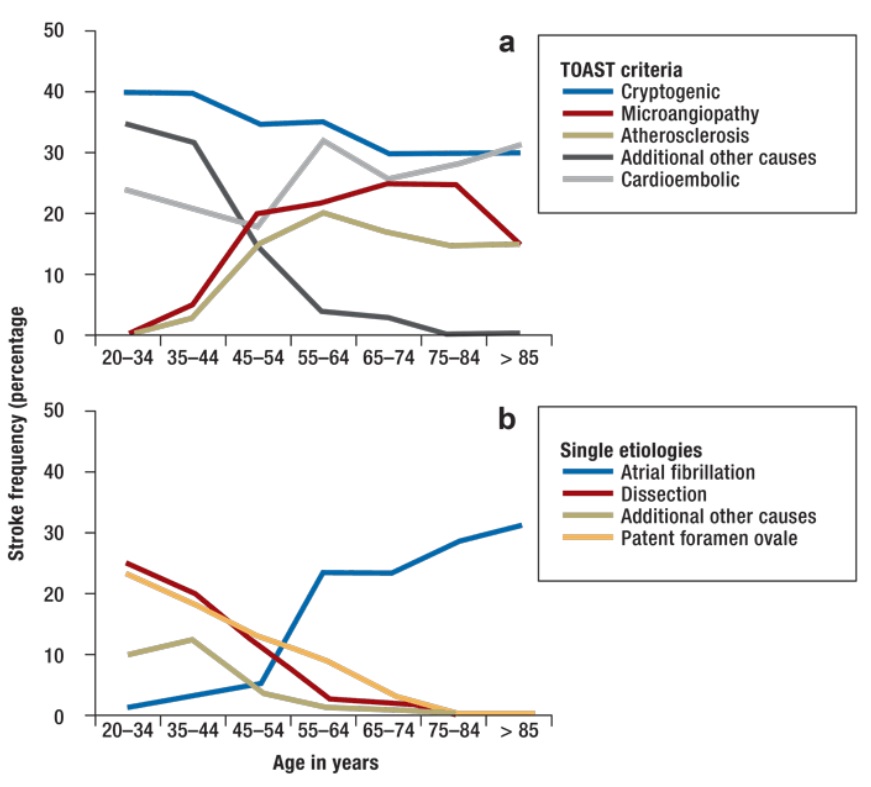

- the prevalence of each group varies depending on the mean age of the patient cohort

- cryptogenic stroke and TOAST 4 are predominant in younger age groups

- arteriolopathy and cardioembolic stroke are more prevalent in older age groups (reflecting the increased incidence of atrial fibrillation and other cardiac diseases.)

- cryptogenic stroke and TOAST 4 are predominant in younger age groups

- one large-scale application of the TOAST classification is the Get with the Guidelines-Stroke (GWTG-Stroke) registry; however, the TOAST subtypes entered into the registry were accurate in only 61% of patients (Rathburn, 2024)

