ISCHEMIC STROKE / PREVENTION

Management of asymptomatic carotid stenosis

Updated on 07/05/2024, published on 03/01/2022

- carotid artery atherosclerotic disease (CAAD or CAD) is a substantial stroke risk factor (classified as TOAST 1)

- extracranial carotid artery stenosis is associated with ~ 20% of ischemic strokes

- classification of carotid artery disease

- asymptomatic x symptomatic (signs/symptoms of cerebral or ocular ischemia in the past 6 months)

- low risk x high risk

- high CV risk features:

- significant carotid stenosis of ≥ 50%

- detection of vulnerable plaque (characteristics are discussed below)

- additional uncontrolled CV risk factors (atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, etc.)

- identifying and treating carotid artery disease is an important part of preventing stroke

Stroke risk and prevalence of asymptomatic carotid stenosis

- the prevalence of carotid artery atherosclerotic disease depends on the population studied and the stenosis threshold used for inclusion

- the prevalence of asymptomatic stenosis > 50% is 2-8%, and the prevalence of asymptomatic stenosis > 80% is 1-2%

- the prevalence of stenosis > 50% increases with age

- < 60 years – 0.5% , > 80 years – 10%

- the risk of stroke in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis > 50% is about 1-2%/year (rate of coronary events is 7%)

- compared to symptomatic stenosis, the risk is much lower

- according to a population-based study and meta-analysis, the risk of stroke increases with the degree of stenosis – the risk of 80-99% stenosis is higher than that of 50-79% stenosis [Howard, 2021]

- see below for individual parameters of high-risk plaques

- in addition to the increased risk of stroke, patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis also have an increased risk of MI ⇒ intensive systemic therapy is essential

- in general, prophylactic CEA is not required before surgery using general anesthesia (GA) or extracorporeal circulation (ECC) → Carotid endarterectomy

Screening for asymptomatic carotid stenosis

- screening for asymptomatic carotid stenosis in the general population is not recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (due to unknown cost-benefit)

- the situation may vary from country to country.

- it is recommended to screen selected patients with:

- symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD), coronary artery disease (CAD), or atherosclerotic aortic aneurysm

- ≥ 2 of the following CV risk factors, including arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, family history of early-onset atherosclerotic disease in a first-degree relative, or family history of ischemic stroke

- symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD), coronary artery disease (CAD), or atherosclerotic aortic aneurysm

- repeated duplex examination:

- patients with carotid stenosis >50% should be assessed annually for progression and response to therapeutic intervention.

- patients with normal/mildly increased baseline IMT should not have repeat carotid Doppler (because of the very slow rate of IMT increase)

Best medical therapy

- best medical therapy (BMT) is the mainstay of carotid stenosis management (it also leads to a reduced risk of MI)

- antiplatelet drugs

- intensive management of vascular risk factors

- the relatively low risk of stroke was reported with such an approach (~1.68%/year) [Raman, 2013]

Antithrombotic therapy

Antiplatelet drugs

- aspirin 75-325 mg/d

- aspirin intolerance or contraindication: clopidogrel (75mg) or ticlopidine

- clopidogrel resistance/allergy: consider ticagrelor (BRILIQUE)

Anticoagulant drugs

- antiplatelet + low-dose anticoagulant:

- ASA + rivaroxaban 2×2.5 mg in selected patients

- in the COMPASS trial, carotid disease included both asymptomatic stenoses and patients with previous revascularization. The combination was maximally effective in patients with ‘symptomatic PAD’ defined as the co-existence of symptomatic peripheral artery disease of lower extremities and carotid artery disease

- ASA + rivaroxaban 2×2.5 mg in selected patients

- anticoagulants alone: not recommended

- antiplatelets + standard-dose anticoagulants: not recommended

Vascular risk factors management

Carotid artery revascularization

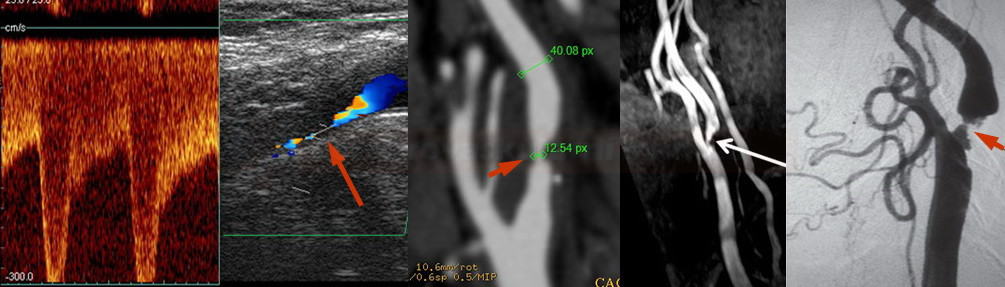

- carotid artery revascularisation (CAR) = carotid endarterectomy (CEA) or carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS)