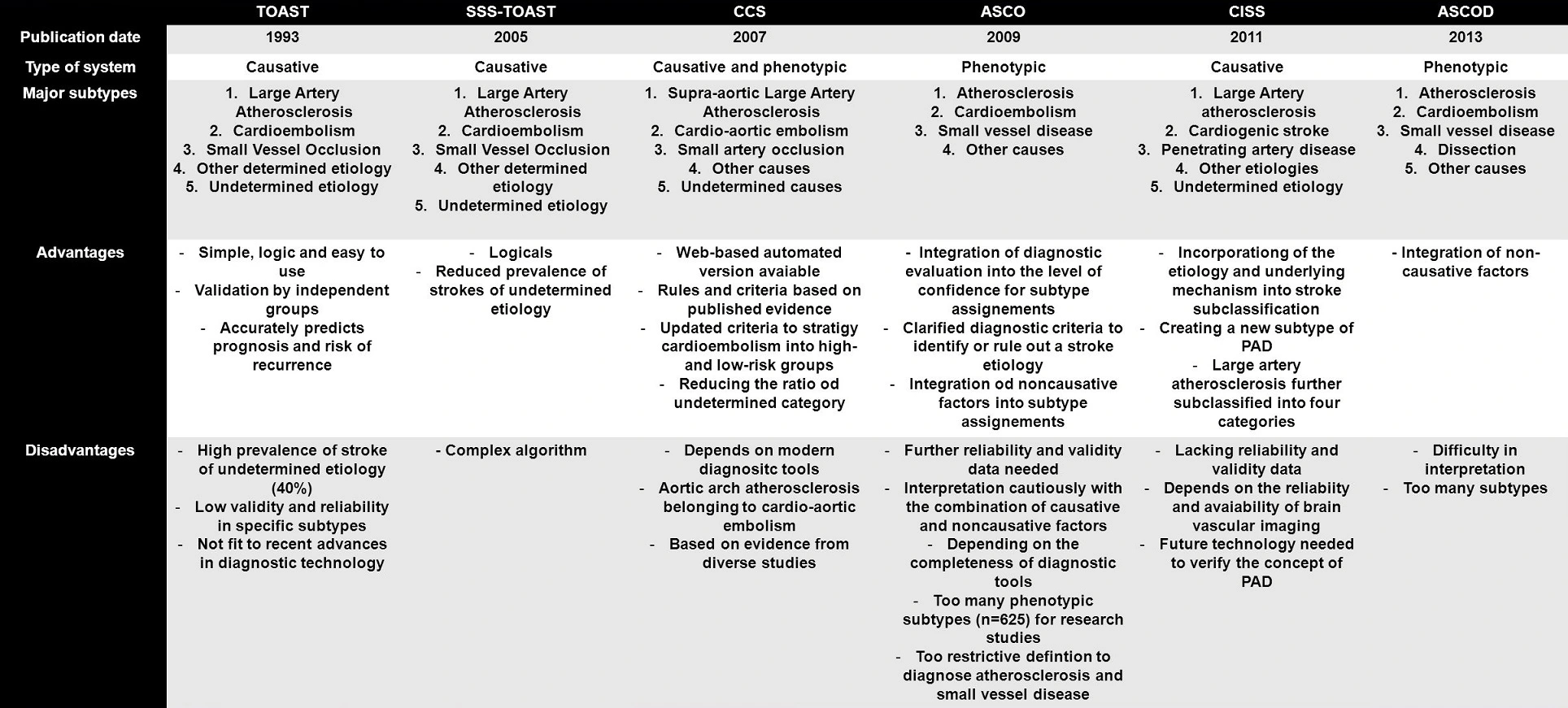

- several other improved classification systems have been introduced:

- SSS-TOAST (2005)

- CISS (2011)

- CCS (2007), ASCO (2009), ASCOD (2013)

TOAST 1 – Large Artery Atherosclerosis (macroangiopathy)

- medium and large arteries are affected

- stroke is caused by atherothrombosis or thromboembolism

- significant stenosis (> 50%) or occlusion of a relevant extra- or intracranial artery due to atherosclerosis

→ Assessment of atherosclerotic plaques

- cortical lesion on brain CT/MRI

- subcortical lesion > 1.5 cm on brain CT/MRI (originally published)

- it is known that even smaller lesions can be caused by branch artery atherosclerosis (see CISS Classification)

- it is known that even smaller lesions can be caused by branch artery atherosclerosis (see CISS Classification)

- stroke mechanisms in TOAST 1:

-

- progressive narrowing to complete arterial occlusion (symptoms vary depending on the quality of the collateral circulation)

- artery to artery embolism

- combination of both mechanisms (embolism occurring at the time of ICA occlusion)

Issues discussed regarding TOAST 1

- a specific and probably underdiagnosed cause of thromboembolism originates from unstable (complicated) non-stenosing (< 50%) plaques in CCA, ICA, aorta, and intracranial arteries [Harloff, 2010]

- additionally, small infarcts resulting from atherosclerotic plaques in the ostium of perforating arteries should be included here ⇒ branch artery disease (BAD) / branch occlusive disease (BOD)

- significance of plaque composition and morphology is increasingly acknowledged

- evidence of intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH), thrombus, thin or ruptured fibrous cap, or a large lipid-rich and/or necrotic core (visible on high-resolution MRI) correlates with an increased risk of cerebrovascular events, irrespective of stenosis severity [Kopczak, 2020] [Kamel, 2019

- these findings may support the classification of atherothrombotic etiology (TOAST 1)

- no significant atherosclerosis in major cerebral arteries

- presence of a potential cardioembolic source (especially any high-risk factor)

TOAST 2 – Cardioembolic stroke

- at least one significant potential cardioembolic source must be identified

- cardiac sources are categorized into high-risk and intermediate-risk groups based on their likelihood of causing embolization

- high-risk sources:

- clinical and neuroimaging findings are similar to those of TOAST 1

- a stroke in a patient with a medium-risk source of embolism and no other identifiable cause of stroke is classified as a possible cardioembolic stroke

- presence of significant stenosis in relevant extra- and/or intracranial arteries

TOAST 3 – Small artery disease (arteriolopathy, microangiopathy)

- lacunar strokes

- leukoaraiosis

- clinical presentation: lacunar stroke / subcortical ischemic encephalopathy

- + presence of traditional vascular risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, etc.)

- brainstem or subcortical lesion on CT/MRI (diameter < 1.5 cm)

- leukoencephalopathy on CT/MRI

(→ FAZEKAS scale, ARWMC scale)

- caused by lipohyalinosis (the main feature of lipohyalinosis is the thickening of the vessel wall with narrowing of the lumina; eventually, vessel occlusion and infarction may occur)

- distinguish non-arteriolopathic occlusion of perforating arteries

- atherosclerosis of the parent artery near the perforator origin – Branch Artery Disease (BAD) / Branch Occlusive Disease (BOD)

- infarcts tend to be larger compared to classic arteriolopathy

- high-resolution MRI can be used for diagnosis

- embolization (from proximal arterial segments or from the heart)

- atherosclerosis of the parent artery near the perforator origin – Branch Artery Disease (BAD) / Branch Occlusive Disease (BOD)

- genetic small vessel diseases should be classified as TOAST 4

- presence of significant stenosis in relevant extra- and/or intracranial arteries

- presence of a significant cardioembolic source

- hemispheric infarct on CT/MRI

TOAST 4 – Stroke of other determined etiology

- < 5% of stroke patients < 50 years of age

- mainly PACNS and Takayasu arteritis occur at a younger age

- giant cell (temporal) arteritis occurs in elderly patients (> 50 years of age)

- arterial dissection

- vasospasm

- primary (idiopathic)

- secondary (due to complicated migraine, SAH-related vasospasm, VSP provoked during angiography or by drugs, etc.)