- carotid revascularisation should only be performed in a ward with low perioperative complications (<3% for asymptomatic stenosis)

- CEA and CAS have similar safety, but CEA seems to be a little safer (ACST-2)

- the SAPPHIRE and CREST trials demonstrated the similar safety of CAS and CEA

- ACT 1 and ACST-2 trials demonstrated comparable safety even in asymptomatic stenoses [Rosenfield, 2016]

- on the other hand, CEA appears somewhat safer than CAS according to an analysis of 5 randomized trials [Moresoli, 2017]

- patients with more extensive white matter lesions on CT/MRI (ARWMC score ≥ 7) should be treated with CEA (ICSS trial)

- when considering any intervention, several aspects should be considered that may help to select patients with the highest benefit from revascularisation (→ see here)

- degree of stenosis + plaque vulnerability should be evaluated (Brinjikji, 2016)

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

All cited markers of high stroke risk associated with asymptomatic carotid stenosis:

- lack specificity

- have not been assessed in conjunction with the current optimal medical therapy

- have not been shown in randomized trials to identify those who will benefit from a carotid revascularization procedure in addition to optimal medical therapy

Stenosis degree

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

Progression over time

- risk of stenosis progression is substantial and unpredictable and increases over time

- several studies showed a higher risk of stroke in progressive stenoses > 80%

- rapidly progressive stenoses, in particular, are associated with a higher risk of ischemic stroke

- the data justify the use of serial duplex scans to follow carotid stenosis; however, there is no consensus on the appropriate intervals

- according to some recommendations, the scan should be repeated every 6-12 months for stenosis > 50% (AHA/ASA 2014 IIa/C)

Plaque morphology

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

Proof of microembolization on TCD/TCCD

- the association of embolic signals with the risk of infarction has been demonstrated in both symptomatic and asymptomatic stenoses

[Markus, 2017]

- detection of ≥ 2 embolic signals per hour indicates an unstable plaque or a plaque with concurrent thrombosis

- the annual risk of stroke risk in this condition is up to 8%

- embolic signals are more common in unstable, hypoechoic, exulcerated, poorly calcified plaques

- the use of TCD Holter may be helpful in these conditions

Evidence of silent ischemia

- some authors suggest that the incidence of silent ischemia on CT/MRI correlates with the degree of stenosis and the type of plaque (especially with exulcerated plaques)

- MRI is more sensitive than CT

- according to the ACSRS trial, the average incidence of stroke in patients with stenosis > 60% with silent ischemia is 3.6%/year compared to 1.3%/year in those without silent ischemia

- no difference was seen for stenosis < 60%

- in contrast, silent ischemia was not found to be related to stenosis severity in the ACAS trial

- although the benefit of revascularisation in patients with silent lesions has not been demonstrated in trials, their detection supports the indication for CEA/CAS in clinical practice

Impact of contralateral carotid stenosis or occlusion

| Content available only for logged-in subscribers (registration will be available soon) |

Gender

- in the ACAS trial, women had a higher surgical risk than men ( 3.6% vs. 1.7%); this has been reported in some smaller studies as well, while others have not confirmed these findings

- some advantages of CEA over CAS in women are discussed

- while there is no solid consensus, there is a tendency towards greater restraint in women when indicating revascularization

- women who undergo CEA do not need to discontinue postmenopausal HRT

Age

- CEA/CAS may not be contraindicated by advanced age alone; biological status, life expectancy, and other factors should be considered

- surgery is more common in patients < 75 years of age

- in the ACAS trial, age > 80 years was a contraindication

- in the ACST trial, the benefit was relatively small in patients > 75 years (ARR 3.3%/5 years)

- for asymptomatic stenoses, a higher mortality rate was reported in patients >75 years compared to those <75 years [Rajamani, 2013]

- in the ACAS trial, age > 80 years was a contraindication

Intracranial flow and vasomotor reactivity (CVR)

- data indicate a higher risk of stroke in patients with impaired cerebral vasomotor reactivity (VMR or CVR) and impaired intracranial flow

[Gupta, 2012]

- ~4 times higher risk of stroke/TIA (5.7% per year with an average follow-up of 24 months)

- methods used to assess CVR (VMR):

- transcranial Doppler (TCD/TCCD)

- hyperventilation/apnea test

- breath holding test

- acetazolamide (ACZ)

- hyperventilation/apnea test

- other imaging methods performed before and after administration of the vasodilatory agent (acetazolamide-challenged methods)

- MR perfusion or CT perfusion

[Kang, 2008]

- severe stenosis may sometimes manifest as false ischemic penumbra (FIP) on baseline CTP [Mosqueira, 2017]

- SPECT/PET

- MRI ASL/BOLD sequences

- MR perfusion or CT perfusion

- transcranial Doppler (TCD/TCCD)