- reversible vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS)

- moya-moya angiopathy

- multiple etiologies (e.g., idiopathic, Grange syndrome, ACTA2 mutations, vasculitis, etc.)

- metabolic diseases

- Fabry disease

- homocystinuria

- MELAS

- migraine (probably due to prolonged vasospasm)

-

heritable connective tissue disorders (HCTDs)

- Sneddon syndrome

- non-inflammatory thrombotic angiopathy affecting small to medium-sized arteries; presenting as stroke + livedo racemosa

- carotid artery web

- Grange syndrome

- dolichoectasia (usually involving the basilar artery)

- bone disorders and stroke (bony stroke)

- rare bone or cartilage anomalies affecting arteries supplying the brain

- may be considered in patients with recurrent ischemic stroke of unknown cause in the same vascular territory

- in addition to conventional vascular imaging, the dynamic imaging modalities with the patient’s head rotated or reclined may confirm the diagnosis (e.g., Bow hunter´s syndrome)

- Eagle’s syndrome is a condition associated with the elongation of the styloid process or calcification of the stylohyoid ligament, clinically characterized by throat and neck pain radiating into the ear; rarely, it may cause carotid dissection

(Ogura, 2015) (Saccomanno, 2018)

- rare bone or cartilage anomalies affecting arteries supplying the brain

- Susac syndrome (retino-cochleo-cerebral vasculopathy)

- COVID-19

- often in younger patients, in up to 1/3 of cases asymptomatic) [Shahjouei, 2021] [Fridman, 2020]

- 36% in age <55 yrs, 46% < 65 y [Shahjouei, 2021]

- predominantly embolic mechanism with large artery occlusion (LVO) due to a hypercoagulable state [Shahjouei, 2021] [Yaghi, 2020]

- more severe course compared to non-COVID patients

- ↑ D-dimers

- often in younger patients, in up to 1/3 of cases asymptomatic) [Shahjouei, 2021] [Fridman, 2020]

- hypercoagulable states

- primary – most often antiphospholipid syndrome and APC resistance

- secondary

- oncohematologic diseases (e.g., leukemia, polycythemia vera)

- thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

- non-specific intestinal inflammation

- nephrotic syndrome

- hemoglobinopathies (typically sickle cell disease)

- hematological malignancies

- hyperviscosity syndrome (HVS)

- intracardiac shunt (PFO, ASD, etc.) – usually classified as TOAST 2

- extracardiac shunt

- pulmonary AV malformations (PAVM)

- patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) (Panagopoulos, 2019)

- persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC) (Hutyra, 2010) (Azizova, 2020)

- angiography (including cardiac catheterization) → complications of endovascular procedures

- carotid revascularization (CEA, CAS)

- Extra Corporeal Circulation (ECC) related complications

- air and fat embolism (see below)

- fat embolism

- typically occurs after trauma (long bone fractures) and surgery (including plastic surgery with fat removal)

- air embolism (microscopic x macroscopic)

- a consequence of the incorrect insertion of a venous catheter into an artery [Riebau, 2004]

- improper extraction of the central venous catheter (CVC) [Brockmeyer, 2009]

- repeated IV applications in combination with pulmonary AV shunt or PFO

- during catheterization

- embolization of cholesterol particles from plaques should be assessed as TOAST 1 → Cholesterol Embolization Syndrome (CES)

- spontaneous x iatrogenic

- various mechanisms ( e.g., vasospasm, cardioembolism in endocarditis)

-

oral contraceptives (usually in combination with a hypercoagulable state and/or smoking)

-

cocaine, crack, amphetamines, LSD, and heroin (drugs often cause IC bleeding)

-

sympathomimetics, ergotamine, sumatriptan

- various mechanisms (most usually due to a hypercoagulable state or cardioembolism)

- specific causes of stroke in pregnancy:

- preeclampsia/eclampsia

- amniotic fluid embolization (AFE)

- choriocarcinoma

- postpartum cerebral angiopathy

- postpartum/peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM)

TOAST 5 – Stroke of undetermined etiology

- the cause of the stroke could not be determined with sufficient certainty

- ≥2 potential causes of stroke were identified (such as atrial fibrillation in a patient with > 50% carotid stenosis or significant carotid stenosis combined with microangiopathy)

- cryptogenic stroke (CS) – no identifiable etiology despite extensive evaluation

- incomplete diagnostic evaluation